Media Molecule’s Head of Audio, Kenny Young, gives us an insight into bringing the papercraft world of Tearaway to life with sound.

Tearaway is an adventure game exclusive to the Sony PlayStation Vita handheld system. The player is tasked with guiding their little paper messenger buddy on a mission to deliver the message that is trapped inside their envelope head by escaping the paper world and reaching the player out in the real world. 4th wall-breaking madness ensues.

Here’s a trailer to help get your head around that!

I was fortunate enough to be involved with Tearaway from its beginnings as a small team of six people working on its prototype some three years ago. This is the holy grail for interactive audio designers, analogous perhaps to having input on a film’s script albeit with regards to the experience-led rather than narrative-led games that Media Molecule makes. I knew the process would be somewhat different to how I had worked previously, but I didn’t really appreciate quite how challenging it would be…

Those of us who work in games have a massive advantage over those who work in traditional linear media – even if audio tends to be brought in later than other disciplines, the constant iteration and flux of a game during development provides opportunities for audio to influence the project in its favour, especially if your colleagues are open to it. That is the environment I’m used to working in, and over time I’ve become quite adept at joining a project at a point where it already has a good sense of its purpose and direction, and making the best use of the time I have to distill other people’s primarily non-audio-related ideas down into a sonic tapestry, an audio experience, which reflects and enhances the themes, moods and events that the game is composed from. In other words, I am a context junky – you can’t create a truly complimentary or additive audio experience without understanding the entirety of a project to its core.

If there is one thing that is missing in the early stage of a game’s development it is well-defined and reliable context, even more so when developing a new intellectual property from scratch. What context there is is shaky and fragile, it contradicts itself and is unbalanced. Your toolbox of tricks for establishing context is therefore quite useless – it’s really hard to get traction. So, there is a leap of faith required whereby you need to let go of creating anything coherent and embrace your inner incompetent audio designer – kiss goodbye to doing any work that chimes on multiple levels. It’s like being a beginner allover again, only more painful because you have the curse of knowing what it feels like to do good work.

This is nonetheless an important role even if it is utilitarian, humbling, relentless and, at times, depressing. When trying to prove features it’s important that there is something resembling a complete experience, otherwise accurate evaluation is incredibly difficult – audio can be the thing that makes a feature work or, conversely and just as important, highlights aspects of it which don’t. Clearly, there are degrees of potential sophistication and complexity here, but there is a role for audio to play even in the most basic of prototypes. However, it’s best if this is handled by someone experienced, particularly when the prototype has begun to move away from being totally bare bones – it’s not just that temp sounds (or a lack of sound) can be misleading and damaging, it’s that these early experiments have huge repercussions. Sounds thrown at a prototype by a programmer are not going to develop and improve over time which prevents a more sophisticated audio aesthetic from emerging. It’s also far less likely that anyone will spot a credible opportunity for audio and exploit it at a point where this kind of experimentation and exploration is possible. This is a serious handicap – if audio stagnates whilst art, design and technology are pulling together their direction, ideas and tools for the remainder of the project then the end result is obviously going to be somewhat lacking in comparison.

This is what pre-production is for. It doesn’t give you any longer to create the content that will ship with the game – the vast majority of the sound and music will still be conceived, recorded and implemented in the last six to twelve months – what it gives you is the opportunity to make even better use of this critical time at the end of a project. You’re already up to speed and ready to rock – you go into it knowing what it is that you and your team need to do. And, yes, you are able to influence the project in its early stages so that any audio ideas, be they the team’s or your own, have had the time and support they need to come to fruition with the best chance of success.

Although the disparity between what I was used to and where I found myself created some initial difficulty, I learnt to embrace this uncertainty once I realised it was a necessary evil that gave way to progress. Whilst you are merrily throwing shit at the wall, occasionally something will stick and sparkle. It might be the way a particular sound chimes with the visuals or makes an action or event more pleasurable to experience, or the feeling that you’ve just joined the dots between what were two previously unrelated ideas. Whatever it is, you need to build on it, hone it and exploit it. Maybe that means doing more of the same in different contexts to see if you’ve stumbled upon something that gels and unifies the audio approach, maybe that means mocking up an idea to help convince yourself of its worth or to sell it to the team (audio can massively benefit from concept art too!), or maybe that means lending some audio-backup to someone else’s idea because you see the potential in it and want to help make it happen. These epiphanies and opportunities arise at every stage of a game’s development, so this is actually pretty good general advice, but in the early phases they are rarer and more precious and so need more pro-active nurturing. Eventually, after a lot of dead-ends, you create enough dirt for the next layer of moss to grow on…

In pre-production, even more so than in full-on green-lit development, you need to provide more than just a supporting role – you need to follow your nose, go down a few of your own rabbit holes and champion those ideas that excite you otherwise you will become lost and miss out on opportunities for audio to take the lead.

