As a sound designer, there are many different thoughts that come to mind when considering a topic such as noise. Everything from using tone generated noise, like white noise in the designing of sound effects, to a technical discussion on different types of dither algorithms, but when I kept thinking about noise, one slightly different viewpoint of the word “noise” kept coming back to mind; like attempting to attenuate something that just won’t go away, this question kept creeping back into the forefront of my mind:

How does a sound designer get their “signal” heard through the ever-increasing amount of “noise” that surrounds us (and our intended audience)?

There are many detractors that can cloud our sonic message, starting with the growing number of media streams/content (most with their own sounds and many times multiple media streams playing back simultaneously), coupled with the loudness of the inherent ambient noise of the busy world around us, which is only heightened by the ability to experience media content in almost any environment imaginable, even while flying (just don’t turn on your mobile device during taxi, take-off, or landing). And then there is one more obstacle to consider: with the influx of produced and distributed media content, many times for free, (a double-sided byproduct of the lowered “cost of entry” into the audio arts, due to DAW’s increasing depth and power, yet simplified user experience and reduced financial investment), how do we even get our sounds to the ears and heard by our intended audience at all?

These questions led me to start to think about a few audio professionals, teams, applications, and content that I believe start to show a path towards getting (or keeping) your signal heard over all of this noise. As loud and clear as possible.

Bit Depth and “The Devil’s in the Details”

A high signal to noise ratio, or dynamic range helps our ability to suppress the interfering frequencies that if heard, will distract our audience from the audio content that is intended to be their focus. Though more directly, bit depth determines how loud something can be captured (or played back) before the introduction of noise (simplified a bit to make a point, the science is a bit more involved), for instance: a 16-bit recording introduces audible noise into the signal at an amplitude of 96dB (-96dB to 0dB), and then with a 24-bit recording, noise only becomes audible at 144dB (-144dB to 0dB). This is an impressive difference, as traditionally, we calibrate our monitors to around 85dB for a film audio mix, and as long as the movie theater projectionist follows instructions in regards to the audio playback settings, the movie’s audio should fall around that range (though often times this can vary +/- 5dB or more depending on each theater and/or projectionist). Sound decibel levels become dangerous right around this level as well, so for extended playback, I cannot imagine we will ever consider pushing past 90dB and expecting our audience to have a pleasurable (and safe) listening experience. This means that presumably 16-bit audio can playback without audible interference comfortably in almost any scenario, though when we go to 24-bit audio, we push this to 144db, and initially, this may seem completely unnecessary, but what this added dynamic range provides for is better clarity in the reproduction of our quietest sounds and retains the nuances and subtlety within our content (such as the natural decay of a sound effect that may be lost below the noise floor at a lower bit depth).

The saying, “the devil’s in the details” holds very true in sound design. Subtlety and nuance is integral to deriving the deepest emotional impact from our audience. For instance, during our analog days, just placing any sound to picture required quite a bit of technical skill (and access to equipment), though now this is relatively easy to accomplish for anyone, with or without a background in the art and science of audio production. This means as professionals and artists, we must continue to produce more nuanced and emotionally engaging content, or our intended sonic message will surely get lost among the “noise”.

One way to add effective, yet nuanced sound to a project is by examining and taking into account the deeper meaning that a scene (or project) is attempting to convey. During a recent Tonebenders podcast, Coll Anderson (credits) spoke about understanding character motivations, personalities, and emotional context of each moment in a film (among other aspects) in order to design the most emotionally impactful sound(s) for the film as a whole. As already mentioned, virtually anyone can place sounds in a timeline and make a gun shot sound playback when a gun is fired (for example) on camera, but a true sound designer must look deeper, and aim to covertly and subtly direct the emotions of the audience. By knowing the context and “raison d’être” of a scene, a sound designer is able to create an audio soundscape that doesn’t just place sounds where they need to be in a film, but has a much deeper impact and can serve to dramatically increase the effectiveness of a scene, and a film (or other form of multimedia) as a whole. This is the type of thinking that can lead to the use of subtle, yet extremely effective and emotionally engaging sound design that will give your signal deeper meaning, and will keep your work in the forefront of the minds of the director and other creative production staff when the next project comes along.

