When I saw/heard Gravity last year it set me of on an exploration of dialogue panning to such an extent that I experimented with some fairly extreme panning in the film I was working on at the time. My experiment proved to be, well, inconclusive at best. So I went back to Gravity to see just how the panning worked within the context of the film, then decided to look beyond it and discovered some interesting dialogue panning going on in Cars (2006) and Strange Days (1995) as well.

I started my analysis from the premise that dialogue generally finds itself nailed to the centre speaker for the vast majority of a film’s running time. This is as much a technological fait accompli as an aesthetic choice, in no small part due to the introduction of the 5.1 speaker standard where the centre channel seemed perfectly configured to take the dialogue load, freeing up the remaining speakers to be exploited for music and FX. From this posit the sound in Gravity is a serious departure from a standard approach to mixing film sound, but also a well reasoned one.

Even before seeing the film we were treated to a sneak peak behind the scenes courtesy of the Soundworks Collection, complete with a nifty little graphic at about 5.30 showing us the extent to which panning was being employed in the mix.

[vimeo]http://www.vimeo.com/76123849[/vimeo]

Only when I saw the film (sadly only in 5.1, the nearest Atmos equipped screen being nearly 3 hours away by train!) did I understand how this seemingly haphazard approach to panning was not only integrated into, but also driven by the films narrative. The first thing to note is the film’s attempt to be entirely scientifically accurate i.e. there is no sound in space. Given the extent to which the film takes place in the literal vacuum there was always going to be some concessions made with the soundtrack. Music goes some way to filling the void, featuring heavily in the surround speakers, most noticeably during the action beats. The FX that we do hear are to a large extent, contact mic recordings, delivering a muffled, non specific representation of some of the actions we see on screen, highlighting that sound transmission is only possible through physical contact with objects. This means there is considerable latitude for the film’s dialogue track to orbit the cinema.

Right from the word go the soundtrack drifts towards us from the right speaker, gradually revealing Stone (Bullock) and Kowalski (Clooney) and introducing us to the fact that for this film at least, the dialogue is not going to be tied to the centre. The nature of the dialogue goes some way towards normalising us to the panning, given that for almost all the external sequences we are hearing futzed, radio transmissions, which by their nature imply a certain sense of dislocation. Juxtaposing this tight, claustrophobic dialogue with the stunning opening shots, all wide vistas, also lets us as an audience settle into the panning device. When the camera finally settles on a two shot of Ryan and Kowalski we are at home with the radio interview-esque nature of the panning, hard left and right.

The first big action set piece is clearly where Skip Lievsay and his team reached for their panning joysticks, very likely with no small amount of glee. The music ramps up and the dialogue sets off on a merry journey through the surrounds. As the sequence develops and Ryan begins to drift away the placement of the dialogue gives us clear positional information, serving to increase our sense of distance and also clue us into what part of the inky blackness we should be focusing on next.

At one key point in the narrative, where Kowalski unhooks himself from the tether to save Ryan, the film actually subverts it’s own device, abandoning the dialogue panning despite the clear opportunity to do so. Here the aesthetics of the sound mix bows to the demands of the narrative. The intense nature of the dialogue exchange trumps the desire to move it around and here at least, the dialogue reverts to the centre.

