With this month’s theme of Pure Sound Design, there is no better time than now to talk to the creators of blind-accessible games that communicate their gameplay and stories through audio. However, must these experiences contain only audio? Per Anders Östblad—a Lecturer in Media Arts, Aesthetics and Narration at his alma-mater, The University of Skövde—doesn’t think so and shows this with his new game Frequency Missing, a point-and-click adventure that can be enjoyed by blind and sighted players alike.

In this interview, learn about his journey in blind-accessible games—from his Master’s essay on how computer games can aid the visually impaired, for which he received the Diversity Scholarship in 2012, to his recent project Frequency Missing, which was presented in his GDC16 talk “Audio-Driven Game Design“, and how he plans to further develop this model to makes games for everyone.

Hello, please introduce yourself.

PÖ: Hi, my name is Per Anders Östblad. I’m a 36 year-old audio designer from Gothenburg, Sweden. I work as a lecturer and researcher in audio design and music at the University of Skövde, Sweden.

First things first, how did you get into sound?

PÖ: I’ve always been interested in sound, music and listening. When I was young, my dad was somewhat of a hi-fi nerd and my mom played a lot of instruments. I often used to sit with my dad’s expensive headphones, the size of my torso, and listen to records. Or I would sit at the piano and try to make songs. When I was a little older we got a couple Roland synths and a 4-channel Portastudio, and I liked to play around with their sounds. We played a lot of music as well, and when I bought my first real computer I started making beats with a simple wave editor by copy+pasting. I learned a lot about audio editing that way.

What did you see yourself doing for a career when you started your education?

PÖ: When I started, I didn’t really have a clear vision of where I wanted to end up. But a couple of game projects in, I knew I wanted to work with sound for games. During our second-year game project, I got into the implementation side of audio and that interest just kept growing. I was surprised by how much sound design work I could do during implementation rather than recording/editing. By the end of my Bachelor’s program I knew I wanted to work with audio implementation.

How did you become interested in accessibility?

PÖ: During my years as a student I experimented a bit with audio-only games, but at that time I had basically no knowledge about the visually impaired community or accessible software and hardware. However, my interest in audio-only games led me to do some research into what games existed. This led me to realise how many people there are who use computers, smartphones and tablets without using graphics.

Then during my Master’s project in Serious Games, a friend and I got together with a computer-accessibility company and made a prototype for an audio-only game. In that company we met a blind guy who used his computer and phone with such ease by just listening, and I became fascinated with how much we can do with audio and how helpful it can be. We had this idea that if we replicated a space accurately in 3D with sound, it might be a way for a blind person to get familiar with a place before visiting it. That idea didn’t really turn in to anything useful, but the ideas from the tests we made eventually led us to win grant money from an innovation contest for a blind-accessible point-n-click game. That game was released last year, and we’ve been writing about and presenting our research from the playtesting results.

That game is Frequency Missing. Could you tell us a little about it?

PÖ: Frequency Missing is a short point-and-click adventure for smart phones and tablets where you solve mysteries and puzzles, explore environments, and talk to characters. The game has audio and interaction design that aims at making the game enjoyable for sighted as well as blind players. The game is currently only available in Swedish.

The reporter Patricia has just gotten her first job as a reporter for a radio station. But right away, weird things start happening. Where is Richard, her friend and colleague who got her the job? He’s been missing for three days… And who is tampering with Patricia’s news segments?

For your Master’s in Serious Games, you received the Diversity Scholarship for your essay on Audiction, a virtual environment for orienting visually impaired users to a physical space. Could you explain the development and execution of this project? What were your goals and expectations, and what was the outcome?

