Guest contribution by By Douglas Murray

OK, here is the ugly truth for film post, or really any surround sound work… Most reverb plug-ins do not sound natural for applications using greater than 1 or 2 speakers. What you don’t want: a reverb that jumps to completely different speakers from the source. What you do want: a reverb that spreads out from the sound and helps localize it and define the space it’s in. While I haven’t tried every reverb or surround reverb plug-in for Pro Tools, it’s a very exceptional reverb that sounds localized around the position of the source signal without having to pan the reverb return’s output. The focus of this article is localization of reverb in post for sound effects, dialog, and other discrete sonic events. Localization is of less concern for more enveloping sounds such as ambiences or music, which seem to tolerate more general spatial spreading.

In this article I’ll describe:

- why it is desirable to have the early reflections and reverb bloom outward from the direction of

- the source signal as in nature,

- how these principles must be exaggerated for the theatrical film sound environment,

- how stereo reverbs require panning to work in a multi-channel world,

- how most multi-channel reverb plug-ins largely disregard the direction of the source sound,

- how to simulate reverb localization with existing plug-ins in Pro Tools (more work and less accurate than it should be, today),

- And finally, I will describe a reverb plug-in that does what I want it to do. It seems so simple and obvious! Why is it so rare?

Natural reverb

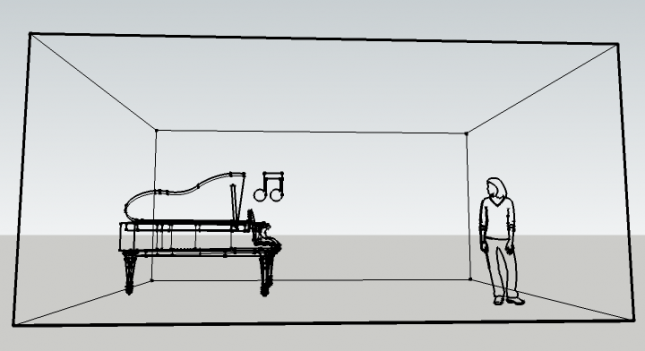

When a sound in nature is emitted from a source it travels quickly (depending on the distance [1] between the sound source and the listener) directly to our ears, and we first hear that “dry”, direct signal relatively clearly (though more-or-less attenuated by distance and filtered by the non-linear frequency absorption of the air). See Figure 01a.

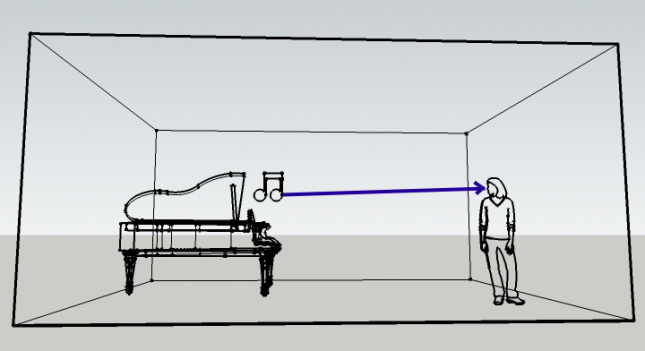

Very soon afterwards (depending on the distance between the source and reflective surfaces both near and far) we hear the earliest reflections from the surfaces closest to the sound source (and closest to us if we are near a wall or other reflective surface) since the shorter pathways get to the ear sooner and louder. See Figure 01b. Reflections bouncing off intervening floors, ceilings and nearby walls (even walls behind us) are heard earliest.

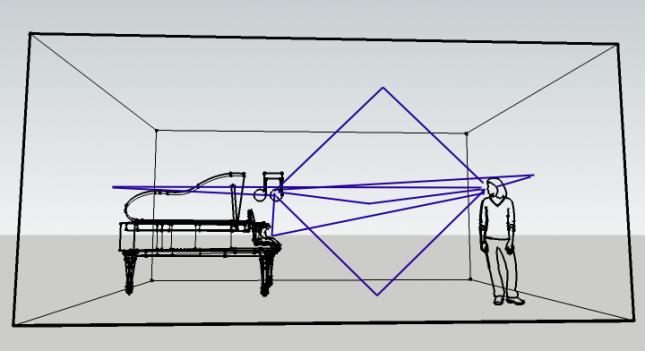

As the milliseconds unfold, more and more and fainter and fainter reflections are subsequently heard from a wider and wider range of directions. See Figure 01c. Finally, the latest reflections of sound arrive from all directions in a diffuse reverberation until the sound fades into inaudibility. The amount and timbre of reflections and reverberation is dependent on the acoustical reflectiveness of the surfaces and their positions around the sound source and listener. Though, sadly, we don’t have the aural acuity of bats, these reflections tell us a lot about the space we are in.

