Guest Contribution by Jeff Talman

Seong Moy, my drawing professor at City College of New York, had students lightly shade their sketchpads with hand-smeared charcoal to prepare a background for the drawing. This neutral background helped to create an illusory sense of depth in a 2-dimensional medium. The negative space of the drawing was activated by this treatment. Had there been no shading, no defined background, the objects in the drawing would not have existed anywhere, but would have been only representations, floating and free of context. The background helped to create a space in which to work.

Similarly, audio engineers know how important the background silence is in recording. In the early days of Audio CDs engineers learned that absolute silence between tracks created a void that the listener could find to be unpleasant, as if the CD was somehow unnatural because it did not exist in any space itself. The problem was compounded in that LPs had a consistent background sound. So sound on the early CDs seemed to ‘drop out’ between tracks. Soon engineers added low levels of ambient, background sound to fill these voids just as the charcoal smears did for the drawings.

Ask a mother whose children are suspiciously too quiet: something is wrong. Absolute silence is unnatural. John Cage famously found that to be the case, because even an anechoic chamber exposes the background sounds of one’s own body. In typical human terms, silence, no sound, is simply impossible to experience. The notion of silence then takes on the reality of low level background sound, what we call ‘silence.’

Most any post-production engineer will deal with matching room tone, the ‘silence’ of the space in which dialogue occurs, so that post-production dialogue is suitably placed in the correct visual space in the film. Here we have a very specific reference to human ‘silence,’ the nothingness that is not nothingness.

There is also a perfect example in microcosm of the interstitial nature of background silence that is consequential to the foreground sound: audio engineers dither audio by adding low-level noise to a signal to avoid zippering effects as audio fades in or out. This dithering noise cannot be heard in the sound program and so is, in effect, silent. But its effects are anything but silent. We can hear the direct result of an application of ‘silence’ to what would otherwise be unnatural sounding fades.

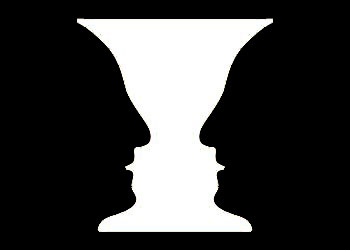

You have probably seen instances of optical illusions that are capable of dual interpretation, for instance a vase that turns into two faces. Illusions of this nature are dependent on the relationship of the object and the ground.

When one looks at the central white mass the outlines of an object, a vase, are easily seen. But when looking at the interior black edges, it’s possible to see the outlines of two faces. When the image is interpreted as a vase, the ground is black. When silhouettes of faces are perceived the ground is white. To see both images the viewer must shuttle between which is object and which ground.

To the sound designer the audio program is the object. The room tone, i.e. silence, is the background. Normally background levels are ambient only. Should too much background be forthcoming then the recording is noisy and the program material is compromised as our attention is diverted to the annoying, too-loud background.

This ambient sound takes on even more meaning when it’s necessary to establish a place or an event by some specific background sounds, for example music in a bar, train sounds inside a train car, or the wind, rain and waves during a storm at sea. The background, not an ambient silence, now functions in creating a strong sense of place.

However, this background-producing, strong sense of place is available in subtler instances, for example in a large reverberant space. In a cathedral you will notice that so-called silence is actually an ambience that involves a slight thrumming, a sonic spatial characteristic unique to the space, as might be illustrated by spectrographic analysis (see image).

When a choir sings in a cathedral it’s as foreground to this ambience. The ambience is similar to the negative space of a drawing. The ambience is ground; the choir is object. But they are not isolated from one another; they interact as the acoustic space modifies any program sound occurring there.

This ambient ground is the negative space of sound or “negative sound,” to be further activated by other sonic event. So rather than thinking of non-program sound as a kind of idealized silence I prefer to think of it as contributing to the definition of the program sound while also defining the space from which it arises — silence, as it turns out, is active.

