Rob Bridgett is no stranger to us here at Designing Sound. Constantly writing and engaging in community discussion; Rob has put out a new book called “Game Audio Culture“. Here are some questions Damian Kastbauer and I put together for Rob.

Can you tell the few Designing Sound readers who don’t know who you are a bit about your background in sound design, game development and book authoring?

Hi, i’m an audio director based in Canada. I’ve been lucky enough to work on audio for games for around 14 years. I’ve never really thought about it until you asked me this question but writing is a really important part of the audio design process for me. It helps me to understand/document what just happened and what will happen next, so i’ve been doing that for almost as long as I have been working.

What is your new book about? Why did you decide to do it?

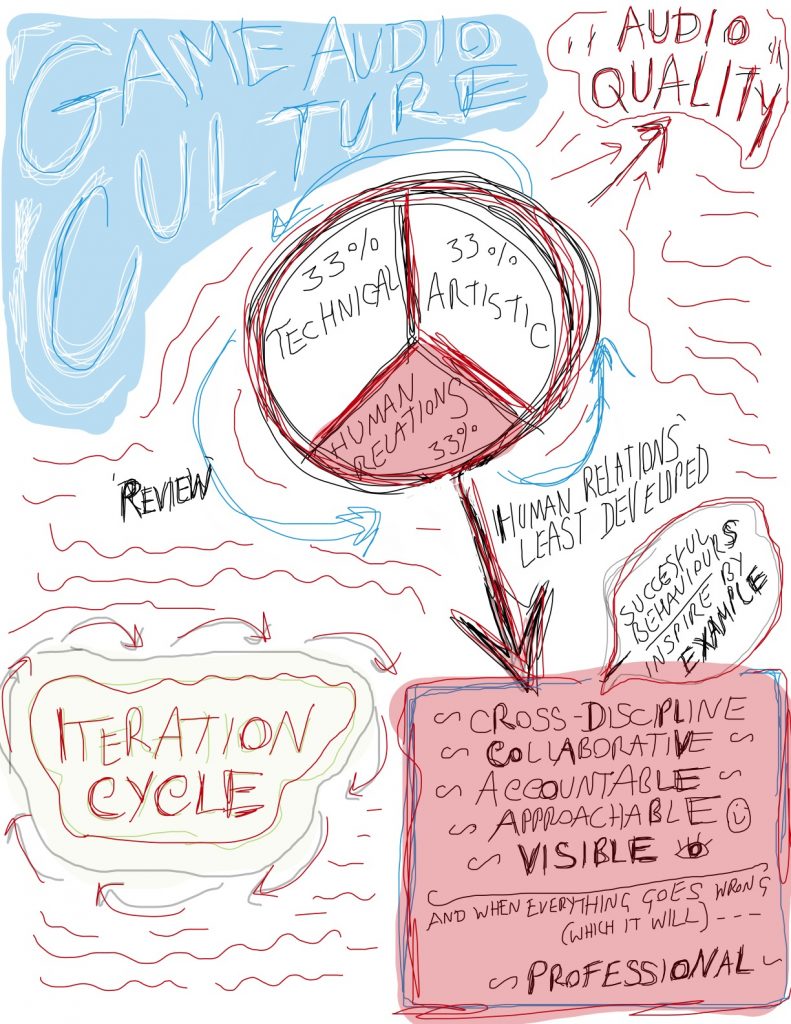

Overall, the general umbrella of the book is about how sound designers work collaboratively, but also how fundamental collaboration is to sound design. It deals with areas where sound still needs to get under the skin of design and production and some of the opportunities i’ve seen over the years that are available to do this. It feels like we are at a tipping point in terms of how the industry as a whole approaches sound, there are a lot of changes happening both in terms of how we think about and where we work with sound, and even what is considered as ‘sound work’. The book is written from my own perspective as a sound designer / audio director – and as someone who has seen both A3 and indie/mobile development and sometimes how segregated the disciplines can become – there are so many exciting opportunities right now to re-invent the way games are made – sound collaboration is right there at the centre of some amazing new innovative game experiences – Honestly, and this is the reason I wanted to write this book, I am more excited right now than I ever have been about the industry. We’ve been through a lot of changes over the last few years, and with a multi-discipline approach it feels like those changes and innovations are just the beginning – the capacity for change and innovation seem like the only constants. A lot of people have been saying this for a while, but now you can really see it happening!

To help better integrate the audio team; you have a design for a sound studio in the middle of a dev area with triple-glazed glass with a 360 view which looks like the cats pajamas. Did you come up with the design yourself? Are there any working versions of something similar?