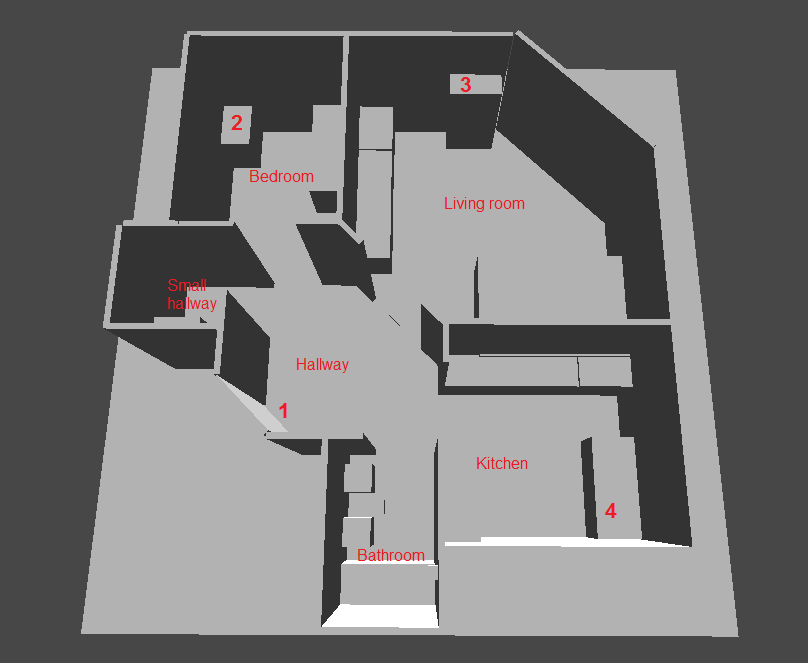

PÖ: We wanted to explore the possibility of representing a real space with audio only in game-form to see if we could let visually impaired people know an environment before visiting it by playing the game. My study-colleague Mårten Jonsson and I created one game each. I created Audiction, which is a 3D first-person game where you listen to realistic diegetic sounds and try to navigate without graphics. For aid, you have a virtual cane that you can tap in front of you, and the objects you hit have different sounds depending on the material. Mårten created a 2D game, Audionome, for touch screens with informational sounds rather than realistic ones. We chose an apartment on campus, measured the place in detail, and I recorded ambiences and objects in the apartment. Then we built our two games to match the apartment—mine with as accurate of sounds and ambiances as I could accomplish.

To test the games, we invited a bunch of sound and music students to the apartment. They could not see the apartment before the tests. One group played my game, one group played Mårten’s game, and a control group did not play any game. The objective in the games was to locate three objects around the apartment. After playing, all three groups were fitted with blindfolds and told to find the same three objects in the real space like in the game. Between and after sessions they filled out questionnaires and drew maps of how they thought the layout of the apartment was.

This was just a pilot test since we didn’t have any visually impaired testers—plus we had so few subjects and too little time during the tests. No significant results were found, and I have since given up on the serious application of this type of game; however, I learned a lot that I can use in the accessible games we now develop for entertainment. To quote what we wrote back then: “It was concluded that the concept of Audionome, with the diegetic spatial audio of Audiction, would most likely be a good way to convey spatial information about an environment without the use of visual stimuli.” And that conclusion is kind of what we used as a start off point when developing Frequency Missing.

How did you apply what you learned from Audiction in Frequency Missing?

PÖ: The major things we brought with us into Frequency Missing was the use of “point sounds”—diegetic audio-representations—for objects in the game world. And from Audionome, we took the 2D interface for touch screens where the player drags one finger across the screen to listen. We also learned a lot about how difficult audio-only navigation is, especially if you have “untrained” ears, and the importance of playtesting and game development in general.

What are some of the general challenges you come across when creating blind-accessible games?

PÖ: The absolutely most challenging aspect is that I, as a sighted person, can never fully understand how it is to be blind. So we’ve had to learn a lot about audio-only interaction and accessibility, and we’ve had to do a lot of playtesting through every step of development.

Another challenge has been learning the hard way that even though my designs or my sound design may be obvious and clear to me, it might not be to the target audience. And that’s not the audience’s fault, it’s mine. You would think that it’s obvious, but I don’t think I really got it until I’d had my “darlings” ripped apart by frank and honest kids playtesting our game. I believe I’m more humble and a better game audio designer for it.

I personally also learned a lot in audio design by working towards the hypothesis that the audio in a blind-accessible game can’t be immersion-breaking, not if you want the game to be equally enjoyable both with and without the use of graphics. I’m not gonna say it’s easy, but it’s easier to just make a game playable audio-only. To create a truly immersive experience I believe all the interface audio, voices, etc., that you use for information and navigation has to merge with the rest of the soundscape and game world. It’s a bit of a balancing act to design audio that is both natural enough to create an immersive experience and clear enough to be helpful. When done well though, I believe the overall experience of the game can be enhanced for any player, playing with graphics or without.