Many of the earliest reflections come from the general direction of the direct source (with some reflections from the side or rear depending on the exact room surfaces) followed by quieter and more diffuse reverberant sound blooming from a progressively wider sound field.

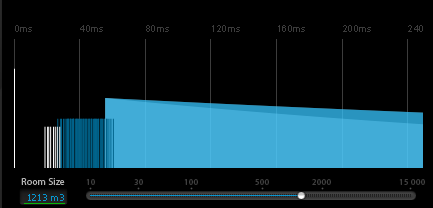

In this display the direct sound is shown as the highest (loudest) bar on the left. It is followed after a period of milliseconds (≈18ms in this case) by the early reflections and then by the diffuse reverberations. There is a gradual change from ER to reverb, shown by an overlap between the two (≈55ms in this case).

Requirements of cinema sound

Because of the widely spaced speakers in a movie theater, we have to exaggerate the localization of a sound. A sound panned widely will sound like it’s coming from the direction of the speaker closest to the listener, since its sound arrives first [2] at the listener’s ears from there and is loudest in that direction. In a recent email, Arjen van der Schoot of Audio Ease admitted,

In all honesty I do not know why panning the early part, and having a reverb that blooms from the source direction would work better. I only know it does.

I’m going to speculate on why panning the early part towards the source and letting the reverb bloom outward sounds better in film mixes than relying on the perhaps “correct”, but too subtle (for theatrical spaces) spatial effects of most multichannel reverb effects. The time frames between direct sound and ERs and between ERs and reverb are measured in milliseconds and are not distinctly heard and are not at all seen on meters, except perhaps in very large spaces. Remember, we are talking about film sound for theaters here, and in theaters the speakers are far apart, so we have to think about the precedence effect or Haas effect.

In another recent email, Michael Carnes of Exponential Audio pointed out a serious consideration for film sound,

If you’re not seated in the sweet spot, the Haas effect draws your directional sense to the closer speaker.

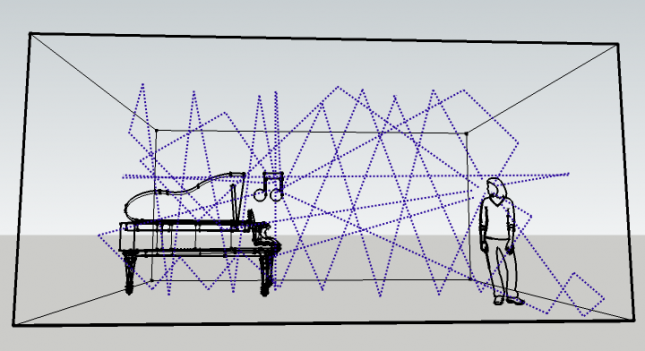

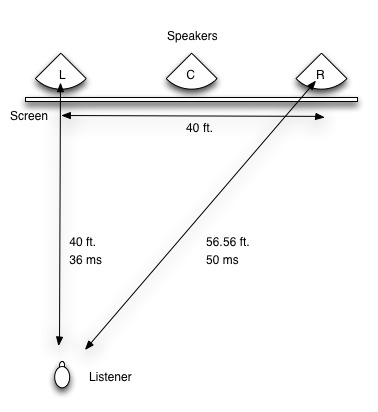

Because of that any localizing effects have to be exaggerated to be heard more or less as intended in all the seats. For example, in a 400 seat movie theater with a screen width of 40 feet, someone sitting 40 feet back from the left speaker will hear a stereo (LR) sound from the left speaker first unless the sound from the right speaker (57 ft. away) is emanated more than 14 milliseconds earlier. See Figure 02. So if you want to make the reverb for a sound on the right sound like it’s coming from the right to someone sitting on the left, you have to not let any part of the sound be heard from the left until at least 14 ms after the ERs are heard on the right, the reverb portion of the effect would be heard later, depending on the size of the space in the film. The problem with this is that if the room the scene is taking place in is smaller than the size of the largest screen you will play the film on, then delaying the reverb on the left enough to hear the right speaker first will make the room sound too large for the scene. In this case just leave the reverb on the right or widen only to the center.

