By: Karen Collins *note: some excerpts from this section are taken from my book, Playing with Sound (MIT Press, 2013).

Music and sound design are often treated as separate disciplines. We describe ourselves as composers or sound designers, get hired to do one or the other (usually) and awards are given to these jobs as separate categories. It’s rare that sound design gets taught in schools, but when it does, it’s more likely to be a component of film studies than music departments. But are music and sound design so easily separated? Famed film sound designer Walter Murch (2005) argues, “Most sound effects… fall mid-way [between music and noise]: like ‘sound-centaurs,’ they are half language, half music.” In fact, some of the most interesting music, films and games are those that blur the distinction between the two.

What is often referred to as “non-musical sound”, or sound effects (including percussion) wasn’t used in Western music for centuries. In Medieval Christianity, percussion was said to signal the presence of Satan, and wasn’t used in any Church music. What was acceptable to the Church was what was used in music, and so non-tonal sounds were typically ignored. In Noise Water Meat, Douglas Kahn argues that, “Within the history of Western art music, noises were not intrinsically extramusical; they were simply the sounds music could not use. Their determination of extramusicality rested not in a hard and fast materiality but in the power of musical practice and discourse to negotiate which sonorous materials will be incorporated from a world of sounds, including the sounds of its own making, and how” (1999, p. 68). Perhaps due in part to the particularities of the Medieval Christian idea of music, the use of sound effects was seen as a distinct discipline from music until the arrival of the 20th century avant-garde.

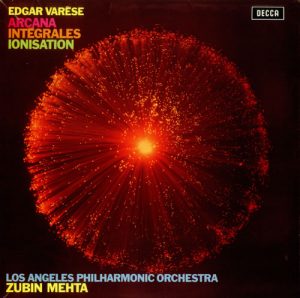

With the advent of recording technologies and electronic instruments, the sonic palette of musicians was widened. Early electronic music, such as that of Edgard Varèse, had experimented with recorded sounds as early as 1924-5, with works like “Intégrales”. Varèse’s “Déserts” was written using tape-recorded sounds in 1954, one of the first musique concrète pieces, a new genre of music that was defined by the use of sound effects. Influenced by the works of John Cage (who himself cited the influence of Luigi Russolo’s Art of Noises and Henry Cowell’s New Musical Resources), Pierre Schaeffer’s first musique concrète recording, “Étude aux chemins de fer” used a collage of steam trains with changes in speed and backwards masking.

It is, however, perhaps through the science fiction cinema of the 1950s and early 1960s that many more popular music artists may have heard non-musical sounds used in music for the first time, where mechanical and electronic sounds had been used to represent the future, the alien, and in particular became associated with many of the rationalization narratives of Red Scare anti-communist sci-fi cinema. Predating many of the experimental synthesizer sounds of 1960s and 70s were pioneers like Delia Derbyshire (“Doctor Who”, 1963), Louis and Bebe Barron (“Forbidden Planet”, 1956), Harry Lubin (“One Step Beyond”, 1959), and Bernard Herrmann (“The Day the Earth Stood Still”, 1951).

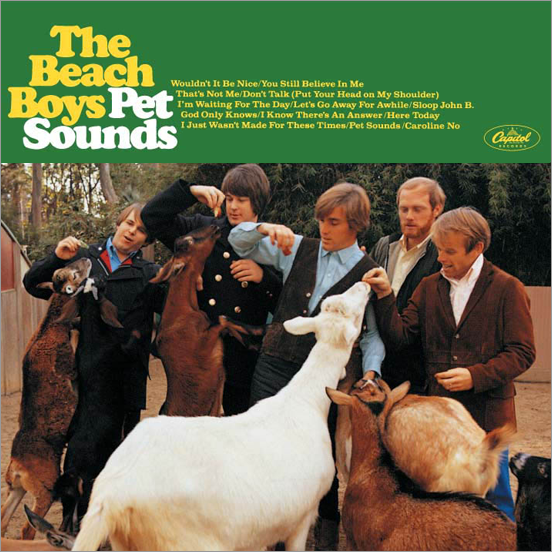

The techniques of the avant-garde—and of science fiction cinema—soon showed up in popular music, where bands had been playing with the use of cut-up tape techniques, non-musical sound and electronic experimentation, including the Beach Boys (Pet Sounds), and the Beatles, with their Revolver album of 1966 and 1967’s Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

It’s not surprising that many films that blur the distinction between music and sound design tend to be from the science fiction or horror genres. The alien (and often futuristic) nature of the worlds created is often reflected in the underscore, which may try to be disconcerting and unfamiliar in order to unsettle its audience. The more abstract the music, the more it becomes a kind of ambient soundscape rather than a coherent “song” in the traditional sense. Even more than that, it can be downright scary to have the fictional world blur into the “real” world: music is usually outside the fictional (diegetic) world, but sound effects are typically contained in that world. Blur the distinction, and you blur reality with fiction. Notable examples of sound design and music crossing into each other in sci-fi and horror film include Chu Ishikawa’s score for Tetsuo: The Iron Man, Jerry Goldsmith’s Planet of the Apes, Schifrin’s THX1138 and Alan Splet’s Eraserhead.

It’s not just science fiction and horror film that blur sound design and music, of course. Skip Lievsay and Craig Berkey describe using wind as music in No Country for Old Men, for example, where Berkey states, “To me the winds were the score throughout this part of the film” (https://designingsound.org/2007/11/no-country-for-old-men-exclusive-interview-with-sound-designerre-recording-mixer-craig-berkey/). And most video games could be argued to blur the distinction between sound and music, since throughout video game history, sound effects have often been tonal, and synthesized with the same sound chips found in music synthesizers of the 1980s.

