Guest contribution by Andy Farnell

Images by Jemima Yong

This article is the first of two part series on two sound symposia that recently happened in the UK.

The Theatre Sound Colloquium – June 28 2013

First off, the last days of June. The sun finally came out in the UK in time for a splendid Glastonbury Festival, and I was in London for the Theatre Sound Colloquium held at at the prestigious Lyttleton Theatre on London’s South Bank. Perhaps a stage set for Maxim Gorky’s play ‘Children of the Sun’ was a fitting background for rumblings of disaffection and revolutionary plotting on theatre technology. The tactic of provocateurs Gareth Fry and Donato Wharton certainly paid off, inviting participants from backgrounds as wide as cognitive neuroscience and musical stage management into the fray. This masterstroke by the organising bodies of The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama and relatively new British organisation, the Association of Sound Designers, lit the sparky fuse on the black-ball comedy bomb of events. The outcome was an explosion of ideas, a wonderful day enjoyed by all with some passionate discussion on future sound technologies.

First up was a presentation by eminent auditory neuroscientists Prof. Andrew King and Dr. Jennifer Bizley on audio-visual correspondence, scene analysis, proximity effect and temporal acuity. Why is this important to stage sound design? It goes right to the heart of technical and artistic problems encountered in live work that simply do not exist in film post production, radio or game sound. Here the space and audience are traditionally seen as part of a complex system that are immutable constraints, but one observation that King and Bizley added to the mix was that beyond the physical and perceptual characteristics of

performance spaces we usually associate with such work as that of Beranek and Sabine, the human auditory apparatus is quite adaptable. In short, there is a lot the

audience can get quickly tuned into, so long as it is consistent and properly signalled.

What followed was a vibrant discussion on the possibilities and limitations of live sound reinforcement for theatre, decorrelation effects, issues in multi-channel reinforcement, and fold-back monitoring. I was reminded of the importance of teaching this subject and the possible value even to script writers and directors of considering the perceptual situation of audiences and actors. These drops set in motion the first flows of waters running beneath the whole symposium, of the need to maintain, and in some cases re-appropriate technology as an integrated and empowering part of the artistic project, rather than capitulating to technical complexity and assuming technique must dominate rather than enhance performance possibilities.

Next came an enjoyable and challenging presentation by Dr Jonathan Burston on the scaling and replication of productions to the international stage. A similar theme arose, of tension between the impossibility of such events without technology, the changing aesthetic of performances driven by technology, and the dehumanising price to be paid in this bargain. Risk aversion associated with uniform replication of the Disneyfied “Mega Musical” can turn actors and singers into automatons. It seemed to me a great deal could be relearned from the studio producers’ ethos (perhaps typified by Albini) of bringing out the best in artists without enslavement to technique, and cultivation of facilitating attitudes in directors and crews who as Anthony Horder reminded us, have a “duty to the audience and to the actors”.