People sitting even closer to the screen will have a more difficult time getting the intended localization.

Arjen also said,

What I do know is that many times when a reverb is used, it is too loud, because lots of people want to hear what they do. In fact, if you smalltalk in a forest or a cathedral, there is no reverb of significance.

Arjen has given us another answer to the problem of localization of reverb returns: turn it down! Exaggerated levels call attention to themselves, however they are panned.

While creative non-natural uses of reverb can be a wonderfully expressive tool for sound designers, an understanding of the physics and psycho-acoustics principles of how reverb works in the natural world helps make us better at our work. And since verisimilitude is often what we are going for, getting natural reverb right is important.

Panning stereo reverbs into a wider space

As shown in Figure 01a, the “direct” sound comes directly from the source. To (somewhat elaborately) simulate this in a 5.1 space, pan a mono sound to the screen location of the source. In its crude way, Figure 01b shows that the early reflections come mostly from the general direction of the source sound. The early reflections create a sound field that localizes from around the source position like an expanding corona. To simulate this in 5.1, pan a stereo reverb return, with the early reflections on and the reverb tail turned down or off, to bracket the position of the dry signal. As the sound reflects and scatters further we get the later and quieter reverberations of the sound dying out which is more diffuse and omnidirectional. Figure 01c. To simulate this in 5.1, use a second stereo reverb with the ER section off (or lowered) on a separate return with its own panning set wide and halfway between the front and rear speakers. See Figure 03.

This is more work for both the mixer and for the computer than sending to a single stereo reverb plugin and returning the combined ER and reverb to the same spread in the surround space. A similar technique is to render the ER heavy sound using AudioSuite in Pro Tools (rather than sending real-time to a reverb plug-in) and panning the resulting ER and the dry sound in the tracks. Then send these sounds to a single room reverb, returning a wider spread sound. That saves some processing overhead.

In order to streamline this tedious process, it’s much more common to use a only single stereo reverb panning the output narrowly into a 5.1 space, like you would the earliest reflections, or somewhat wider, to taste. That works well and sounds good for most uses.

The problem with stereo reverbs in film mixing in a 5.1 or 7.1 environment is that they need constant panning to sound plausible. Let’s say you pan a sound to the center channel and also send it to a stereo reverb on a stereo return panned hard left and right. Each time there is a sonic event in the center speaker we hear a delayed bounce (by the predelay amount) in the left and right speakers, and no reverb at all in the center to accompany the dry source sound. When mixing for stereo with a phantom center channel this can be an appropriate technique; for LCR film mixing with a hard center it doesn’t sound right.

Using multi-channel reverb plug-ins doesn’t help

Most currently available reverb plug-ins are designed to produce a reverberated output delivered roughly evenly across the available output channels with the early reflections and the diffuse reverb coming equally from everywhere. So a mono signal sent to a typical 5.0 reverb plug-in returns the ER and reverb from all 5 output channels at roughly equal volume, with little or no localization, no matter which channel you pan the input to. In nature this would only happen if the sound source and listener were both in the exact center of the reverberant space, which is unlikely. So we have an unnatural effect, which has to be fixed in post: pan the output of the reverb return to match the desired space. Since this is complicated in Pro Tools where you can’t simply pan a surround output, the common workaround is to use a stereo plug-in panned into a 5.0 (or 7.0) return (as described above). A less common solution is to use a 5.0 aux input track with a panner controller, like Spanner, anymix, SPAT or S360 Imager inserted after the reverb plug-in to control the output panning.

It would be much better if the multichannel reverb plug-in’s algorithm followed the send pan position and handled the output panning itself to create a more natural sense of acoustic space in the mix. I’ll discuss this more later.

