This is a guest contribution coming to us from Kate Bilinski a sound designer and re-recording mixer for film, television, and podcasts. Her work includes Todd Solondz’s ‘Wiener-Dog’ and the Emmy-winning documentary, ‘We Could Be King,” as well as acclaimed podcasts, Serial and Homecoming. For this piece she sat down with broadway sound designer, composer and musician, Enrico De Trizio to discuss his unique work on No.11 Productions’ “Friends Call Me Albert”.

Perched stage-left in his own throne of sunbeams, Enrico de Trizio sets to work with around 200 knobs and buttons, while a frazzled young Einstein, surrounded by puppet companions, is struggling to decipher the physics governing the universe and how to survive university. Immersing the audience in this physicist’s world, Enrico fills the small theater with glass-like heavenly drones, bending pitches as like light and conducting sharp swells to match the motion of the floating orbs and the anxiety of the protagonist.

It’s the third and final week of Friends Call Me Albert’s run at Access Theater’s Black Box.

Enrico de Trizio is an Italian musician, composer, and producer, living and working in NYC. For the last seven years he’s been entrenched in the New York theater scene. His credits include Dear Evan Hansen (Broadway), Finding Neverland (North American tour), and Mamma Mia (North and Latin American tour). He’s worked with Tony and Grammy Award winning orchestrator Alex Lacamoire, Tony Award and Golden Globe award winning composer Justin Paul, and Tony award sound designer Clive Godwin.

However, down on Broadway just below Canal Street. I saw him working in a much more intimate setting with No.11 Productions as one of six performers on stage, wielding synthesizers and stomp boxes to tell the lesser known story of Einstein, the student and man.

Kate Bilinski: I think it’s best to start by describing your role and what you’re doing for the piece.

Enrico De Trizio: I’ve been serving as composer, sound designer and music director for No.11 since 2010. In this production in particular, I tried to bridge the gap between music and sound design. I find myself, like many others, treating those two roles more and more unitarily. It really suits the way I approach composing nowadays.

I wrote, actually more like “create”, the score and perform it live on stage every night, in addition to triggering additional sound cues, and projections.

This performance, like most of our work, really relies on music and sound so it was staged and thought out with those elements in mind, from the very beginning.

KB: So you are in from the first reading?

EDT: We develop all of our projects as an ensemble. We have regular meetings in which we decide on what to work next and we don’t really work on a piece unless everybody is excited about it. It’s during those meetings, months or years before the first reading, that the seed of a project gets planted in my head and starts slowly growing. By the time we get to the first reading, I already have something to throw in the room.

KB: Are you talking to the director in those months or is it completely isolated?

EDT: The director does reach out, maybe just to check in informally or to share some thoughts that might affect the music department. I would call him occasionally when I’m not sure on how he envisions a certain scene or a certain character but I’m very private about my work during this phase. We have been working as a group for years, there’s a mutual trust that goes beyond the usual director-producer-composer relationship. I also really value the importance of the first impression especially when I write for theater, not only for the director but also for myself and the actors. I tend to wait until everybody is in the room to let them hear the music. At that point, we should all feel if it’s right or if the direction I took needs some steering.

There is also a limit to what I can do solely at home, in my studio. I need to see the actors move. In theater, there isn’t a locked picture in which you see exactly where the cues are and how long they need to be. And on top of that, the actors keep changing and evolving their approach until they find something that satisfies them and eventually start sticking to it… and even then there’s always something happening from performance to performance that has never happened before.

But this, beside keeping me on my toes, is also beneficial to me in the developmental process. For instance, I can ask to change the timing of a scene to suit my needs. When working with commercials or films, you know how many times I tell myself, “Oh I wish this cut was just a touch longer so I could get another chord in?” Here, I can do that. I can say, “Can we stretch this so I can resolve this way?” It’s a constantly morphing process.

KB: What were the considerations when developing arrangements and sonic elements specifically for this show?

EDT: When I started approaching this project, I did a lot of research. I thought I would have been able to make a parallel between light waves and sound waves, maybe even a sonification of Einstein’s light theories. Unfortunately, this turned out to be not only very difficult but also pointless because those two phenomenons are so physically different that doing a strict sonification of what happens in the light world wouldn’t have helped the audience perceiving it. I had to go more conceptual, or “artistic” if you will, by bending pitches and playing with filters as if they were light beams. That was when I realized the sound design not only was going to be a fundamental part of the composition but it became the composition itself. I spent hours designing patches and learning how to “play” them live. We live in an interesting moment in time with this explosion of the eurorack movement. The development of the patch becomes almost the composing itself.

I was also influenced by the ensemble’s discussions. In one of our brainstorming meetings, they asked me what my favorite scientific experiment was or which was the most memorable from when I was a kid. The one that I remember vividly is the one where you have the pinwheel with all the colors on it and when you spin it, it turns white. That was my eureka moment: “Oh, let’s use white noise which is basically the same thing!” It’s a mix of sound waves containing a wide range of frequencies all blending at equal intensities. The whole last scene, that’s what it is! White noise continuously distorted through a few filters and modulators.

