Guest Contribution by Todd Baker

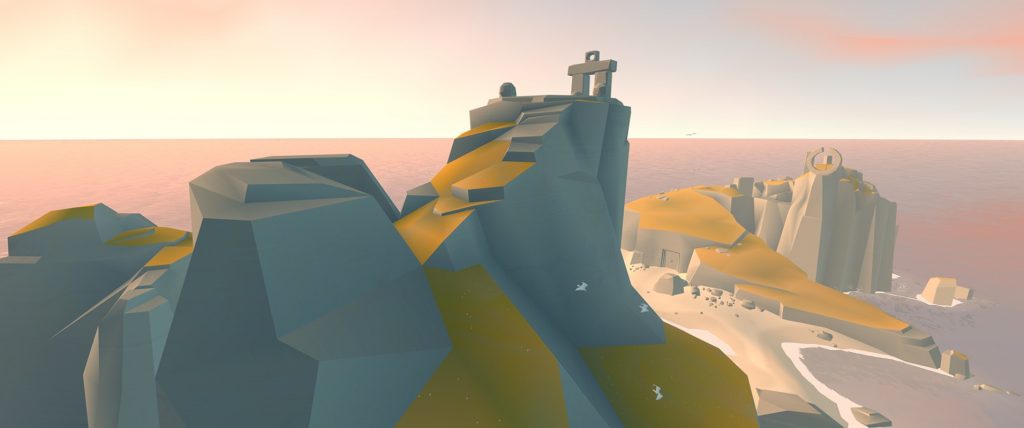

Land’s End has been described as ‘VR for everyone’. Ustwo began the project as an investigation into new methods of interaction and navigation in VR. Anyone who has tried the new medium will be familiar with the varied reactions from users; whilst many find the immersion compelling, others can suffer with disorientation, fatigue, even VR Sickness. Land’s End focuses on minimalist, intuitive interaction, set within environments that are immersive and welcoming – giving the player space to observe and breathe. Naturally the look, feel and sound of the world are essential in terms of creating a place that players can feel comfortable exploring.

Audio Identity

Even in early prototypes, the game had a distinctly dreamy, tranquil and surreal atmosphere. Many players have described the experience as ‘meditative’, and the audio definitely aims to support this feeling. Land’s End should feel like a world where players want to be.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/155730162[/vimeo]Footage of gameplay from opening level of Land’s End

Striking the right balance with ‘tranquil and meditative’ is a challenge, as there’s a fine line where things can start to sound like a 90s new-age relaxation tape. A lot of the sound design and ambient music could be described as ethereal drones and ambient textures, but I wanted the overall sound to have more of a stylised edge, and avoid the cliche.

Many sounds in the game were processed with tape-style saturation and flutter to varied degrees, and vinyl and other static noise elements are used heavily as a textural component in the music and interaction sounds. Uh-e Satin was a favourite (for the saturation effects, but also the tape-style delay / flanger) and the flutter component of Logic’s bundled Tape Delay is a great way of adding randomised analogue-style pitch flutter. Fabfilter’s Timeless and Saturn are also great for adding texture to overly pure or clean sounds.

There is an obvious tonal character to the overall soundscape of Land’s End, and it sits somewhere in between sound design and music, creating an intentionally blurred line between the two (more details on this later). The tonal sound sources were generally synth or guitar recordings that I heavily processed, often granulized and time stretched, but with a focus on creating more organic sounding results, as opposed to overly digital or glitchy artefacts. This was my first project following a switch to using Reaper as the main sound design DAW, and having enjoyed the non-destructive, quick time-stretching in Vegas for years, it’s great to see similar functionality taken to another level in Reaper. In terms of time-stretch algorithm options, region based pitch envelopes and the ability to go really extreme with the stretch amounts, Reaper has a lot of scope for creativity.

Challenges of audio for VR

It’s nice to hear many developers and players talking about the importance of audio in VR. I wouldn’t say it’s more important than it always has been (in established 3D game mediums) but it’s interesting that players definitely seem to be more directly aware of it, rather than it being a subconscious thing. In VR, people are more attuned to what sounds and feels right in an environment, and equally distracted by what doesn’t. Lands End is very much about immersion, creating a sense of place and transporting players to the world – so making the soundscape feel seamless with the environment is central to the experience.