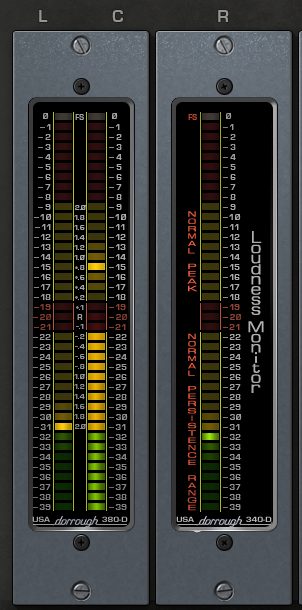

Here are a few examples of how mixers use reverb return panning to create a more effective mix.

There is a cinematic convention of keeping the dialog panned to the center at almost all times [3]. To use a stereo reverb return for the LCR main speakers, pan the signal inward, toward the center (See Figure 04), so that the reverb gives “shoulders” to the center channel (See Figure 05), which is good for adding a sense of space to the dialog while keeping the focus front and center.

For effects in 5.1 we often also pan the reverb return towards the rear so that some of the wash

goes to the surround speakers, tying the sound into the ambiences playing in the theater. Figure 04 again.

A sound is sent to a reverb to tie the sound into the space of the scene. The reverb returns are panned toward the source and to follow the sound if the source sound is moved. This requires a tedious multi-step process after the level, EQ, etc. of the source sound are set:

- The source sound is panned.

- The source sound is sent to the reverb’s input. The send can be panned to the inputs of a multi-channel plug-in (but this has little effect).

- The reverb output is panned to be wider than the dry signal, centered on the dry signal’s location.

So the sound and its reverb return both have to be panned. This is double the work and hard to do without errors and omissions. And since the two pan moves are directly correlated it should be possible to pan only once to get the desired results.

Pro Tools has a panning feature built into all its multi-channel sends called “Follow Main Pan” or “FMP”. See Figure 06. FMP makes the send pan exactly the same as the source sound’s pan, potentially eliminating a step in the panning of the reverbs. I say potentially because most surround reverb plug-ins take little or no note of the input pan position.

Avid’s venerable plug-in, D-Verb, which is included free with Pro Tools, does follow the panning of the send, so in this case FMP is useful. However, because D-Verb is only a mono or stereo in/out reverb, it can only be used for a “two pan” between two channels, not a “three pan” between L, C and R channels, or more. So the you still have to re-pan the reverb returns to chase the source when it pans across the screen. The reverb “shoulders” need to sweep left or right, as needed, to constantly bracket the source sound as it may move around. The localizing capability built into DVerb makes it useful for stereo music mixing, but doesn’t provide any great advantage over any other reverb for film mixing. What we want is a multichannel reverb that can algorithmically handle localization by steering its output according to the input signal’s panning, and also handle all the film style inputs and outputs like LCR, 5.0 and 7.0.

How it should work, IMHO

The main multi-channel reverbs I’ve used for film sound mixing are Avid ReVibe, AudioEase Altiverb, Waves R360 & IR360, and Flux IRCAM Verb. With the exception of Verb, and also IR360’s “eff discrete” version, the others have the problem of the output localization not following the input panning. Maybe there was a design decision to simplify the interface and internal operation of these reverbs to allow a lush and enveloping (non-localized) output effect with a minimum of user or CPU overhead.

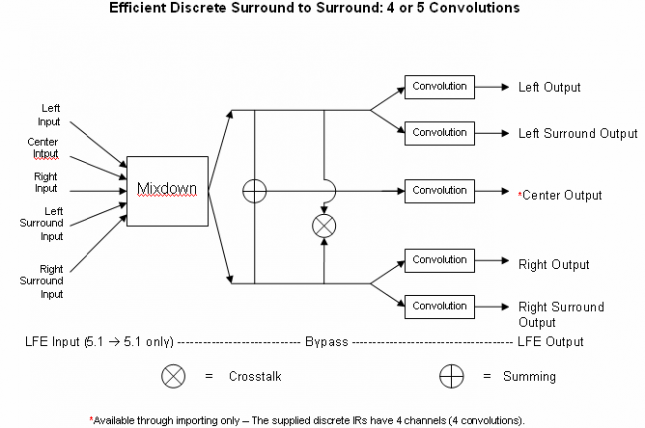

IR360 has a “sound field” version and an “eff discrete” version. The “eff discrete” 5.0 version tracks panning in quad space, with an optional center giving 5.0 out, but since “the supplied discrete IRs have 4 channels”, and I don’t have any 5 channel IRs to import, I haven’t been able to try that out. The results of using a quad IR setup in IR360 means that any sound panned to the center comes out all of L, R, Ls and Rs. Sounds panned to left or right are panned in the output to L & Ls or R & Rs only. See Figure 07. This seems less than ideal, and I’d say it does not qualify as very useful.