KB: Can you give me a rundown of everything you had on stage?

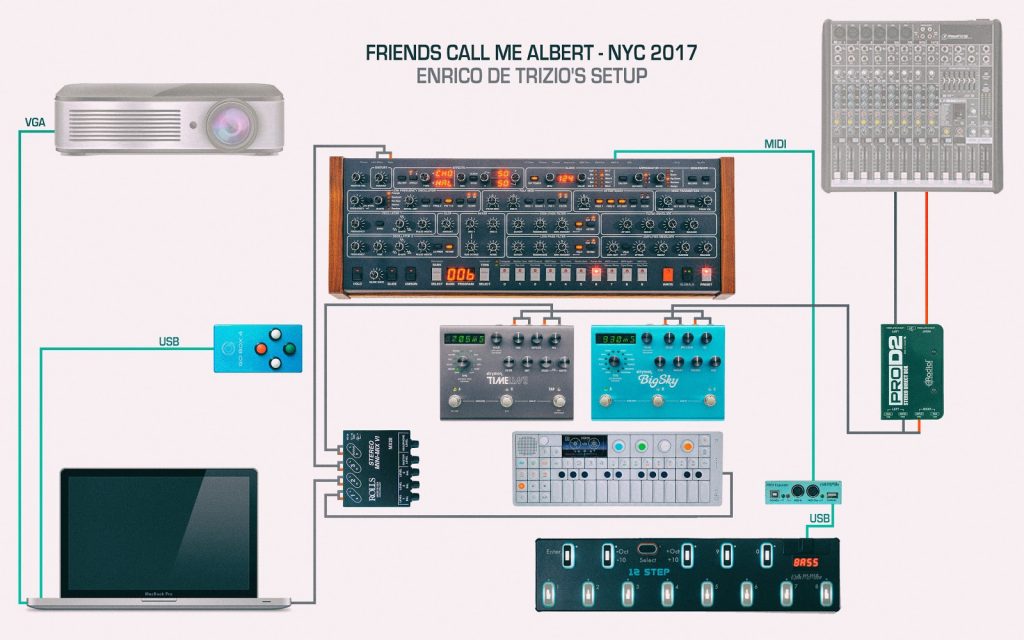

EDT: I have Ableton Live running prerecorded cues which are those dialogue bits and some Mozart pieces, as alluded to in the script. I use a little usb controller called Go Box 4 to trigger the scenes in Live. On the same machine I have QLab for the video projections slaved to Ableton Live via MIDI. Then I have an OP1 and a Prophet 6 module. All this stuff goes through a 3-channel stereo mixer (Rolls MX28) into a Strymon TimeLine pedal, and from there into a Strymon BigSky. I love those pedals, they sound great and you can be very creative with them! On the floor I have a Keith McMillen 12-Steps going into the Prophet for triggering single notes and chords. I use extensively the internal new arpeggiator of the OP1 and the internal arpeggiator and sequencer of the Prophet.

KB: So how does working with this setup vs. working with an instrument change how you approach your composition process?

EDT: One of my goals on this project was to limit myself in the harmonic possibilities and work with simple elements but still convey a sense of universal grandness. I’m a pianist, and like my teacher used to say, if you chose piano as your main instrument is because you love harmony and chords. My scores often start taking shape on the piano and then later are arranged and orchestrated for different ensembles, including electronics, which means I often end up using a lot of chords and a lot of modulations. You know: 10 fingers and 88 piano keys! Which is great but it can be overwhelming and sometimes turns against you. With this setup, I was not going to be able to do that. I have two octaves on the OP1 and one octave on the Keith McMillen 12 Step that I programmed with one patch, a mix of single notes and chords. That was it. Once that mood-scale was chosen, I was forced to focus more on the other parameters available like timbre, envelopes,and tempo. I use a lot of arpeggiators in this show and before this I would have never thought of just speeding up an arpeggiator mid-scene just to get a sense that things are running faster and thoughts are piling up on top of each other.

Also until this experiences, I didn’t realize how sensitive filters and knobs can be. A very slight movement can make a huge impact, which is especially important when somebody else is immediately responding to you. It’s not just like, “Oh well, we’ll fix that later.” Once it’s there, the actors will have to deal with it. It’s live theater!

KB: You’ve worked on many shows over the last seven years, including some large well-known productions like Mamma Mia, Finding Neverland, and Dear Evan Hansen. How is this show unique as far as your approach and preparation as well as the tasks you are responsible for?