Video games—often situated in alien worlds and the unfamiliar—have been an ideal medium for crossing over between music and sound due to the technology, the narrative, and the interaction of the player. The overall sonic texture of games can often create an interesting interplay between music and sound effects that blurs the distinction. There are certainly examples of games where we might question whether what we are hearing is sound effects, voice, ambience or music, such as in the Quake or Silent Hill series.

In a sense, sound design in some genres of games is closer to slapstick and cartoons than it is to more traditional Hollywood film, with music more closely tied to action, rhythm and movement, and with stylized sounds that are often not intended to be realistic. The music of Scott Bradley for MGM cartoons in the 1930s, for instance, integrated musical sound effects directly into the composition, blurring the line between sound effects and music. Daniel Goldmark (2005, p. 51) writes, “Perhaps [Bradley] realized that [sound effects] were ubiquitous not just because of popular convention but because they were integral to the cartoon soundtrack. Bradley seems to have incorporated as many sound effects as possible into his scores and thereby controlled, at least occasionally, the balance between two of the three elements of the soundtrack [effects, music and dialogue]. Such musically based sound effects frequently made unnecessary the common device of a separate non-musical sound effect to double or supplement the action in question.” Indeed, “Mickey-Mousing”, as the process of closely aligning graphic action and sound events has come to be called, became famous in cartoons—imagine the footstep sounds of characters as they walk up and down stairs being timed with notes going up or down. The technique was, in fact, used in several early games, such as Dig Dug and Looney Tunes: Desert Demolition.

In some games, the sound effects and music are so closely linked that they are integrated together, quantizing events to the musical beat, such as in Mushroom Men, described by their composer:

Ok, so there’s these bees in one of the levels, and we made a track that was the theme for the bees that was like [sings/buzzes theme]. We tied this into the bees particle effect so that its [sic] in sync with the… [buzzes like a raver bee]. So yeah, the bees are buzzing on beat, which I thought was really fun. Actually, every ambience in the whole game is rhythmic… wood creaks and crickets and all the insects you hear which are making a beat, and every single localised and spatialized emitter based ambient sounds are on beat too (see Kastbauer 2011).

Dialog can likewise be used in a textural or melodic way. There are many examples of Nintendo games that treat voice as sound effect, for instance, where a pitched sound is repeated according to the number of syllables in the accompanying written text, such as in Mario and Luigi: Bowser’s Inside Story. In this game, low-pitched sounds are associated with larger characters (e.g. Bowser) and high-pitched sounds are associated with smaller characters (e.g. Starlow), while Mario and Luigi themselves speak in a gibberish Italian.

So what does this all mean? Well, it goes without saying that sound designers should be talking to composers about what kind of integration between sound and music will take place. Are there sounds that can be drawn into the underscore? Are there musical motifs that can be drawn into the fictional world (such as tied to particular game events)? What frequency bands are occupying the most acoustic space? Can ambience be used in a musical, tonal or rhythmic way, or can the music be used in an ambient, textural way? It’s not surprising that many films and games that win awards for sound have a very careful integration between sound and music. That push-pull between reality and the fictional world that can be created is powerful and emotionally moving.

Watching and listening list

Dead Space (Electronic Arts 2008)

Dead Space 2 (Electronic Arts 2011)

Mushroom Men (Red Fly 2008)

New Super Mario Bros (Nintendo 2006)

Quake (id 1996)

Quake II (id 1997)

Silent Hill (Konami 1999)

Dig Dug (Namco 1982)

Planet of the Apes. (F. J. Schaffner) 1968. 20th Century Fox

Tetsuo: The Iron Man. (S. Tsukamoto) 1989. Kaijyu Theatre

Texas Chainsaw Massacre. (T. Hooper) 1974. Bryanston

THX1138 (G. Lucas) 1971. American Zoetrope.

Eraserhead (D. Lynch) 1977. Libra Films

No Country for Old Men (Coen Bros). 2007 Paramount

Edgard Varèse Intégrales for wind and percussion (1924–1925), Ionisation for 13 percussion players (1929–1931) Poème électronique for electronic tape (1957–1958)

Pierre Schaeffer: Cinq études de bruits (1948), Etude aux objets (1959), Nocturne aux chemins de fer (1959)

Delia Derbyshire: Dr. Who

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (1955–56)

Louis and Bebe Barron (“Forbidden Planet”, 1956)

Harry Lubin (“One Step Beyond”, 1959)

Bernard Herrmann (“The Day the Earth Stood Still”, 1951).

Beatles, Revolver (1966) and Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

Beach Boys, Pet Sounds (1966)

Reading list

Apollonio, Umberto. 1973. Futurist Manifestos. London: Thames and Hudson.

Blades, James. 1970. Percussion Instruments and their History. London: Faber and Faber.

Bridgett, R. 2010. From the Shadows of Film Sound. Self-published.

Cage, J. 1988. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Collins, K. 2013. Playing With Sound. Cambridge: MIT Press

Cowell, H. New Musical Resources Cambridge University Press, 1996 or http://zztt.org/lmc2_files/Cowell_New_Musical_Resources.pdf

Frith, Simon and Howard Horne. 1987. Art Into Pop. Suffolk: Richard Clay Ltd.

Goldmark, D. 2005. Tunes for ‘Toons: Music and the Hollywood Cartoon. University of California press 2005

Kahn, D. 1999. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Voice, Sound and Aurality in the Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kastbauer, D. 2011. Audio Implementation Greats #10: Made for the Metronome. Designing Sound.

Murch, Walter 2005. Transom Review

Walker, John A. 1987. Cross-overs: Art into Pop, Pop into Art. London: Methuen

Another great article, I live in México and it is very difficult to get in touch with professional stories and advices like this. Thank you very much!