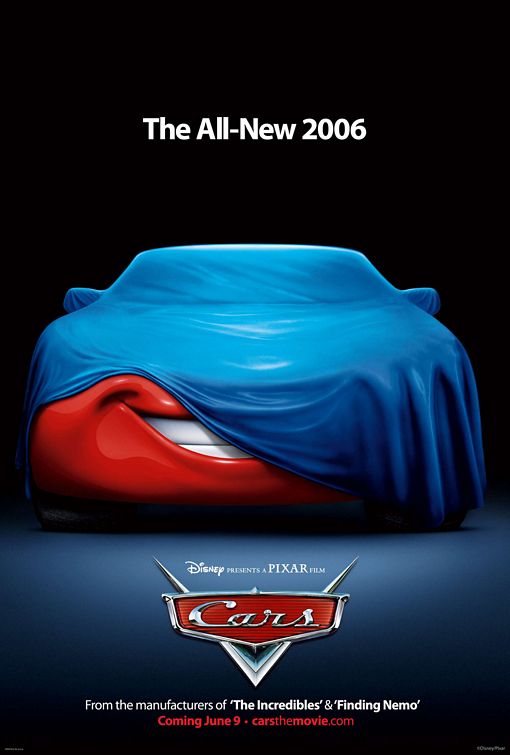

While nowhere nearly as extreme as Gravity, Cars also makes use of dialogue panning to enhance the narrative. However, keeping in step with Gravity, it does so as a direct result of the film’s narrative, rather than on a whim. The simple fact that we are dealing with cars and not human protagonists, somewhat frees the restraints on dialogue movement, something that is true of a lot of Pixar’s animated output.

In Cars the pans are, in the main, smooth and sweeping, following characters as the either move past static cameras, or enter or leave shots. A good example occurs during the court scene where Doc Hudson moves right to left across two static shots and his dialogue follows. Another example occurring later in the film finds Mater and Lightning entering a scene from behind the camera, placing their dialogue in the surround speakers and shifting perspective with the camera.

In the case of Cars at least the dialogue panning works because of the nature of the characters. We are well used to the panning of car engines as they move across, or out of, the cameras field of view. To not pan the dialogue associated with these engine sounds would likely disconcert the audience in a whole new way. It also treats it’s panned dialogue with appropriate equalisation to highlight the of axis nature of the delivery, something that the radio transmissions in Gravity are by their very nature lacking and perhaps the one aspect of the films mix which grates just a little.

Strange Days approaches dialogue panning in a completely different way, though here again it is driven by the narrative. The film features a device known as SQUID, which allows a person to record any experience from their own point of view (to what looks like a mini-disc of all things) which can then be played back by someone else, allowing them to re-live the experience as if they were there themselves. The nature of this plot device opened the door for the sound team to experiment with their placement and panning.

The films opening sequence, which runs for some 4 minutes, is entirely POV, giving plenty of leeway to place us, the audience, right in the centre of the action and making the camera an active component of the scene, not just an omniscient viewer. This kind of sound treatment will be readily familiar to FPS gamers (at least those who game in surround) but in 1995 it was only possible to experience the full effect of this sound experiment in cinemas or via AC3 encoded laser discs, which were few and far between at the time. The sheer kinetic nature of the sequence in question, a robbery and subsequent getaway, is heightened by the scattered nature of the sound mix. Dialogue comes at you from all sides (as do effects for that matter) but all the while it is clearly intelligible and supportive of the scenes visuals.

While these three films approach dialogue panning in very different ways, they do so as a response to the narrative. They also all share a distinct lack of what we would consider to be traditional Foley, particularly in those moments where the dialogue is being panned. By it’s very nature Gravity is essentially devoid of Foley (contact FX aside) so it is not exposed to the quandary often faced when considering panning dialogue; should I also pan the Foley? Cars likewise is essentially Foley free. I’m willing to accept an argument that the nature of the film means the engine and wheel noise takes the place of Foley, but as are already programmed to expect engine sounds to pan in a mix, it doesn’t get in the way of dialogue movement. In Strange Days there’s plenty of Foley but given the POV nature of the camera, the placement of the Foley is entirely perspective dependent, freeing up the panning of the dialogue from this apparent constraint.

I’ll leave the last word on this to Gary Rydstrom, sound designer and re-recording mixer on Strange Days.

We hear 360 degrees, we are always hearing 360 degrees so whay shouldn’t movies reflect that reality when it’s dramatically appropriate?

Quote from “The Dolby Era: Film Sound in Contemporary Hollywood” By Gianluca Sergi

This is a nice article. Thanks Cormac.

I love well panned dialog, but it’s a rare thing. The big 70mm road show movies of the ’60s played with dialog panning but the films weren’t designed for that and it turns out that the ping ponging of the dialog on reverse angle cuts, especially with the huge, wide screens, is disturbing for an audience. Dialog works very well when anchored to the center.

As you point out, we need some kind of ‘excuse’ to pry it off the center speaker. In Gravity it’s the lack of gravity or spatial anchor. Cars has our experience with panned car sounds to lean on. And for Strange Days it’s getting into the subjective POV of a very intense experience. Once freed from the center, the dialog helps place the viewer into the immersive space of the film, and even into the head of the protagonist.

