Guest Contribution by Randy Thom

During pre-production on a film it’s common practice to gather lots and lots of still photographic images, and video as well, that might relate to the story. The stills are often displayed on walls for everyone preparing the film to see and talk about. It’s basically an “idea board.” The purpose of gathering these images is to stimulate thinking about the way the film should look, or about some other element of the story taking shape. Shots of potential locations for shooting, or locations evocative of those in the story, images of objects and props, shots of people similar to those in the story, animals, food, vehicles, landscapes, structures, etc. are compiled as concrete starting points of reference for constructing the look of the movie. Eventually a storyboard artist will draw images representing almost every shot in the film. It’s a way to help the filmmakers pre-visualize how each shot will be designed.

Usually the only sonic research like this is done for music. Especially if there is likely to be source music in the film then some energy will be put into gathering music that might either be used in the film, or music that can start the conversation about what will eventually be used.

It seems odd to me that gathering other, non “musical,” kinds of sounds in pre-production is so rare. It seems odd, but it isn’t surprising. For reasons I don’t understand, we as a culture resist using sound as a starting point. It’s the tradition for sound to follow, not to lead. But that’s strange because we also know that sounds are evocative. Sounds suggest images at least as much as images suggest sounds.

I think it would be useful to have a sound idea board for many films. I don’t have any doubt that listening to sounds of places, people, vehicles, animals, machines, etc. would not only be a concrete way to begin figuring out how the movie should sound, it would also stimulate thinking about visuals, and would sometimes suggest compelling shots that wouldn’t occur to anyone who was thinking exclusively in visual terms.

Yes, there is an enormous amount of inertia that would need to be overcome to get productions to spend time and money gathering sounds in pre-production. It isn’t going to happen quickly, if at all as a frequent occurrence. But I think it’s worth pushing for whenever there are filmmakers who might be open to it, because it will make better movies. I’m writing this to start a discussion. What do you think? I know many of you will say it’s nutty to shoot for things like this when we often can’t even get productions to pay for things that are patently obvious. My response is that I think we need to push the idea of sound’s importance at all levels. Some directors who wouldn’t consider giving us another minute to adjust a mic on the set will love the idea of a sound idea board. Sound needs to get its foot in any door that’s cracked open. It’s good for us, and it’s good for storytelling.

We do experiments like this at Volition. A recent example is that we had an in-house writer create an in-game scenario that might happen. Then one of our in-house audio designers (Aaron Gallant) designed a sound scenario based on the text. Then we played the audio for the team (without any visuals) and it was a huge success. Now we’re looking at taking the audio and having our concept artists draw some story boards based solely on the audio.

Anyway, totally agree — it’s about experimenting with new processes that can help define the vision of the project in new ways.

We’ve done lots of other experiments, like hanging mp3 players next to pieces of concept art that had music on them that you could listen to while looking at the concept art, or doing audio-only first-person walks through areas of the in-game world before they’ve been created…

Thank you for writing this up, Randy.

Agreed, and it’s something that in some small way takes place within video games, Ariel’s tale being a great example of that.

I worked on a research game project at MIT, a game set in 1950s rural England for which I created a piece of concept audio, something like a sound tapestry of what a “day in the life” of a typical citizen might sound like. It wasn’t an asset used in the final game but served a similar function to the concept art that the rest of the team were working on. It’s explorative, world-building and defining.

This kind of preparatory work saves time (and time = $/₤/€/¥) when post-production begins because the sound of the thing is already largely defined. It would seem to me that film stands to benefit far more from this kind of work as games often benefit from an iterative approach in all departments, morphing and evolving throughout production. This lends itself quite well to continued conceptual work. Film on the other hand is far more focused on getting the thing defined in it’s entirety before the camera even begins to roll because of the fixed nature of film, even digital film. The script has been written, it’s been budgeted, there’s a screenplay, there’s concept art, pre-vis, it’s been cast, there’s a schedule of which shots will be taken when… you get my drift.