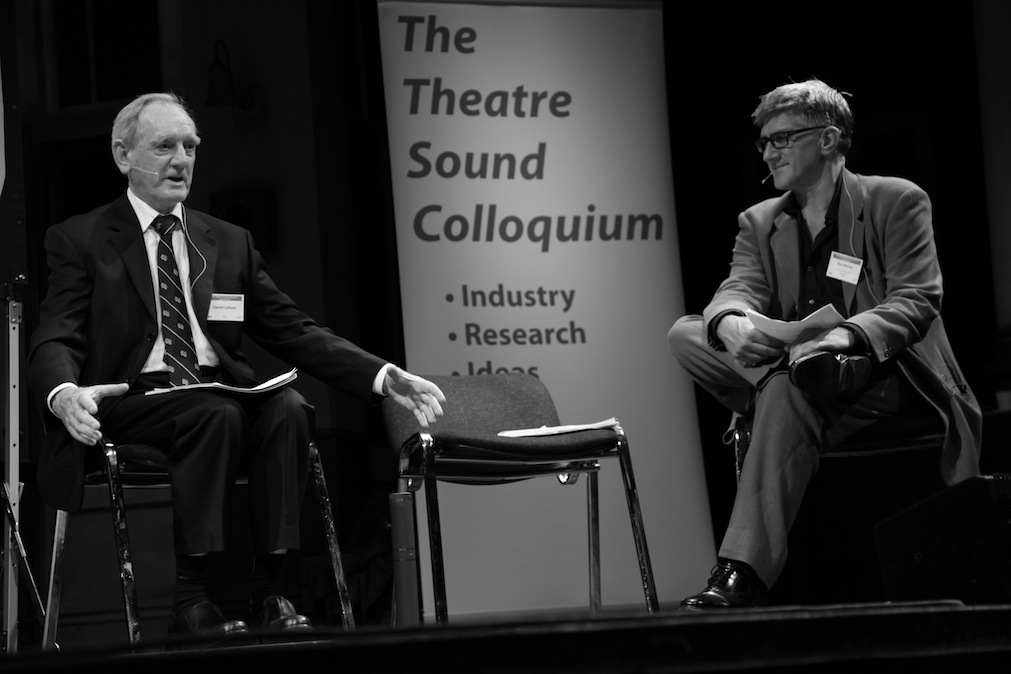

To best unfold the story I will mention that one highlight of the day for me was the presentation of David Collison with honorary fellowship of the RCSSD. Collison, the first credited “sound designer” (noting that theatre sound design predates film by some time), whose career goes back to 1955, has been responsible for many innovations in sound design, including the introduction of sophisticated reinforcement and mixing techniques into theatre. Modestly describing himself as unschooled and opportunistic Collison epitomises the confident, independently creative, open minded, pioneer who leads where industry and money follow. He is what we today would call a hacker, a person with a sense of innovative and interpretive agency, mastery and enthusiasm.

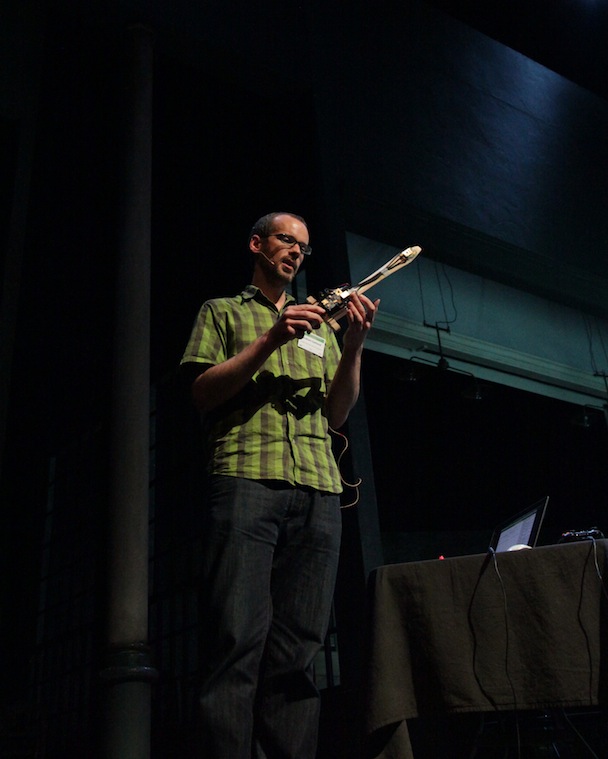

Next enter Graham Gatheral, whose presentation really made my day. Graham gave a presentation on the elementary principles and advantages of procedural audio, first in a game development context using demonstrations of some rigid body, fluid and fantasy weapon models activated from Unreal UDK via an OSC socket, and then moving to a broader discussion of performance driven models. He demonstrated stage props with embedded signal processing technology such as a sword containing gyro-accelerometer sensors to generate parameters for `swoosh’ sound synthesis.