The record scratching motif encountered in one of the early levels in Tearaway is a good example of a super-simple idea that’s really easy to get your head around – touch the record to make the music stop, scratch the record to scratch the music and have fun doing so. Everyone loved the idea, naturally. But it’s actually a deceptively hard trick to pull off and would have withered and died without support from me and Tearaway’s audio coder, Matt Willis. If I’m being honest, I was pretty skeptical at first because I knew how hard it would be to pull off, but it was also really attractive because making an audio-centric feature a core part of the gameplay is a great opportunity.

The basic technical problem to address is that it’s tricky to play streaming audio backwards, and backwards playback is a pre-requisite for scratching the music. It’s difficult with lossy audio formats because they aren’t designed with bidirectional playback in mind, and it can be difficult with streaming uncompressed audio because of bandwidth bottlenecks. But it can be done fairly easily with a memory-resident uncompressed sample. So, we started out with a short memory-resident music loop which we knew was going to work on a technical level but that we didn’t think would have legs because the music would be really repetitive and annoying as a result of this limitation.

The interesting discovery was that even though it worked, it sounded nothing like record scratching! I cruelly blamed this on Matt’s implementation (it was especially glitchy and digital sounding at this point!) but that was a red herring. When I researched further into real record scratching I learnt that the sound you are working with on the record (its transients and frequency components) are actually the most important consideration – you can’t just scratch anything and have it sound cool like it does in your head. This was a real breakthrough – it meant that there was little point in trying to allow players to “accurately” scratch a piece of music if when they did so it sounded weak. This wasn’t a deep feature which players would be spending hours with and improving their skill at, this was just one small moment in the game that needed to make players feel powerful. It needed to intrinsically sound and feel good.

So, we came up with an implementation whereby when the player touches a record we fade out the streaming music (actually, we quickly slow it down so that it sounds like it has come to a halt) and switch to a memory-resident sample loop. My job then became coming up with a loop which sounded good when scratched – I settled on a four bar loop of the final music track in this scene (so it sounded at least somewhat related to what the player had just been hearing), but with a recreation of the classic Fab 5 Freddy “Ah, this stuff is really fresh” sample mixed on top (the Tearaway version has me saying “Ah, this world is really papery” through a vocoder)!

There are further subtleties, such as the streaming music not actually stopping/pausing but continuing to play in silence so that when the player releases the record the music picks up from where it would have been thus making the player’s performance sound more musical, and I tweaked the speed of sample playback to feel good rather than be realistic (originally it matched the travel of a 33 1/3 LP in world space, which was neat but kinda meaningless!). We would have liked to have improved it further by making it more responsive, maybe adding in the effect of an RIAA EQ curve, but it was fit for purpose and this little feature had sucked up quite a lot of time as it is.

It was actually pretty tricky to integrate the feature into the gameplay of the level, but we persevered with this too and I’m glad it made it into the finished game – it’s just one of several 4th-wall breaking audio features in Tearaway.

Rex Crowle, Tearaway’s creative director, when faced with an early prototype Vita unit and its unique rear touch pad, had the simple idea of sticking your fingers up into the world you were holding in your hands. This core interaction is also what led him towards a papercraft world – it needed to be constructed from something tactile that your fingers could easily interact with and rip through.

So, the notion of the world needing to sound “papery” was an obvious requirement from the get-go and provided a starting point. However, this proved to be tricky – despite the game looking fairly papery from very early on there were actually very few opportunities for papery sounds due to the game being rather static and lifeless for much of its early prototype phase. Paper isn’t just a look, it’s a material – it needs to bend, unravel, wibble, fold, rip and tear if you want to introduce any of its sonic elements. It would have been easy to crowbar abstract papery sounds in there at the team’s behest, but contributing towards a non-existent game (the one people think they are making) rather than the one you actually have in front of you is a false economy. In my experience it’s always more productive to try and help solve an underlying problem than it is to use audio to mask one of its symptoms. So, I put together a video explaining the dichotomy I was being forced to face:

I think this is a good example of the perspective that an audio designer has (or should have in order to do their job well) being beneficial for a project beyond the remit of audio. I’m sure my colleagues would have reached this conclusion eventually anyway, but I’d like to think I helped force the issue a little sooner.