Verb is expensive and it has more parameters than some users like to deal with, but it allows one to turn its “Diffuseness” settings [4] down, which causes the lush all-channel reverb output to instead be more localized with the direction of the input pan. See Figure 08. This Verb feature solves the double panning problem described above. If you set up a 5.0 bus to a 5.0 Aux Input (in Pro Tools) with a 5.0 IRCAM Verb inserted and returned to your mix, you can pan your mono or stereo send to that bus and get a similarly panned reverb output. In Verb you need to have the “Diffuseness” settings for “cluster” and “reverb” turned down well below 100 for the output to follow the input’s steering.

So the ideal multi-channel reverb would allow this kind of localizing adjustment for the directional spread of early reflections and reverb. I’d love to see this feature included in the design of future reverbs from other designers. It would allow a 5.0 or 7.0 reverb to correctly follow the main pan and produce an output that emerges from the direction of the source with early reflections widening into reverb in a single process. This would dramatically improve mixing efficiency and accuracy!

Many thanks to those who read the first draft of this article and asked provocative questions and/or helped with my clumsy writing: Bernadette Glenn, Shaun Farley, Arjen van der Schoot of Audio Ease and Michael Carnes of Exponential Audio. I used their quotes with permission.

Notes from earlier in the article:

1. The speed of sound in dry air at 68°F is: 768 miles per hour (BOOM!) or 343.2 meters per second (1,126 ft/s). That’s roughly 1 foot per millisecond. Or 47 feet per frame (at 24 fps). Or 12 feet per quarter frame. Or 1.1 ms per foot.

2. See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precedence_effect

3. When keeping to the dialog to center channel convention, the Foley and sound effects for speaking characters are also kept to the center channel so that the footsteps don’t go wandering about while the voice stays in the middle.

4. From the IRCAM Verb manual:

Diffuseness

Determines the spatial width of the reverberated signal part, one could also say it changes the directional information of the reverberation, or the ability of the listener to locate the spatial origin of the signal. In a real-life space, this would corresponding to how non-symmetric, irregular and complicated the shape of the room would be.

When engaged, separate cluster and tail reverberation pushbuttons determine which section is affected by the diffuseness parameter.

A zero setting equates to maximum localization while a 100-percent setting gives full diffuseness and no localization.

The contents of this article are the property of Douglas Murray. It has been printed here with his permission. Guest contributions are always welcome here on Designing Sound. It’s one of the things that makes this site special. So, if you have an article you’d like to share with the rest of the community, contact shaun.at.designingsound.org.

Excellent article, thank you so much for sharing!

Wow! I’ve actually been wanting to try this method with music production!

god i love this site .. Shaun thanks for taking the time out to share your experience and provide such a detailed article.

Joel, please note that this was a guest contribution by Douglas Murray. He put in all the work on this particular article. Please thank him, and not me on this one. ;)

Fantastic article! Great collaborative effort and info from some of my favorite developers.

I have to say that when I first read about the issue of panning multichannel reverbs first thing that came in my mind was Ircam Verb as it’s my go to reverb.

I hadn’t had the chance to use it in a 5.0 channel mix but I do use it a lot for experimental sound design as well as natural spaces (the single algorithmic reverb that I can use for outdoor spaces).

Is there any chance there will be a followup with tips and tricks for this particular piece of coding gem?

Quick question also regarding panning stereo verbs: I’m planning on getting East West Spaces as based on what I heard is the most natural convolution based reverb.

Given that I might work in the future on multichannel mixes is there any possible ways to modify the sound with a after effect in a similar way the diffuseness parameter in Verb works?

Questin probably valid for any other non multichannel reverb out there.

On another note really excited on Michael Carnes’s personal take on “natural reverbs” as well as seeing new stuff from AudioEase.

nice article – some really interesting concepts in there.