Fully exploring the context of a scene, the motivations and personalities of each character with the director (and other integral creatives on a project) before designing sounds for their actions and environments as Coll Anderson does may only alter our sound design thought process slightly, but in the end, it will be those small sonic details, those nuanced sound elements that subconsciously have the greatest emotional impact on our audience. As sound designers working in visual media formats (such as film, video games, etc), our responsibility is to give that final emotional push that only audio can provide; in essence, to finish the job that the visual elements started and fulfill their emotional potential.

Though understanding a character’s personality (for instance) is vital to producing the depth and emotionally compelling sound(s) for that character’s actions, that information about the project’s story must be coupled with at least a fundamental knowledge of psychoacoustics, or the physiological impact sound has on a listener in order to produce truly effective sound design. Sound and its properties; such as tempo, timbre, articulation, dynamics, etc. all have a substantial impact on a listener’s emotional state and we should be aware of how manipulating these properties will affect our audience. This does not mean that in order to be an effective sound designer, a true sculptor of sonic experiences with emotional depth, we should consciously and constantly think about the timbre or articulation of a sound as we work; this would be counterproductive to the creative process. Though by studying and understanding how sound affects us and allowing that knowledge to seep into our design methodology, along with (on a project by project basis) exploring the characters’ motivations, scene context, and so on, we will innately feel and react during our design process to what a specific project or moment in a project needs audio-wise in order for it to be most effective.

Denoise and Finding Clarity

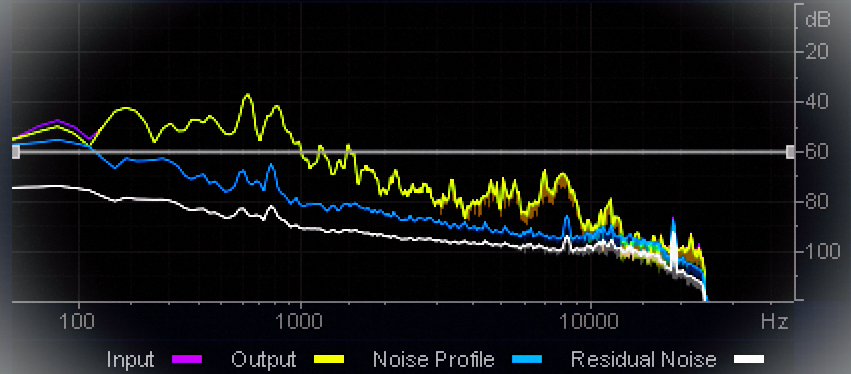

As mentioned earlier, a high signal to noise ratio helps our ability to remove those interfering frequencies (the noise) that distract our audience from the audio content that we want them to hear. Many times, if we must work with a noisy audio file in a project (such as dialogue we cannot redo through ADR for one reason or another), we will turn to the use of denoising software that allow us to sample a selection of noise, have the application “learn” the noise frequencies, and then use that frequency “map”, our own parameters, and the application’s equalization algorithm(s) to audibly reduce these unwanted frequencies. This is the goal of denoising software such as Waves’ Z-Noise or iZotope’s RX (This hyperlink is to an in-depth review of RX 2 by Varun Nair), to separate the signal from the noise, and then suppress the noise, while attempting to leave the signal we want heard as intact as possible. With both something like Z-Noise and RX, the noise is captured and then used as a threshold that will allow frequencies that are louder than the set noise threshold to pass through virtually unaffected, though if your signal is too similar to the noise (in amplitude, as well as frequency content) in the audio file, it will get attenuated along with the noise.