The paperyness of Tearaway, and opportunities for papery sounds, flourished when our graphics coder, Mark Zarb-Adami, came onboard and created the papercraft engine that allowed our designers and artists to build the game’s world out of virtual paper. Giving the designers the ability to create paper sheets of any shape and size, and have it move at any speed in a number of different ways (fold, bend, tear etc.), and all potentially under the player’s control, immediately ruled out relying exclusively on bespoke one-shot sounds to score each and every papery movement in the game – dynamic interaction requires a dynamic sound system.

Initially, we worked on the assumption that there would only be the odd bit of moving paper here and there in the world, largely because this is how the new tech was being used. So, we had a one-size-fits-all sound event which reacted dynamically to the width, speed of movement and “percentage completion through movement” of the paper sheets, the thinking being that this would cover the vast majority of subtle/generic papery movements in the game and we could then spend our time creating bespoke sounds for the set-pieces that really called for it.

A solution that is required to cope with many different (and often conflicting) contexts always tests your naïve assumptions about sound. In this case the one that really caught my attention was the relationship between the speed of movement and the relative volume of the sound. In this primitive model, it made sense to me that slow moving pieces of paper should be quieter than fast moving ones – there’s more energy required for those higher speeds after all – but once I heard this working in the game it felt quite wrong! It turned out that the designers were tending to use faster movements for more subtle and “unimportant” events (e.g. a blade of tall grass twitching around at the edge of a scene) and slower movements for more important events (e.g. a curl of paper unravelling to form a bridge for the player to cross), the slower speed being used as a way to emphasise the significance and purpose of the event. This was further exacerbated by the phenomenon of fast movements being better at catching the eye and slow movements needing more help from sound in order to catch the player’s attention. As always, the expected behaviour of sound is not always aligned with its role in an entertainment or dramatic experience.

After working through these kinds of issues, we ended up with a robust implementation solution for our papery movements, but it was pretty clear that expecting this one sound event to score everything was optimistic at best. As time went on, and the designers’ and artists’ understanding and confidence in using the virtual paper tech grew, the world of Tearaway became more animated and complex. Hearing that one papery sound everywhere just didn’t cut it, so we kept the implementation we had devised but made it so that any new objects added to the world would default to this basic paper sound whilst also adding the ability to swap it for a bespoke sound if required, thus getting the best of both worlds.

This flexibility, alongside a general trend in the game for bespoke content (i.e. not relying upon a reusable library or template but making almost everything you see from scratch) increased the requirement for just the right kind of papery sounds to fit the movement and moment.

I’m a big fan of working intuitively, in the moment, and taking advantage of inspiration when it strikes so as to stay true to an idea. One of the ways I encourage this in my workspace, and in the edit suites of everyone on my team, is to have a microphone permanently set up and ready to go. Our rooms are acoustically treated, and fairly dead, but everyone also has a couple of free-standing acoustic baffles to further improve recording quality. In a soundscape which features paper so prominently, we clearly weren’t going to be relying on library sounds when paper is such an easy material to access, record and perform with. This was true to such an extent that I can’t say I ever re-used any of the paper sounds I had previously recorded – it was always easier to have a supply of paper to hand and knock something out there and then.

I applied the same run and gun approach to the music on Tearaway – most of the music I wrote was done in a fairly quick and dirty fashion as a direct response to the game rather than passing through a long thought-process or heavy iteration cycle – I’d play the game or watch a cutscene, grab an instrument and get it down. This was also one of the top priorities when finding another composer to work with – I settled on Brian D’Oliveira in part because he was a multi-instrumentalist who was more than happy to get his hands dirty and could turn around great results in a very short space of time.

This approach isn’t about convenience, it’s absolutely essential when trying to make best use of the limited amount of “oh crap, we’re actually finishing this thing” time at the end of a project. One advantage I have is that Media Molecule’s games have a hand-made visual aesthetic that not only permits but actually requires a naïve, hand-made audio aesthetic. Another I had on Tearaway was my aforementioned involvement with the project from its inception which facilitated quick decision-making and strong direction. The main disadvantage I have is that the team really take it to the wire on every project in the pursuit of quality – I know all game teams encounter this last-minute chaos to a certain extent but at Mm it’s a bit of a party trick now to remake the majority of the level content in the last three months. The only way I’m able to keep up and deliver is by ensuring that my team is composed of audio ninjas, and having supportive colleagues who understand the audio team’s requirements.