As the student smeared the charcoal to create a sense of place in the drawing, so the sound designer has a palette of ambiences available to create a sense of place that frames the object sound. Visual artists make use of backgrounds to give definition to the objects they render. So it is with negative sound. But visual artists might make ambiguous the foreground and background such that they exchange roles. This is just as true of object sound and negative sound.

Which brings me to a quote from visual artist Robert Irwin, “To be an artist is not a matter of paintings or objects at all. What we are really dealing with is our state of consciousness and the shape of our perception.”

Regarding sound my question became, “What do we perceive in these silences?” Nearly two decades ago while living in Prague I visited St. Vitus Cathedral many times to listen to the sound of the space. With practice I began to hear the acoustic imprint of the space. I believed I could hear ephemeral resonance in the space that offered a very slight glow of harmonic organization. This was later borne out by spectrographic analysis. In the low level, thrumming ambience — the “silence” — of the cathedral there is unique and extraordinary harmonic activity.

Slight wind and thermal currents in a space produce these resonant sounds just as the air blown into a bottle will produce specific frequencies resonant to the bottle. In search of these ephemeral sounds I’ve made recordings of the ambience in more than one hundred European cathedrals and churches in order to analyze their acoustic signatures.

Realizing that background might become foreground, ground become object, I’ve culled resonant frequencies from spatial recordings of so-called silent spaces (they are never silent). Using these as materials for composition I’ve then created sound installations that are presented in the space from which the resonant frequencies were produced. These become feedback loops in which the original harmonic resonance of the space is re-resonated by the space. The background becomes foreground as a composed, multichannel program, but this object sound also recedes into the background from which it came. As program sounds fade in and out it may become impossible to tell which is installation sound and which spatial sound — as they contain the same elements. The installations teach me to better hear the space itself.

Further, the installations offer a unification of object/ground toward an increased sensitivity to spatial interpretation for the listener. In my estimation a much greater sense of presence, of human spatial awareness, and the perception of self in relation to space becomes available even as a distinct otherness pervades. The other is the human self in the sonic environment as created by the self-sound of the space. True, there is interpenetration as the sound enters, and may even resonate, the body in unpredictable ways, creating a kind of continuum. But there is a flux between this bodily reaction and the sense of otherness or opposition to space. So body/space may exhibit a blending of object/ground but also may be in stark contrast to each other as one’s situational awareness is engaged by spatial resonance feedback.

Likely we are instinctively aware of space via its sound, but the amplification and reintroduction of spatial sound characteristics makes readily available this seldom examined facet of our sensual interpretation of a place. As this sense comes forward, and as the flux between object/ground operates both in sound/negative sound and body/space, metaphoric values may apply. Silence may imply nothingness, oblivion, lifelessness, death, rest, peace or otherwise — but note there is no true silence. Importantly, the notion of an internal or meditative journey as reaction to a heightened sense of sound and physical space applies. The arising sense of an inner space ideally would be congruent to the internalized sound and the initiating physical reality of the external soundspace.

Importantly, sound and space are dependent on each other. Further, they both suggest and are dependent on time. Even the voids of outer space carry the thirteen-point-eight billion year old imprint of the Big Bang, a sound. But then the voids of space on which sound is borne are not voids. They are the negative space, the negative stuff, the negative sound, no less than the air we breathe, the counter to and on which the object sounds of the world sound and resound.

The Negative Space of Sound, © 2014 by Jeff Talman

Jeff Talman has created installations for Rothko Chapel, Cathedral Square in Cologne, the MIT Media Lab, Eyebeam, The Kitchen, bitforms, the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Villa Croce in Genoa, St, James Cathedral in Chicago, St. Paul’s Chapel at Columbia University, NYC and numerous museums, galleries and alternative sites including four Bavarian Forest installations. Talman’s work has been featured on Nation Public Radio, national German television and in the New York Times, The International Herald Tribune, Wired Magazine and many other publications.

Cited by Oxford University research group Intute as a ‘pioneer of the use of resonance in artworks,’ Talman’s installations investigate the nature of sound and other primal wave forces (light, gravity, the sea) and their effects in generating concepts of natural and architectural space, human presence, place and time. Awards include Guggenheim Foundation and New York Foundation for the Arts fellowships and artist residencies internationally.