Yes, it is a studio design that would allow people to see in and out of the room at the same time as having it soundproofed and acoustically treated, so it would be an architectural challenge to realize this design. It would be inside the team-space – not on a separate floor or tucked into a corner. I think a 360 degree view for people inside and out is the most important part of the design. The reason for this is about feeling included and connected to the team, and the team would be able to see the sound people inside at work, connecting the team to the sound and demystifying the work. Natural light is also a consideration here, but the main thing is the lines of connection to the team. I think this can be done in any number of ways. I saw a similar design principle at Crytek recently where they have windows that look through several walls so you can see all the way through to each sound suite, although this was not in the team space, it had a similar collaborative vibe.

How necessary do you feel specialized sound proof rooms are to the daily job of a sound designer on-site? Do they cause more harm that good?

They are useful for certain parts of production, they are essential for others, and they are harmful for others. The way I look at this is, if collaboration and openness is at the heart of the values and the culture of the studio, if it is part of the DNA of the team, then this has to be reflected in the spaces that the team works in. Flexibility is essential, the space needs to change and adapt quickly to fast changing team activities. As a member of a sound team, I’ve seen first-hand the positive and negative side of many of these different ways of working – working on headphones in a team space – being comfortable in a collaborative team space environment – having beautiful purpose-built soundproofed pods and studios – No matter how well intentioned you are, out of sight is out of mind, and sound suffers from neglect, not through anyone’s conscious fault, but because of a fundamental invisibility of sound to the rest of the team – this silently kills collaboration before it can even begin.

So, what damage could be done by a sound designer locking themselves away in a room away from the rest of the team? Does film have the same problems regarding the separation of sound and production?

I think with film, directors and producers might be more comfortable coming into those studio spaces, there is a difference there, it is subtle, but significant and worth mentioning. Cabin fever in the studio is the behavior that leads to the separation of sound and production on a game team. Also, a lot of sound designers and directors I know are introvert leaders, and having an extended physical disconnection from a team can be very negative for this kind of leader – It results in retreat and can even lead to avoidance of social interaction with the rest of the team and, at worst, a sound team can feel like outsiders with their own sub-culture. The best thing a sound designer, director or team can do in this situation is to simply be aware of this and to treat it with regular daily or even hourly contact with the team where possible – lunches, hourly coffee breaks in the team space, whatever works and whatever it takes. The amount of information that you simply absorb from being around the team is almost absurd to miss out on. You also absorb and contribute to the culture, which is critical if you are going to want to positively influence the culture of sound in the studio, you need to influence the culture of the studio.

When Randy Thom suggests that “early involvement is the single most important factor that allows you as a sound designer to do something interesting and truly useful in terms of storytelling on a film.” Do you feel that in games it is easier to do something useful and interesting because most of the sound departments (usual) involvement from the start?

It should be easier for us in games to get this right. In studios that have in-house audio, we are physically in the building and on the team when the early work on projects is happening. Some of my biggest challenges have been getting invited to and even being aware of those meetings. There is still a reluctance to involve sound because it is viewed as a ‘production’ element, and not a pre-production/conceptual element. The way i’ve often been able to solve this is to sell the sound department, at a high-level, as ‘another art department’ – this just helps the perception, and when you do get a seat at the table, to make sure you contribute and don’t waste the opportunity. Not having a seat at that table leads to all kinds of issues later on down the road. Randy is very clear and eloquent about the potential successes and failures in the process for film – politically film is a very different beast to games – but essentially it is the same creative process in that any idea can be influenced and improved by the involvement of a multi-discipline team. That doesn’t mean sound needs to become the director of that experience, but it does need to be a contributing member of that early incubation team (in Randy’s words a ‘Principle Collaborator’). Iteration of a game idea starts way before a single line of code is written, it starts in those early dinner / lunch / watercooler conversations / meetings and on those white boards – perhaps the biggest, most fundamental decisions are happening at that early stage.

If the future includes more freelance, more per-project contracting, and more collaboration, where are the consistency, benefits, and ecosystems to support work-for-hire specialists providing a temporary service? Do we need one?

I do see sound contract collaborators being brought into small teams earlier, especially in the 2 – 3 person studios developing some really iterative/innovative mobile games. The degree to how embedded they are depends on the culture, and most crucially, on the trust between the collaborators – it may take two or three projects together for the team to gain the trust vibe that is necessary to make it happen the way Randy Thom describes working with Bob Zemeckis for example. There we are seeing a career-long collaboration going on, in a very similar way to how Ren Klyce works with David Fincher. I see contracts working well on that level, you can’t just show up and expect to start working with someone’s most cherished ideas from day one. This is something you need to nurture long-term – I think that the relationship between sound, art and design is only as strong as the relationship between the sound designer the artist and the designer. I see the in-house audio director as often fundamental in promoting this kind of outside-in collaboration and bringing contractors into some of the bigger projects – you can get way more value out of a trusted contract sound implementer than just ‘sound implementation during production’ – if you bring them in early enough, they can influence the pipeline and the process for the benefit of everyone – in many cases they are the ones using tools and pipelines that have been created by someone else, maybe someone who isn’t even with the company any more, and bringing them in even a little earlier is going to be a huge benefit there – they also bring a ton of outside experience you can leverage for your team as well as inspiration / fresh eyes-ears. I think the cases for bringing composers in earlier has been well made elsewhere; composers are a social and vocal community who have been championing this cause for a while now – it is the same deal though, becoming trusted collaborators. How do you do that? You start by making contacts, being professional when an opportunity arises, working hard and being curious about the ideas you are working with – then I think you build those relationships naturally. I guess as a contractor you get to work with many different people, companies and leadership styles, so you have a unique viewpoint on the industry – that can be a very useful asset. For me, I love working with contractors because it means I can choose a trusted team wherever I am working, I also love putting people together and meeting new people with new ideas.