As sound designers looking to get our audio heard, like denoising applications, we must also find ways to separate our signal from all of the noise that is around us, both metaphorically and also in a more literal, physical sense. Metaphorically, if our creative audio output or design aesthetic is too similar to what people are used to hearing from other sound designers, the sounds you provide will blend in with, or become part of the collective “noise” that people are more and more trained to ignore. It is important to learn from other sound designers and their techniques, but it is even more important to develop our own sonic voice (or style) as a sound designer or the value of our contributions to this art form will always be extremely limited. In a literal sense, these days, we may be called to design audio for playback through mobile devices, casino slot machines, televisions/home stereos, theaters, theme parks, and even airplanes (to name just a few). Each environment and delivery system will inherently have its own noise profile and we should adapt our thinking accordingly whenever possible.

Nice article, thanks a lot.

Martin

Glad you enjoyed it, Martin. Thanks for reading.

interesting article- the one thing I would warn on though is that the notion of their being an absoute 144db dynamic range in a 24bit audio file is a bit misleading- we have two principle things to consider in that- the first, is that no one can really take in, without damaging their bodies a sound of that amplitude, and second, there are no microphones or preamp electronics or speaker systems which can give that sort of playback performance. Im most cases we work in a dynamic range window of about 80db and most film and television programs have an effective dynamic range of about 30 db…

Thanks Charles, and I am glad you found the article interesting. By no means did I intend to mislead anyone into thinking that we could (or would want to) record or playback anything at 144db; we are already putting our audience at risk with current playback levels. To clarify, my point was that recording and working with audio at a higher bit depth provides the ability to capture and reproduce the quiet sonic details that would potentially be lost due to the raised noise floor of a lower bit depth. I was using bit depth and it’s direct relationship to dynamic range, but more in a general manner (and in a much more theortical manner than a practical one). Though for anyone that wants a much more in-depth look at bit depth, and really digital audio (which was not the intended focus for this article), there are many more technical discussions on the subject, and specifically, I would recommend this recent Monty Montgomery’s article: http://xiph.org/~xiphmont/demo/neil-young.html

thanks for the link, I had already read that, and found similar problems in the assumptions the article was based, on- it is a fine commentary on end product usefulness, but doesn’t take into account the benefits of high resolution on the input side of the process. I know I can clearly hear the difference in 96k vs 48k audio, even with microphones with limited bandwidth. And I prefer to be able to work with the best raw materials possible if I have a choice in the matter.

This is true and I agree with you. The article I mentioned is based upon end user playback, though there is a brief mention of the value of working at a higher bit depth during audio production. With an area such as digital audio, there are going to be perceptual and individual differences of opinion and preferences in the way that we record, process and reproduce audio for our audience (which was not a direction I wanted to go in with my article). I don’t know that one article or viewpoint will suffice everyone in regards to this topic, though I feel he provides some good points to think about (Monty’s article). Really, it is about experimentation on a personal level in regards to what sample rate/bit depth we each want to work in and is appropriate for our specific media application and workflow. I’ve worked at a few different sample rates and bit depths as technology has improved (obviously, you have as well), and I personally do believe that a higher bit depth will provide us the ability to capture audio content that otherwise may be lost or at the least compromised by being too close to (or below) the noise floor. Thanks again for your interest and taking the time to comment. I am definitely interested in hearing more of your thoughts (and practical experiences) regarding digital audio recording, processing, and reproduction. I hope this conversation continues, either here on this post, or in a future article (or feel free to email me directly as well if you would like).

actually re-reading the article, I will reverse my comments- I disagree mostly with it, especially the claims of 24 bit audio having no value over 16 bit.

With 24 bit vs 16 bit (as I wrote in my last comment), I completely agree with you. I do believe there is value in recording and working at 24 bit (for the clarity and potential reproduction of low amplitude sounds, though not to reproduce audio at 144db… just to be clear once again). I believe he tried to take any subjectivity out of the article and look at it solely in a scientific manner, though in practice, and practical application, I definitely agree with you regarding bit depth and the value of working at a higher bit depth if you are able.

Really enjoyed this article, definitely given me a new outlook on Signal to Noise Ratio!

Thanks

Rob

Thanks Rob. Really glad you enjoyed it.