Siobhan Reddy, our Studio Director and head of production, always made sure I was present in meetings and up to date on the latest goings on in the project, gave the audio team an extra couple of weeks on top of the art and design team to finish our work to the required standard, and sanctioned my desire to have all the content team’s changes and fixes buddy-checked by a member of the audio team in the last couple of weeks so as to catch the inevitable audio content rot. Our lead coder, Chris Cummings, gave us an extra couple of megs memory in the last few weeks so that we didn’t have to compromise the audio experience when fixing some out-of-memory audio crashes. And the level designers were supportive of changes that allowed sound and music to be presented as best it could, allowing the audio to lead the experience at times. These are just a few of the contributions that non-audio members of the Mm team made towards Tearaway’s audio experience.

Games are made by teams, and the relationship between the audio team and everyone else is far more important than any piece of technology. Interactive audio toolsets increasingly deliver on the promise of empowering the autonomous audio designer, but this is a double-edged sword. On the one hand it opens the flood gates for experimentation and investigations without the bottleneck of “other people” getting in the way. But on the other hand it further enables and permits the entrenched “make do and mend” attitude adopted by or ingrained into many audio folk (the aforementioned use of audio to wallpaper over cracks rather than addressing underlying problems) – this is a step backwards and does nothing to address the ghettoisation of audio. Always be conscious of the impact your tools have on your processes and workflow – master the tools, don’t let them master you.

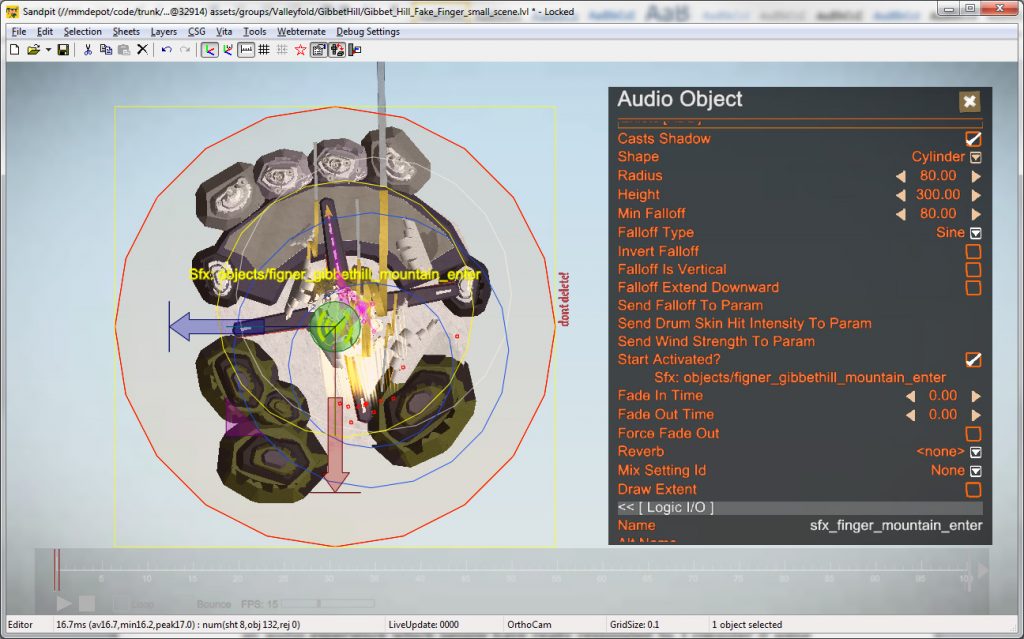

The vast majority of audio implementation in Tearaway – everything apart from animation and hard-coded audio events such as UI and gameplay sounds – was done in the same proprietary level editor that the designers and artists were working in. We had a fairly straight-forward audio object (sphere/cylinder/cuboid/polygon) collision-based implementation for both sound and music, but when combined with the level editor’s logic scripting system and a bunch of exposed parameters that we were able to tie into we had a really powerful suite of tools that allowed us to indulge in some fairly esoteric implementations and attention to detail. Props to Ed Hargrave and Todd Baker who helped me finish off the project and, in addition to creating most of the beautiful level ambiences and spots, added a lot of the nice subtleties and polish that really helped bring the world to life through sound, be that the dynamic wind model in the game controlling the sound of the wind breezing through the grass your messenger is standing in, or the tiny little sound a bent piece of paper makes when your messenger walks onto it and it makes contact with the sheet below.