Talman was born in Pennsylvania (USA) where he studied piano. Further studies in music and visual arts led to orchestral directorships at Columbia University and the City College of New York and other teaching positions at the Massachusetts College of Art and Emerson College. Moments From The Sun, his third CD, will be released later in 2014. Jeff Talman lives and works in New York City.

For more information see www.jefftalman.com and www.vimeo.com/jefftalman

Terrific piece, Jeff! Off the top of my head, two film sound designers who have used “ambient” sounds to great effect are Alan Splet and Ren Klyce. It can be argued that the sounds we “don’t pay attention to” as audience members can penetrate us even more deeply than the sounds we attend consciously. I suspect our brains are trained through evolution to subconsciously monitor the periphery, especially for signs of danger; and “periphery” probably includes the moments we “think” are silent, but are not.

Thanks Randy, much appreciated. I agree with you that our brains probably are subconsciously in touch with these background sounds. A problem is that urban life is filled with too much chaos, so in self-defense we shut down the connection with the background. On the other hand modern architecture seeks to quell noise by acoustic damping. But by doing so it diminishes our sonic sense of space so that, in essence, we can’t hear where we are. I’d like to see architecture that was sonically smarter, but beyond film sound has the potential to return a sense of reality that’s not in the reality!

Really enjoyed reading this. It got me thinking about the level of silence many people live with in and around their homes and how it is generally accepted. What would happen if you took the level of road noise that people near a city are used to, but played it to them out of context in say an anechoic chamber, that would quickly become unacceptable I would think.

In addition to “Slight wind and thermal currents” can we rule out traffic vibrations and other such intrusive sounds?

I’m not sure how you mean ‘rule out’ Dave. If it’s in regard to resonance, then intrusive sounds may or may not play a part, but it’s usually only intermittent (and so not the ambience of the space itself).

Resonance operates on continuity of sound frequency/energy (as with a constant wind that activated resonant frequencies of the bridge in the famous 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-zczJXSxnw

Intrusive or intermittent sounds can trigger resonance, can even help you hear the resonance of a very quiet space better as spatial overtones will pop out if activated. But the ambience of the space is ambience – a continual backwash of resonant activity based in the air motion of the space and the architecture.

Some spaces have that constancy fed by other wide frequency bandwidths that can trigger resonance, like the sea or a constant rain or climate control. Other frequency-specific intrusions might be constant but not activate the space, such as electrical hums.

I had the opportunity twice to make recordings in the Cathedral of Cologne, Germany between 3-6AM. On both occasions I had the sexton turn off all power in the space – and so had the place entirely free of tourists, traffic and noise in the town square outside – it was as silent as the place could become. There were a few trains that arrived in the nearby station and as 6 AM approached more and more street noise. On one evening it rained part of the time. But one night it was very clear and very, very quiet.

Even in the ultra-quiet it could not have been anywhere else – I could hear it.

Perhaps ‘rule out’ wasn’t the best choice of words, but such things as traffic are pretty ubiquitous these days and you made no mention of it. Also traffic generates a very low frequency sound that travels very well and couples with architecture effectively. These low freq vibrations are sure to create higher freq tones that would be involved in the sound of the ambient space.

Then too, when we talk of the very low dB levels of the ambience of quiet spaces, perhaps the self noise and resonance of the mic/stand can contribute as well. I worked at a studio where we had a problem on one session when we’d rented a bunch of very good mics to record a small orchestra and when they were all on, only then could we hear the rumble of the trucks on the street. Still, it was there.

In a related scenario I was in Joshua Tree National Park on a quiet afternoon and I could hear a fly buzz 50′ away and a jet high overhead echoed for 5 minutes. Nothing is ever silent.

I’d love to hear some of these as you describe.

Hey Jeff! I got this article a plug since I thought it a worthwhile read.

http://urbansurvival.com/coping-from-the-cynics-notebook/

Best regards.