Guest Contribution by Rob Bridgett

For the past 14 years I’ve been a proponent of sound as a deeply integral part of the video game development process, getting audio involved earlier, allowing it to become a part of decision making and concepting, allowing sound’s early presence, excitement and enthusiasm to influence the other disciplines involved in the collaborative sport of video game development.

Recently, you may have noticed a trend towards narrowing down the focus of what we consider to be multi-disciplinary game development, there are small team, minimal, retro, and almost inevitably towards audio-only games. At the Game Developer’s Conference Nicky Birch of Somethin’ Else’s spoke about their audio-only games (such as Papa Sangre) as did Brian Schmidt on a similar theme in 2013). These are games in which the player has little or no visual input or stimulus, but relies entirely on spatialized audio cues.

These games cannot really be described as audio-only in disciplinary terms, because there is a considerable amount of what we’d call ‘design’ that goes into these titles. In fact, the design is still very much the bones on which the sound hangs in these titles. But, in terms of player-experience, the graphic or visual elements are no longer present.

Much of the philosophy underpinning audio-only games is built around absence. An absence of visual cues means that we, as players of these games, inevitably need to rely on an entirely imagined rendering of the sounds, spaces and entities that are presented, and this is a big part of the thrill and difference of these experiences. Like radio drama for much of the 20th century, what began as an almost literary entertainment experience, changed dramatically in style with influences from Orson Welles to docu-drama and docu-comedy styles prevalent in film, television and other ‘visual media’, all informing the way we visualize what is presented in sound.

Thinking about this trend has me both excited and also a little worried. While the scope for a ‘pure’ sound, and design, led experience offers a massively tantalizing production environment and artistic breadth, I can’t help feel that the role of visuals is being demoted a little unfairly in these kinds of experiences. I still believe that sound and visuals are at their strongest when they work together and hand over between one another. That is not to say that there shouldn’t be moments of silence, or for that matter moments of darkness, but that when these areas are sequenced and presented well, with good collaborators, the results are so much more powerful. The cynic in me feels that audio-only games, to some extent, might be a result of the inability of sound and artists to collaborate, that maybe the ‘people stuff’ has got in the way too many times so ‘screw it, let’s make an audio-only game, we won’t have to worry about rendering any graphics or have to pay for any either”. But I know that’s not true (is it?). Yeah? No.

So, as an antidote to this, and as a kind of mental exercise for audiences, artists, game designers and for sound designers, let’s consider a game, a movie, or any kind of experience that is designed specifically to be visual only. Many of these exist already, like the curated art gallery experiences in so many of our museums and art galleries. The ideal situation in which to experience works of art, painting, installation (that aren’t designed to be sonified), we are told through gallery design, are quiet, crisp and clean art gallery spaces.

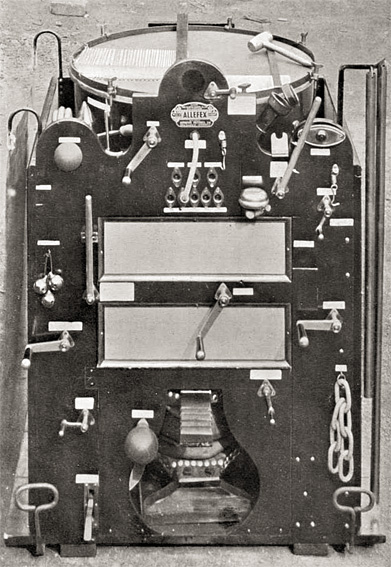

Silent film, though it already of course existed for around 40 years prior to the arrival of sync sound, was always intended to be sonified in some form or another, whether by musical accompaniment, or through sonification via machines such as the Allefex.

Watching an old silent movie without any kind of musical or sonic accompaniment you can start to see some of the design details necessary for the medium to exist. Inter-titles to display important or critical dialogue and scene descriptions, acting styles that by today’s filmic standards, massively over exaggerated emotions and movement, and on the whole, snack-sized running times.