It’s all of these hundreds of little details and ideas that have added up to create an audio experience which people have really responded to. I consider it some measure of success to have any aspect of the audio in a project picked up on by critics and fans, which usually just translates to a few shout outs for the music. But I’m really proud that the sound in Tearaway has caught people’s attention, particularly its role in making the world feel tactile and responsive, and lulling players into feeling like they really are holding a world made of paper in their hands.

You can follow Kenny on Twitter @kcmyoung

—

Copyright © 2013 Kenneth C M Young

So much goodness here Kenny. Wonderful glimpse into the worlde of Mm production. SO many key things to take away (for me) here that you’ve captured so well with great examples…

…some Tearaway Takeaways… (sorry!)

Pre-production is a completely different audio mindset than any other kind of audio production.

DIrty, fast, context-less, fragile, unbalanced and contradictory – “utilitarian, humbling, relentless and, at times, depressing” – These are all incredibly valuable states to be in to learn and to make mistakes. I can’t think of a better term than ‘humbling’, it goes directly to the core of the process and mindset of beginning to build something together with a team. It is really important to emphasize that pre-pro is a completely different ‘job’ to that which most people think of as ‘audio designers’ doing.

Working intuitively.

“involvement with the project from its inception which facilitated quick decision-making and strong direction” – love this – another awesome fragment of pre-production is the simple and unstated process of passing on the genetic material of the project’s soul to the audio designer/director/lead/person.

+ “This approach isn’t about convenience, it’s absolutely essential when trying to make best use of the limited amount of “oh crap, we’re actually finishing this thing” time at the end of a project” – You’ve nailed something here that i’ve found very difficult to articulate in the past – Being able to simultaneously hold an overall vision of the project’s soul AND be prepared to throw things away at a moment’s notice is another essence of the sound designer’s role – sometimes you meet/read about audio folks with approaches who are decidedly one or the other – extreme bureaucrats / chaotic creatives – “Chaos is the land of never getting anything finished, bureaucracy is the land of never getting anything started” – it is great to see the middle ground being so happily and effectively occupied here, using each as and when required.

Mm has a Studio Director who is a ‘listener’…

Studio Director Ensures…

“Audio present in meetings and up to date on the latest goings on in the project.”

“Gave the audio team an extra couple of weeks on top of the art and design team to finish our work to the required standard.”

“Sanctioned my desire to have all the content team’s changes and fixes buddy-checked by a member of the audio team in the last couple of weeks so as to catch the inevitable audio content rot.”

This is huge to have a ‘sound collaborator’ in that role. I know from reading this you realize the value, and rarity of such a collaborator. Awesome to read this here and see them being called out. That whole section ought to be in flashing red text!

Awesome Audio tools can decouple the audio designer from the rest of the team –

Man. We hear a lot about how positive this effect of audio tool enrichment has been, mainly from the developers of such in-house & middleware solutions/tools HOWEVER – because of these incredible tools, Audio Design now fundamentally requires MORE work on the social interaction and teamwork side now than ever. True, we used to have to spend a lot of time explaining what we wanted to do with sound, and coming up with nutty technical solutions, which sometimes were;t that elegant, but we were working with and collaborating with another human being, and it felt good! Now audio has to step up to have different kinds of conversations with the people on the team.

“The vast majority of audio implementation in Tearaway – everything apart from animation and hard-coded audio events such as UI and gameplay sounds – was done in the same proprietary level editor that the designers and artists were working in.” –

Love this. Playing in the same waters with the same toys is a big part of that team-work. The effects of each persons incremental changes is apparent to all. This kind of work requires good kinder-garten skills – sharing, listening, helping.

Loved reading this. Made me very happy. Can’t wait to play the game!

Aw, glad you liked it, Rob! Hopefully playing the game will make you happy too – Atoi has a unique message just for you :)

Great article! Love hearing about your team’s process. Excited to get my hands on the game to hear it firsthand.

Cheers Troy! Please feel free to come back and ask any questions if you have any after playing it.

Thanks for that article, I really enjoy it.

Awesome article, Kenneth. Thanks for sharing so many details!

Hi Kenneth, great read!

With that said, I still cannot seem to forgive you for the fact that “The Wilderness Theme” nor “The islands theme” from LBP were ever released anywhere :( :(