I agree that the multichannel implementation of reverbs should be much better but at the same time we need to weigh the cost on resources against the value it adds to the overall mix.

a stereo-quad IR is gonna use twice the memory and a fair bit of extra CPU, so if it’s a choice between another reverb instance and a stereo input I think I’d usually live with mono.

Thanks everyone for the nice comments.

To be honest, I’ve only just discovered Verb while researching this article, so I don’t have any other tips and tricks to share, though I too am interested if anyone else does. And as I explore the great sounding and powerful plug-in I will share anything that seems interesting.

As for using Verb or other helpful multichannel reverbs which may require more computer cycles vs panning the outputs of a narrower reverb to allow for more instances of a reverb plugin. One of the main attractions of a localizing surround reverb that responds to the FMP feature of Pro Tools send pan is that it makes it possible to share one reverb for any number of sounds which may all be arbitrarily panned, and each will give correctly panned outputs. This can save any number of separate send busses, separately panned aux inputs with separate reverb plug-ins inserted. That can save a lot of cycles. It also saves a lot of panning efforts from the editor/mixer.

I too am very eager to see what two of the super creators in reverb design come up with next. I think there is a place in the market for more plug-ins that do what we want in post. Maybe music mixers like Cameron will be interested too!

Well the content of the article rightly states it applies to the author’s own opinions.

The diagrams describing real world direct sound and reverberant sound are only applicable under a minority of conditions. In many of the real spaces I test the reverberant field builds to a greater level than the direct field. In many locations in those spaces the direct sound is well and truly obscured and not heard at all. Even when the energy – time curve is similar to the drawings presented by the author the surface materials which generate the reflected or reverberant sound profoundly affect the tonality of the non direct sound. So don’t confuse this article with descriptions of what happens in real spaces. Even in real outdoor spaces we often hear reflected sound from approaching sources before a direct sound path is possible. I’ve measured substantial noise emissions from Truck exhaust brakes as they wend down the side of a valley where the direct sound path is totally obscured by the earth beside the road cut into the valley wall. In that case all the sound one hears is reflected or diffracted. But there can be no reverberation outdoors. Remember reverberant sound is DEFINED by lack of directional clues. The article describes the authors preference for creating sound in a fantasy world – Cinema. That’s where you are in the post production studio – a Fantasy world. That leaves you with the only tools you have to create the sort of audio experience you wish to hear. The suite of plug-ins called ‘Reverberation’ et al, are probably the only tools you have. In the case of an outdoor scene where you have an approaching or disappearing source you need a facsimile of reflected sound to come from that general direction. It’s reflected sound in the real world. You will need ‘reverberation’ because it’s the nearest thing you have but you are not simulating reverberation – you are simulating reflected and probably diffracted and even refracted sound. That really should be a separate suite of tools because you need the semi diffuse sound to be audible BEFORE the direct sound and yes – it needs to come from the general direction of the source.

Readers should also keep in mind that the general Cinema is NOT THX or Dolby certified. That means much of what goes into the surround sound mix-down created in the post production room will be severely altered by the ‘Cinema’ space in which it is replayed. Nonetheless – it pays to get it right on the track you create so at least the few people who can listen in properly designed acoustic spaces with properly designed loudspeaker systems can hear your work.

Thank you Peter Patrick for the very interesting points you raise.

These are certainly my own opinions. I am a practicing sound editor and mixer, not an acoustician or scientist. My theories about sound in the real world are based on listening, on my readings and talks with people who know more than me, on practical work mixing films, and on experimentation in the studio. It’s in the practical work that I first noticed the need to pan the “reverb” returns in order to get them to cohere with the source sound. And it was through experimentation that I discovered that none of the “5.0 reverbs” actually do what I want. I always send to stereo or even mono “reverbs” in a mix and pan the outputs, since that’s the only way to get the sound of the “reverb” plug-ins to stick to the source. As I pointed out in the article, this is a tip for sound mixing for theatrical cinematic applications. The article can be seen as a plea for a simple solution to this regular film sound workflow step of having to pan the reverb returns to achieve a coherent effect for the audience.