Watching a silent movie, in silence, no music, no accompaniment of any kind, is any experience that is nearly impossible for us to focus on. I guarantee you will become distracted by the next loudest thing in the room. We hear sound all the time, we can’t shut it off voluntarily as we can with our eyes. But do we start to sonify silent experiences inside our imaginations in a similar way that we do when we hear a radio play (have a mental image of the look of an actor portraying a character), or when we play an audio-only game? We’ve heard talk of the imagination being the best rendering engine that we could possibly have for visuals, but can we talk of the imagination supplying sonification for silent experiences?

As sound designers, we’re often presented with a completely silent piece of animation or film, and are expected to go through and sonify the experience, adding in layers of background tone, Foley, fx, voice, but also spatialization through reverberation and panning. As part of the early spotting process, we’re quite used to watching these silent pieces of footage an imagining what needs to go in there, or what might work well. Some still work in this way with sound cue sheets, time-based maps of imaginary sounds. This completely imaginary process of spotting sounds is really interesting because I’ve always imagined sound and had a very clear idea of what will and won’t work, but the actual sound that is realized and produced is never very close to how I imagined it. It is as though between imagining the sounds for the piece, and in producing the sound, a massive amount of translation has occurred from conception to implementation.

I feel that a good work of art can imply sound. Picasso’s Guernica springs immediately to mind in its implication of noise, screaming, the sounds of war and horror. Italian futurists and Russian constructivist art implies big, brutal machinery and noise. Similarly comic books explicitly imply sound though the sound effects written out in them. Kerouac’s novels bristle with music, sound, language and rhythm. All of these are mediums, which provide a sonic experience to the viewer, or reader, but do not produce or emit sound.

One of the biggest questions for us as sound designers no longer seems to be “What sound should it make?” but “Should it make a sound?” Is a sound always necessary? Adding too many sounds will always result in a final mix decision being made to diminish other elements that are unnecessary. In the case of Battlefield’s HDR sound culling mix system, the question is clearly always defined as what range of sounds are most important at this particular moment? When a motion picture is being mixed, the question is similarly about focus, what sound is the most important at this particular moment for the audience?

Should there always be a sound? Is their room for silent game experiences? Would a silent game necessarily feel incomplete if it were designed with this in mind? With every detail sonified, are we robbing the audience of their sound imagination, of their ability to sonify the silent?

I believe there is so much more scope for silence than the current clichés of hearing loss or emotional detachment.

As an experiment, watch this beautiful music video, which is in many ways designed to be ‘silent’, with the sound turned down completely, and enjoy the sounds that your own imagination can provide.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/92767692[/vimeo]

There are a lot of questions that surface with a silent exercise like this. As a sound designer, the thing I naturally imagine, simply through the practice of having viewed many silent pieces of video in spotting sessions, is to imagine the ambience and background fx that would be required to fill in and make it sound real. Watch the sequence again and just imagine yourself an actor, you are imagining the dialogue between these characters. Watch it again, but this time assume the role of a composer and imagine the musical textures and motifs that may work for the piece. Watch again as a mixer, imagine sounds, music and dialogue all together, It is through this role playing that I’ve come to realize that the act of imagining sound is one that gets easier with practice.

Is there scope for a truly silent game? Perhaps not, or perhaps there is only very limited scope for a completely silent game. A game that mixes between modes of silence and of audio-only, the interplay between these two modes could have a more interesting appeal, especially with a great set-up and framing device for this. Ultimately I think a mix if these two extremes, handing over between one another, is a more enticing and fascinating area of interplay and collaboration.

This is a very interesting topic. In my opinion there is no scope for a truly silent game. Because “silence” on it’s own doesn’t exist. To me, silence is simply “the absence” of sound. Without preceding sound, there’s no “silence”. I think you’ll always need some kind of sound/visuals to have a player immerse into a game. Only then you can manipulate his experiences through introducing silence again. If there’s no sound to begin with, contrary to how a sound designer might react, I guess most of the players will just continue to experience the sound of their current environment.

Interesting article and points. Perhaps some of these sound-only really are the result of a bit of “us-and-them” polarization – who knows? Or just sound geeks geeking way out?

You don’t mention them, but the blind or near-blind are certainly part of the scope for sound-only games (or films). I know blind people are gamers too, though I know nothing of what games they play or how they play them – perhaps someone could write an article about that here on DS?