You provide a lot of suggestions for ways to increase collaboration/ communication between disciplines. Are there some teams that are doing it right?

Sure. The teams that I see doing this well are also innovation leaders in the industry, and I don’t see this as a coincidence. It is in the DNA at DICE and Naughty Dog – there are a great many companies doing ‘sound as design’ really well, for example Play Dead and ThatGameCompany. Simogo have popped up on the radar pretty recently in this respect too – the experience they create weaves in sound so well. Having fully integrated multi-dimensional design is absolutely a huge part of the success of these teams, I think it comes down to every team member thinking multi-dimensionally, not just sound teams.

On a similar note, I want to say that it is really hard to change a culture, but it is possible, it requires a massive political effort and co-ordination across disciplines. It may require a change in culture and DNA, which can be a massive shift, and sometimes a painful transition for an organization to make. Those that are able to make these changes, and survive, are very very exciting places to be. I guess what I am suggesting in the book is to start this process if it doesn’t exist, push harder for it if it is in progress, and keep doing it if it is already in place.

It’s fair to say the book is written from the in-house audio perspective, more than it is on say, a contractor delivering all of the audio content. For contractors: is there any advice you can give to help them include “design thinking” to a project/client when they might not have as much organization pull or even a say in any scheduling?

It is always a call you have to make as a contractor – are you comfortable enough in your client relationship to suggest changes in areas other than sound (with the goal of improving the experience)? It totally depends on the nature of that relationship, and the trust, going both ways. Although I think that if suggestions of this nature are made professionally, and wherever possible directly (preferably in-person rather than email or phone) then as a contractor you shouldn’t be afraid to push a little further in that direction – I guess the key to these kinds of collaborations is framing comments as a suggestion – and I suppose thinking about how you like to receive suggestions will help to frame anything that you might suggest to the client – but there are always things that you are not privy to as a contractor, and this incomplete picture makes it more difficult to gauge. There’s no harm in testing the waters, and it is a relationship building activity, so i’d recommend it – you could very likely be helping the client make decisions. As long as you speak honestly and professionally. The best book i’ve read on this (clients and contractor work) is still ‘How to be a Graphic Designer Without Losing Your Soul’ by Adrian Shaughnessy.

In your book you mention that we need to stop saying “audio is 50% of the experience” which I totally agree with. Do you think this mindset has a negative impact on working with other members of the development team?

In a collaborative production environment, this kind of statement is disrespectful to art (all departments from animation to environment), design, tech, production and pretty much everyone else on the team who isn’t in the sound department. If you are in a non-collaborative space, then this statement and thinking thrives because you are using it to fight for that involvement. Honestly, I think this quote, in context, was a good attempt at shining a spotlight on sound and how much a part of the experience it is for the audience (“sound is 50% of the movie-going experience”). A director using the phrase comes from a place of pride, when a sound designer uses it, it comes from a place of frustration. What it has become, unfortunately, is a defensive power-grab position which sound designers on the back-foot use more often than they need to. Some of the rhetorical uses of this statement i’ve heard are to try to get more budget for sound, which again, is likely to backfire because anyone hearing this will assume you want 50% of the production budget. To me sound designers using it show a lack of confidence in sound’s role, it feels like a statement that is impossible to qualify – i mean, can you really quantify the contribution of the many many components of an experience? But, I don’t know, perhaps it is still a useful phrase for people selling hi-fi equipment?

What can we expect next?

In terms of writing, a project i’m really excited about is a book of interviews with sound designers, audio directors, composers, producers, dialogue directors etc who I really look up to and am inspired by. I’m thinking it will be something good to do next GDC, on the fringes of the event itself – coffee shops, bars etc :D – these are some of the places i’ve had the most amazing conversations – it would be awesome to be able to capture some of that by recording and then typing-up later. It is a different kind of collaboration, but fundamentally a part of that same bigger picture of making better games and participating fully in the wider industry.

You can buy Game Audio Culture online here. Be sure to follow Rob Bridgett on Twitter.

[…] https://designingsound.org/2013/09/interview-rob-bridgett-and-game-audio-culture/ . […]