Interesting indeed. Working predominantly in Imax since 1995, we’ve been panning all dialogue as long as I’ve been involved. Granted they were mostly documentaries, but the screen is 80ft wide, so having the narration up the centre is expected, but spec fx and voices in the bg are always screen specific. Some of the more dramatic 70mm films have benefitted from panning the dial, but only in so much as it wasn’t distracting – then panning was cheated so there was some directionality, but it wasn’t violent.

Hey Douglas

glad you like the article. Good excuse for watching some cool films. Need to get on the hunt for some more.

cheers

You could see Cloverfield which is a POV film, supposedly captured during an attack on Manhattan by a large monster by an amateur camcorder operator. I personally panned every isolated mic channel and ADR line individually to follow that character’s movement in the space of the film. All the Foley and other sound effects are panned and rotated as appropriate to create a fully immersive experience. It’s pretty cool, if I do say so myself.

The film in its 5.1/7.1 form is a wonderful mix (and excellent Dolby demo), mixed at WB’s De Lane Lea facility by the talented Skip Lievsay (note spelling) and Niv Adiri. Glenn Freemantle (Oscar nominee for Slumdog Millionare) provided Sound Design and Steven Price’s very clever score, which does so much of the heavy lifting. Some tweaks were made at Pinewood afterwards a few months later and the first scene had been horizontally flipped). The Atmos mix took place at the WB Burbank facility. In the interim, some greater understanding of what wild and wonderful things they could do with the sound had been refined. The results are to be witnessed in an event of a movie that facilitated such a great opportunity for a wild and wonderful marraige of sound and picture. If you can see it in Dolby Atmos, every minute of travel is worth it. Also the first film I have seen where they max 3D and you do not need a bottle of Aspirin.

Nice article Cormac :) I totally agree with your points here. Every sound we place in a film and every elements we mix and process has to be done to support the film’s characters, story and overall style of the movie. These films (at least Gravity and Strange Day as I’ve not seen Cars) fully justify the free panning of dialogue as they suit the style and shape of the films they are used in. I remember loving the use of panning and placement of sounds in Hurt Locker for the same reason…playing FX in the surrounds and panning dialogue at times here also caused the audience to move their head around a bit looking out for the sounds in the same way as the soldiers entering unknown territory were also scanning the surroundings everytime they heard suspicious sounds. Cool writeup!

I wonder if Skip and his team mixed with 3d glasses on…

Though I can see it’s artistic merit I wonder how much extreme panning degrades the experience of those watching in less than ideal positions in the auditorium? The predominate use of the centre channel for dialogue, and largely the reason for it’s existence, was to make sure the whole audience could here the words.

Indeed in the analogue days being able to tweak centre was a life saver when showing films mixed in perfect conditions by people who knew all the words when the actual cinema had average acoustics, ventilation rumbling away, sweet wrappers rustling etc.

…bollocks. Hear.

You are right, Rob. It takes a certain amount of smearing of the sound to spread it across more than one speaker to make it sound good for all in the room. On Cloverfield, I used a plug-in called ARL Sound Stage (which is no longer supported, sadly) to spread the sound across the LCR speakers, and adding some time related manipulation to the panned sounds (similar to the way HRTF creates the binaural effect) to give a precedence effect to the source channel, while not fully eliminating the sound from the center speaker. This really helps preserve the stereo image for everyone in the theater. It would be nice if there were a reliable multichannel plug-in that could do this today in AAX. perhaps SPAT will do the trick, I’ve just made a mental note to play with that.

I might be mistaken, but I believe that the ISOSONO panning plug in is supposed to take the precedence effect into consideration. I haven’t used it much though.

Randall

Fitting a Cloverfield viewing into my schedule Douglas, thanks for the pointer. Got me wondering about the POV sequence in DOOM as well? Can’t remember if it took the opportunity to pan or not?

Regarding the sound smearing I seem to remember using one of the older Dolby Pro Logic processors to help spread mono signals but I doubt it was as sophisticated as the ARL plug-in. Pity it’s no longer supported.