So yes, I agree and being able to dip my toes in both worlds has allowed me learn that there’s certainly more resonance for this kind of work in games. There are two factors that immediately come to mind that I think support this.

Firstly, in film, by the time a sound designer even get’s a call about the project, it’s quite possible a concept artist has finished their work on the project a year ago, half the picture is already shot, and there’s a rapidly approaching release date. The timeline of pre/production/post doesn’t help us much as we’re the last domino to fall. That hurts the opportunity for cross-pollination between creatives.

Secondly, film seems to be largely defined by one vision, the director’s, to which all others try and realize. Games typically have more of a collaborative leadership in terms of design. By the very nature of this dynamic, there seems to be more of a willingness in games to allow audio to explore, try something, even contribute to design and narrative. In film, it’s often the case that the director is protective of their vision, understandably so when there are often others pulling at it in various directions. As such, I often work under the impression that they know exactly what they want to hear in their head, and I’m told what that is at the last second so I can do nothing other than try to produce that and hope nothing was lost in translation along the way.

Randy, you once mentioned in an interview that despite experience, you have to do a lot of experimenting with every project, making lots of mistakes and going down dead-ends. I always stress when I deliver concept work that I don’t just need to know what works, but that I absolutely need to know what didn’t work as well. They say we learn more from our mistakes and I always try to make as many as possible, sadly however, film often doesn’t have time for them.

Great idea, Randy. Anything to start the conversation and open some minds will advance the art of film and film sound. I’ve heard of only a few instances where sound was created specifically to play on set during shooting to inspire the actors performances. This would clearly be a later step in the process you’re suggesting we start, but it’s a great idea too and worth mentioning.

Very interesting. I’ve worked on several commercial jobs now and I’ve always enjoyed the pre-production process with my director/producer as he’s usually the one single-handedly putting together the storyboards and mood boards. He likes to bring me in because he knows I can see the visuals he’s after, consider the locations he’s choosing and discuss potential problems and workflow solutions or methods for capturing location sound during production, and what the end sound mix should ideally be.

On my own scripts and treatments a lot of my narrative ideas are musically driven, and while I write I will be listening to inspiring music for the mood i’m trying to write the scene for. I then take notes of which songs really worked and that I feel were worth noting and where I referenced them for writing purposes. I’ve taken this even further as I am writing a new concept right now that is very sci-fi but very close to reality, and I’ve been experimenting with synthesis sound design and capturing quick “sketches” of sounds for ambience or rhythmic motions that could be used as environmental noises as well as straddle into the music elements. When I get closer to starting the actual treatment / narrative script I’ll be building storyboards to convey the visuals that will drive the story and build the aesthetic, with reference to the sound design cues I’ve been developing. It’s a very good practice indeed!

putting ideas into any concrete form is always a great idea!

This would definitely be an interesting way to start, I think it would create different results visually than starting with the visuals to come up with sound! Something to think about for sure.

Another great post from you Randy, thanks for writing and sharing.

I think the idea is solid, any process that will allow a direct interaction between the sound team and the production team is always going to beneficial. I strive to interact and conceptualise with directors and creative leads as often and as early as possible, to ensure that we are both working to the same vision and maximising our time accordingly. Although a lot of pre production planning and processes I have suggested in the past will be ignored, even if the director/creative in charge is forward thinking enough to bring sound in early. I often find that the idea of additional time spent delving into audio in pre stages is not a priority and often gets overlooked, then the deadline closes in and the stress levels rise.

Obviously this is not the case every time, but it happens more often than not and it is a shame. really.

I would love to work on a project that had a sound storyboard, it would bring a lot of organisation into the recording/designing process and allow for early sounds and ideas to be heard and altered way before the mix process, resulting in less “revisions” and heartache later in the process.

I can’t remember who came up with this idea (I know it’s on designingsound.org somewhere though), but the idea of the sound bible, where everyone involved in the production can contribute audio examples or ideas to one book (or place) that the audio team can take direction from. I have been using this technique since reading that article (Sincere apologies to whoever wrote that article, my searches did not return any results, but thank you for it – it has served me extremely well).