Why do you think it’s important for blind and sighted players to have the same experience?

PÖ: I think it’s important to be allowed to take part in popular culture regardless of who you are. Gaming has very much become a natural part of life for many. Letting people share a gaming experience with others, either by playing together or by discussing the experience, is a good way to include more people in gaming. With FM we felt that for all players to be fully included in the design of the game, the experience needed to be comparable. With that said, not all game genres are as easy to make equal with or without graphics, and they don’t have to be. Every game that is accessible or inclusive to one extra person is still a step forward.

While working on Audiction and Frequency Missing, had your perception of blind gamers changed?

PÖ: Yes, a lot! I had absolutely no clue whatsoever about audio games or blind gamers, so I learned loads about accessibility on iPhone, PC, and everything else. As I mentioned before, while working on Audiction, we got to hang out a lot with a guy who was blind who taught us a lot about how he does things. He had an audio engineering degree and worked as a software developer, and those things alone made me realize what accessibility really is and how important it is.

For Frequency Missing, my perception changed especially when it came to mobile use and gaming. It was very obvious when we did playtests with visually impaired kids that they loved to play games but there were very few to chose from, so we were met with a lot of positivity!

Since blind-accessible game development is a still developing field—and it was an even less heard-of topic when you were pursuing your Master’s—where did your motivation for Audiction come from?

PÖ: This is gonna sound stupid, but it was from a game I made in school—an audio only beat-em-up game. It was simple and not very good, but it got me interested in what had been done with audio only. So I started Googling or Eurekaing (or whatever search engine I used then ?) and found a bunch of audio-only games, but they were very hard to learn. Mårten and I wanted to make something that was more accessible to people who aren’t used to playing PC audio-only games—something more intuitive you might say with easy controls and where listening is everything. Along with including visually impaired players, not alienating people who aren’t used to playing games is kind of the goal with FM as well.

Do you feel your motivation changed with FM?

PÖ: Yeah, absolutely. Now we have tried things having no idea if they would work, so the drive to make more games in a similar fashion has really gotten boosted! My interest in accessibility and research has also been strengthened. That we actually succeeded in creating a game that can be interesting for both blind and sighted players was very motivating. I mean, we only have a few downloads, no awards, and we’re aware the game is nothing spectacular, but the main goal of creating a similar experience regardless if you play with or without graphics has worked! Now I want to make better games with the same principles.

Could you tell us about what you’re currently working on?

PÖ: I sadly can’t say too much at the moment, but we are using the methods we developed in our last game for a new game. It’s an exciting collaboration with a big company that works in linear media. If everything goes to plan, it’s going to be kind of a transmedia experience that’s fully blind-accessible. We are also currently looking into translating FM to English and publishing it in other countries besides Sweden.

I can also mention an interesting fact from development. When we started prototyping in Unity, we ran into the issue that when iOS VoiceOver was turned on it would disable “regular” touch gestures. So we e-mailed Unity, and poof—maybe one week later—they had patched it and now it works great! Meaning we can make our own audio interface and blind players won’t have to disable VoiceOver before starting the game. I think it was just a bug, but they were very keen to fix it and that’s great!

Where do you think blind-accessibility is heading?

PÖ: I definitely think more and more people are starting to realize there is such an issue as accessibility, and that alone means there are many more people who might be interested in working for more accessible tech and games. I think we will have a lot more audio-focused games—and the better the binaural engines and plugins become, the more advanced things we can potentially make. As audio people, we might benefit from this as well if accessibility means more focus lands on the audio.

Finally, do you have any advice for sound designers interested in accessibility?

PÖ: I would say play audio games and accessible games and read forums where gamers themselves talk about the games they play. You can learn a lot and get great tips and inspiration from what, in this case, blind gamers think about different games. And when creating audio for an audio interface, mix clarity is very important. Make interface sounds stand out by giving them a focused frequency range or by spreading the stereo a bit more, for instance. And try to be consistent with interface sounds, perhaps by creating a “class” for all informational sounds so they stand out and players can learn them (consciously or subconsciously).

Every little thing counts. If you can design for everyone from scratch that’s awesome, but even if you make a game somewhat accessible afterwards by patching, it has a lot of value. One more person can enjoy another game.