My diagrams are essentially copies of similar ones I have seen here:

http://www.torgny.biz/Recording%20sound_2.htm

And here:

http://www.feilding.net/sfuad/musi3012-01/html/lectures/021_environment_I.htm

I believe that the modeling of acoustic early reflections and reverberation shown in these diagrams is similar to the ray tracing models of light propagation and vision that are commonly used for VFX rendering of 3D models. It is true that only under a minority of conditions is there a shoebox shaped set of walls around the sound sour and listener. I believe it is useful as an elementary example of how sound can propagate in a space, and of the gradual diffusion of the sound.

I love your example of a truck on a valley road whose direct exhaust and brake sounds are obscured by an earthen berm, so the only sounds which reach the listener’s ears are reflected ones. And I thank you for pointing out that the sounds which I have lumped together as “reverberation” are more accurately reflected, diffracted and refracted. As you make very clear, there are many complex sonic reflections in the myriad possible environments we find ourselves in (or can imagine ourselves in). Exteriors are particularly interesting cases. Beaches, forests, fields, mountainsides, all have complex and widely spaced reflections with lots of atmospheric filtering, and are thus more difficult to use as examples in my article.

I want to make clear that “reverb” in the general sense that I have used it, and which is fairly common in sound studio work, includes the “early reflections”, and in fact includes all the sounds heard after the sound is emitted, apart from the direct sound. I also tried to make it clear that there is a more specific sense of the word reverberation “the latest reflections of sound arrive from all directions in a diffuse reverberation until the sound fades into inaudibility”.

There aren’t many sound reflection, diffraction and refraction plug-ins that I know of outside of the many “reverb” plug-ins widely available, a number of which I mention in the article. There is one exception I can think of “Orbit” by Audio Ease which models room reflections and positioning, but not more diffuse reverberations. There have been and probably are still others I can’t name. Many “reverb” plug-ins allow the user to turn down the reverberation so that the early reflections can be featured. They are still known as “reverb” plug-ins.

I’m not sure if I understand how the reflected sound can ever arrive before the direct sound. You say, “you need the semi diffuse sound to be audible BEFORE the direct sound”. I can see in your truck on valley road example how the direct sound can be obscured so that only reflected sound is heard. But it doesn’t arrive later, it is gone. Direct sound, by definition, arrives before the reflected sound. I can imagine situations where the reflected sound can be louder than the direct sound, but not earlier.

Hi Douglas,

With respect to direct and reflected sound.

Direct Sound means it has an unobstructed line of sight path from source to listener.

If I turn up the stereo in the lounge room and walk into the kitchen I can still hear the stereo and make out which song is playing.

In this case the direct sound path is so severely attenuated by walls I don’t really hear it at all – I hear reflected sound.

In some of the more challenging Houses of Worship I’ve worked in the sound from the loudspeaker is completely obscured by a huge sandstone pillar in some seats – there can be no direct sound path.

But there is a strong first reflection path where the loudspeaker sound is reflected by the side wall so as to effectively go around the pillar – a clever snooker player might get to the target by bouncing the white ball off the cush in a similar process.

In this case the listener localises the source to the reflection but it’s still reflected sound – not direct sound.

That means not only that it has traveled further than direct sound would have but also it has it’s spectral content modified by the reflection coefficients of the material it bounced off.

The point I was making really is that you really need something better than reverberation simulation models to replicate outdoor sound.

Reverberation by definition has no directional clues.

Approaching or departing sources outdoors should, IMHO, be assigned attributes related to the distance from the listener and the presence of delayed echoes. Distance attenuation would vary the frequency response in accordance with documented air attenuation. Decay time for a distant source might also increase with distance depending on the geography.

And yes again – you need to be able to pan it to the general direction of the source.

Anyhow ……

Best Regards

Great article!! I`m definitely re-reading this and warping my head around it.

What Do you think of the new Exponetial Audio Phoenix surround Verb?Did anyone try this?

Sorry to have missed your 9 month old comment. Exponential Audio has done some amazing work with the surround plug-ins. They sound great and do react to changing source placement very well and are ideal for film sound use for that reason. Since version 1.1.0 Phoenixverb Surround and R2 Surround can support linking 2 plug-ins to obtain reverb in the ceiling… 9.1 for Atmos and 13.1 for Auro 3D… all with responsiveness to the panning of the input sound. We used Phoenixverb Surround on Dawn of the Planet of the Apes for the ape vocals in particular, and I was very pleased with how it contributed to the natural spatial qualities in our Atmos mix.