I will often setup a dropbox folder and share it with the director and producers etc and encourage them to upload music, youtube videos, descriptive words, video games, film titles and scenes that they like the sound of and are influenced by. This allows me a greater insight into their vision for the project etc. It helps creatively, for the design aspects, but not so much for the hard facts like locations and particular field recording sessions that will need to be planned. If the storyboard and the “Sound Bible” were implemented together then the sound team would be unstoppable and able to deliver exactly what the film and director needs, probably first time too.

My next project (if brought on early enough), I will try and grab a storyboard and attempt this method, even if it just for my own benefit.

Thanks again Randy.

In the School where I teach sound theory and how to create sound scape for a movie, I ask my students to record, edit backgrounds/ambiences – create examples of SFX – compose some music leitmotiv – all of this based on the script and discussions with the directors before the set recording.

The schedule are so « time-stretched » that I recommend to my students to start to record / edit the ambiences when they go to potential locations. It is also important that we teach students in directing how the sound crews can perform the soundtrack to serve the emotion.

The experiences for every movie are very interesting and enriching: we always learn new things and open our mind.

We try to teach our students (directors – sound crews) to collaborate in the best way. But they also have to experiment, to make mistakes as Richard Gould says.

Thank you, Randy. If you come to Paris, may be you can meet my students!

Didn’t Ben Burtt work on WALL-E as an in-house sound designer? I remember I was very suprised when I read that for movie production that was an EXPERIMENT. I am from game industry and for me – sound designers, artists, animators, writers, sometimes even music composers working together in one building – its is just usual, normal thing.

Maybe movie audio production can learn something about it from game industry :)

Thanks for all the responses, and especially for the examples of this kind of approach already being used. I’m not surprised that it’s mostly happening in games, where there isn’t as long a history of ignoring sound until the last minute, which is the dominant tradition in film. (Though I know that games are usually not exactly sound Valhalla either.)

The persistent myth that film directors know “in their heads” exactly what their films should sound like is such a crock. Yes, many directors have have a sound style in mind. They can list a few existing films as models, and refer to specific sequences and specific sounds in those films, which is helpful to us; but the notion that a director has the perfect sound for a given moment in his/her head, and our job is to somehow guess what it is, and give it physical form is… ridiculous. It’s the opposite of collaboration. Collaboration is about figuring something out together, and the result of collaboration is always different from what either of the collaborators imagined in the beginning, whether they’re willing to admit it or not.

Yes, Ben Burtt was involved in Wall E very early, and his sounds helped shape the visuals for the film. It’s a wonderful model to study. (By the way, when the story was first being developed one idea was that there would be no dialog at all in the movie. How amazing THAT might have been!) The kind of early sound experimentation Ben did on Wall E could help many, many films. His experiments were focused on the central character of the film. What motivated me to write this piece is a broader notion about the influence sounds could have on developing a story. Some sounds gathered in pre-production would relate to specific characters, locations, and objects; but many sounds in the “idea board” would be mainly useful in terms of mood. The more the storytellers listen to sounds early-on, the less they are likely to think that they need to fill every moment with words and/or music.

Randy

I totally agree Randy.

This is the way I’ve had the privilege to work on the last 3 of Ben Wheatley’s movies.

I’m on the production from the script stage and Ben and I begin designing sounds together early, before the shoot even starts.

The script informs the sounds and the designed sounds influence the shoot and the way that certain scenes are filmed. It means the edit can be smoother too, because key sounds for scenes are ready to just drop in. They help pace the cut and because they are already agreed on, they make it through to the final mix with no changes.

Preview screenings have a more ‘finished’ feel too and that has obvious benefits also.

I think its a great way to work and I agree that more Directors and Producers should realize the benefits getting the sound department on a film early can bring.