EDT: I feel this is the most tiring performance. My thumbs hurt by the end of the night and it demands a lot of brain power because there are about two hundred knobs and buttons in front of me as opposed to the more familiar eighty eight keys plus maybe a mod wheel and a couple of pedals. But mostly because there is a lot of risk involved that normally you won’t have in bigger productions. Broadway producers necessarily have to sell a product that is consistent performance after performance and that has as little risk involved as possible. Dear Evan Hansen, for example, has a very complex metronome programmed from beginning to end so that there is no chance that one song will be faster or slower or that an accelerando will be more pronounced or a ritardando would be longer. From the point of view of the Broadway show business, once the show opens it will be consistently the same, so if you go see it today it will be just as good as going to see it tomorrow night. Or from a conductor or a music supervisor’s perspective, if a musician sends in a sub [substitute player], you won’t have to worry about flexibility with tempos and dynamics, because everything is detaily planned and controlled to begin with. On the other hand, maybe to somebody that favors a more live-experimental theater scene this consistency would ultimately lead to less spontaneity, less improvisation, less left to the musician and so on.

KB: And improvisation through your collaboration with the actors movements and mental states seemed pretty integral to this piece. How much are you preparing and how much do you take liberty during the performance?

EDT: The whole idea was to tell a story using the world of physics not only for its content but also for the aesthetic of the piece. It really feels that I’m playing with gravity when I throw a sound to the actors and they bounce it back to me in a certain way. Same thing working with those delay pedals. I flip the delay switch on and the delay starts to feedback but I have to wait for it to reach to the intensity that I want and sometimes I would love if it would to get there more quickly and sometimes slower. But that’s also part of what makes it interesting and very fun to play with. It becomes a sort of duet between me and the machines, and the machines and the actors.

The main difference between doing this kind of performance in a piece of live theater and doing it as a solo performance is that you have a commitment to the actors. You must hit the cues and be aware of their timing. You cannot just stretch things just because you are in the mood or because the night is going particularly well so you want to indulge in the moment. But at the same time, you are aware that sometimes you hit that sweet spot of the filter cutoff and it makes the noise vibrate in a specific way that you are really tempted to indulge in it. Like tonight, I started noticing the sound beating off the walls in a peculiar rhythmic pattern and I started getting into that rhythm… As I said sometimes it can be hard to keep focus and not to get too lost in “the zone”…

KB: Do you have a specific element you saw evolve as the show began to take shape?

EDT: Well, pace is definitely one of those elements because what the music does is that gives the actors another pulse besides their own. So for instance, there is that scene at the beginning where Einstein has all those existential thoughts about life, space and time. If you look at the script you think “Oh, this is a very deep, slow paced, dramatic monologue.” And maybe so it was originally in the intention of the writer, but with the introduction of music, it turned out to be quite effective as the opposite. I started playing this rhythmic pattern and Steven (Einstein) instinctively sped up and gave the text a sense of anxiety. I wanted to underline that feeling of anxiety that comes with the process of discovery, that sort of restlessness, for lack of a better word. I believe it affects scientists and artists in the same way. I certainly feel it while I’m working on a project, while I’m creating. I’m sure you know what I’m talking about and everyone who is reading this will. I really wanted to convey that with the music.

KB: So over the last three weeks, have you felt like each performance has been drastically different or can you count on certain things?

EDT: One of the things that I realized in the last few days actually is how the audience plays a big part not only in being involved in the show – laughing, crying and such – but also as physical bodies. They absorb a humongous amount of sound and that affects how the sound travels in the space. Tonight I start playing and all of a sudden I feel like there is a scoop in the frequencies and that’s just because of the audience and where they are sitting in the room. I had my volume knobs up maybe a fourth more of where they normally are just because most of the audience was sitting in the back.

KB: I was actually the only one in the first row…

EDT: For some reason, nobody wanted to sit in the first row and that really affected the way I was hearing the sound and mixing.

In addition to that, the actors are variables. They might have worked all day so one night they may talk quieter. Or one other night they may talk louder and then the next night, one actor is very loud and the others are very quiet… you got the picture, it can get surprisingly complex.

KB: I assume this a unique experience for you to be actually on stage.

EDT: Yes, I would say it’s rare. When you sit in a Broadway theater, you rarely see the orchestra. Sometimes they are hidden in the pit. Sometimes they aren’t even in the theater! They are in another building because of lack of space and they are cabled into the theater. And because the music is so precise, you may not even realize that there are nine… eighteen… twenty four players playing. So I’m trying to push as much as I can for productions to give a little bit more visibility to the musicians and value live music as a vital part of the show. For this show, you wouldn’t know that all that stuff was made live, if you weren’t seeing it. And people aren’t used to it either. In our first review, the writer thought that I was some kind of technician inexplicably on stage. And I see why you would think that. I purposely didn’t want to bring a keyboard – I just wanted knobs and buttons to articulate the piece. When people think of a composer or a musician they still imagine somebody with a violin, a guitar or sitting behind a piano. They don’t realize how much of today’s music production makes a large use of those other tools. These machines are musical instruments too in all respects, they make sounds… beautiful ones.

Thanks to Kate for putting this interview together and to Enrico for taking the time to answer her questions. You can learn more about Kate and her work at katebilinskisound.com. We also interviewed her earlier this year which you can check out here. You can find out more about Enrico and his work at enricodetrizio.com and you can find him on twitter @enricodetrizio.