Graham’s talk was exciting for me not just because of his heroic battle with the Demo Gods, which descended into impromptu live Supercollider coding (with him successfully rebuilding his presentation in front of a crowd), nor because Graham, not a student of mine, is an independent adherent of procedural audio with

his own slants and interpretations, but because the presentation seemed so very warmly received. Something I maybe did not expect. Being accustomed to cool responses to procedural audio from the game industry, it was great to see uncomplicated, hospitable and enthusiastic acceptance.

Theatre is the birthplace of sound design. Where there is a sense of play and expression there is a willingness to incorporate and interpret. Indeed the response to Graham’s talk was positively invigorating. Possibilities in the renaissance of maker technology, embedded SBCs, amateur electronics, interactive and installed

systems in the arts bode very well for bringing reactive sound models to the stage and other live performance spaces.

Key to this is the recognition amongst stage managers, directors, actors and artists, of a need to retake more direct forms of control over performance technology.

Procedural audio in a live context offers great scope for expression with movement, dance, speech and active stage props. Rehearsal and performance are enriched where the sound stage designer can offer interactive capabilities to performers, instead of searching through libraries for categorised and defined forms. It can help provide a common ground of gestural behaviour instead of mediating ideas through potentially clashing aesthetic and technical vocabularies.

Reflecting on the colloquium I was reminded by Varun Nair of the success of innovative businesses that find their way “pivoting to an alternate market”, and that Amaury La Burthe of Audio-Gaming had expressed some surprise at getting more business out of the post-production industry than gaming. Maybe this makes sense since film is driven more by content than it’s tool chain, and theatre even more so.

The antagonism between convention and invention, in old Marxian terms, is the interplay of innovation versus labour value. Put simply, creative industries can end up paying their most creative individuals not to be too creative, but keep using the same old approaches and become interchangeable modules in the machinery of expedient but pedestrian output. That’s how we get mass production and lots of new jobs, but the down side is a dampening of creativity.

Anticipating and adapting to cultural and technological trends is something big media needs to work at. As far back as 2008 content developers were sitting up and smelling the demise of the old recording industry. I write as 120,000 people sit in the Glastonbury sunshine. The live event and human interaction are back in ascendency, with the market growing at about ten percent per annum over the past five years.

I notice a significant shift in interest toward real-time interactive AV performance amongst students and researchers. This is giving fresh energy to musical performance and dance. Certainly new transducer options such as cheap gravitational and IR depth of field sensors in commodity products like Wii, iPhone and Kinect have played a part, but I also sense an underlying cultural reaction to packaged media forms. While there are stirrings from startup manufacturers such as the ROLI Seaboard, an army of tinkerers and independent inventors are picking up their Raspberry Pi and Beagle boards and retaking the open and potentially contentious ground of user the defined interface. Could it be that procedural sound technology finds a strong foothold not in its apparently natural habitat of sophisticated mediated arts like computer games and CGI movies, but first builds a strong forward base in the theatre and live arena where a different mentality towards the utility of technology and empowering forms of expression exists?

Concluding this part, the Theatre Sound Colloquium proved a great forum for exchanging ideas on sound design technologies in the live arts. An interesting mix of psychology, design and practice left me with that fresh feeling of possibility that smaller eclectic gatherings accommodate. I felt those assembled took to risky conversation with ease, openly and eloquently questioning their technology and processes. It was also a success for the Association of Sound Designers. Lets hope there is more to come and a growing body that serves sound design professionals and amateurs in the UK.

Andy Farnell – a familiar name in computer audio – is a computer scientist, sound designer, author and a pioneer in the field of procedural audio. He is a visiting professor at several European universities and the author of the bible on procedural sound – Designing Sound.

Related: An Interview with Andy Farnell , A Quick Introduction to SuperCollider by Graham Gatheral

[…] This article is the second of two part series on two sound symposia that recently happened in the UK. Part one is here. […]