It takes a Director that has a love for sound as big as ours, but thankfully more and more new Directors seem to be aware of the awesome power of sound in their work.

Exciting times.

Martin.

Great Words Randy! You’re Right on Track for Shaping the Future of Film Making!

Hi all,

I’m Ben Osmo, an Australian production sound mixer.

Thank you for all your thoughts.

I’ll try and incorporate these ideas in the next couple of projects.

On all productions I work on, I always try and engage with the sound designer well before preproduction. But its not always possible as the producers and director seem to be preoccupied with visuals and refining the script.

However, there have been some wonderful exceptions in the last few years.

The most recent I’m not able to elaborate at present until the film’s release, but suffice to say that all departments worked together very early in preproduction to achieve a unique soundtrack.

Chhers,

Ben

Thanks for your thoughts Randy! Here in Mexico, sound is almost a non-existing persona in the film production process, it is only considered for dialogues, and “in the end” when the picture editing comes in, maybe sound comes in, probably will be after a locked picture. Its too sad but it is our duty as sound editors/engineers/designers/mixers become collaborators, to be the second leg and make an impulse with the image, pair to pair. Sometimes the ignorance on sound is so deep we often hear from directors: “here´s the cut, put some ´soniditos´(little sounds) to dress it”, its basically a lack of culture and even sadder a lack of interest. We should implement this kind of ideas with the directors, a storyboard with sounds, a sound script along with the screenplay, references, etc.

There is so much to can gain as a film community by pushing this concept. I believe you mentioned something along these lines at the Golden Reel Awards this year Randy and it definitely caught my attention.

I think the bottom line here starts with education. Of course, that’s a long term solution, but we need more educators like Marie-Pierre BAI (commenter on this thread), pushing sound as an early collaborator from the get go on to film students.

I’ve been lucky to work with clients who take great pride in the soundtracks of their films and television series. It’s these kind of filmmakers (that see sound as an equal contributor to picture) that allow us to really explore our craft. If we can find a way, over time, to work the importance of sound into film education, I think we will see some really special things start to happen in our industry.

Thanks for getting the conversation started.

-Jeff

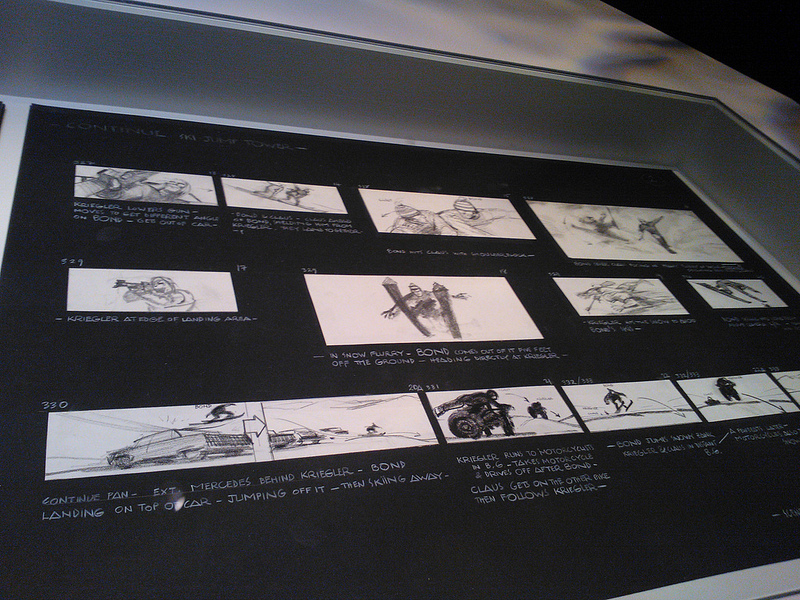

AS a first year student at the university doing Marketing I am working on storyboard which similar to the above (the BOND ONE) but mine is talking about the client walking into the shop to purchase clothes. Yes I did manage to draw up all the visuals but now I do not know how then I should add the sound effects to those visuals