The role of positional audio is bigger in VR. In any ‘traditional’ 3D game I’ve worked on, environmental soundscapes have been created using a combination of non-positional ‘2D’ layers (e.g. a stereo or surround layer of air/wind ambience) and positional ‘3D’ layers that have a specific position in the world (e.g. a crackling fire). Put simply, in VR the non-positional layers don’t really work as well. Hence almost all of the environmental sounds in Lands End are 3D. Even with no obvious object in the world to attach them to, sounds such as wind or distant ocean that make up the ambience are always positioned as a quad-array around the listener, so you feel a sense of direction:

As well as fixed positional sounds such as those on the shoreline, 4-point ‘quad’ sounds oriented around the VR camera-listener, in place of a base layer for ambient audio such as wind and air. This quad layer could dynamically crossfade as you move to the different ‘lookpoints’.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/155730158[/vimeo]Use of the quad ambience and spots demonstrated in-game (also in the other clips)

An obvious consideration with VR (but perhaps easy to overlook) is that people are only going to hear your mix on headphones. Wherever possible I worked on phones for sound creation, browsing recordings or synths, monitoring and mixing. I’m sure this influenced a lot of creative decisions – the usual differences with the perception of reverb, weight of transients, stereo imaging and ‘exposed’ high frequency detail meant that a lot of mix choices ended up sounding a bit strange, or at least very different on speakers – but I chose to stick with what felt best for the intended medium. Even when demoing ideas to the game team, making everybody listen separately on headphones was preferable!

To binaural or not to binaural

Unsurprisingly, HRTF filtering is often discussed in relation to VR audio, and there are some great solutions out there, some of which we tried – and the results can be really effective in certain contexts. Props to the guys at TwoBigEars, who were particularly helpful with their support for 3DCeption.

For a combination of technical, workflow and creative reasons, we ended up not using HRTF filtering in Land’s End. The creative side to this decision comes down to an interesting point about what represents a ‘realistic’ approach to sound positioning, and what we are used to hearing from more basic 3D positioning in games. For example, the HRTF approach reduces the hard stereo panning when an object is directly to your side (which I often interpreted as sounding less positional) and the filtering effects can change the clarity and character of sounds in a way that isn’t always desirable – especially with the effect on multiple sources in the mix.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/155805713[/vimeo]Back to back comparison of stereo and HRTF panning, using a waterfall spot over a 2D ambience.

Had the workflow been better (the combination of Unity 4, Fabric and 3Dception threw up some issues) I’m sure we would have used HRTF on selected sounds, but I still feel that the use of binaural filters is a creative choice rather than a direct advantage. Many factors specific to Land’s End made the effect less desirable: The minimalist and spacious environment design, the heavy use of water, wind and ‘noise based’ spots, the lack of cluttered positional sound sources (such as NPC’s talking or shooting at you) plus the workflow and performance considerations for a mobile VR project. No doubt binaural / 3D audio will play a big role in VR – perhaps exposing more fine-tune parameters of the HRTF filtering to the audio designer will help us to tweak the effect, to make it more tailored to the specific needs of a project, or even better, a specific sound.

A space for music in VR

There’s a tendency to be more aware of, and potentially more distracted by non-diegetic music in VR, even wondering “Where’s that coming from?”. We considered having no music at all, but it’s such an indispensable emotional tool, and Land’s End has a narrative arc that the audio clearly needed to support. There’s obviously a role for music in VR, but perhaps one that’s different to what we’re used to. The goal in LE was to encourage players to accept: this is how the world sounds. If they unduly notice something as specifically music or sound design, it’s likely that the all important feeling of immersion has been compromised.

With this in mind, one approach we took was to create a deep relationship between the music and sound design – intentionally blurring the line between the two. The entire game is actually tuned to a global musical key, so as you interact with the world, there are randomised tonal elements in the sound effects that harmonise with the subtle cues playing in the background. The obvious risk is that everything sounds samey, but even with a fixed key, there’s still scope for tonal variation through using the diatonic modes of the chosen key, which gives you a big emotional palette in terms of harmony.

A gentle approach to the use of music helped to keep it a subconscious part of the experience. The ambient music cues are always introduced subtly, and gradually build and subside in and out of the environmental ambience. We only introduced more intense, rhythmic music towards the end of the game. By this point players are more settled into the experience, and the subtle start gave us headroom to build the intensity for LE’s somewhat epic finale.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/155730161[/vimeo]A section of gameplay demonstrating the tonal relationship between the sound & music.

Understanding and crafting a final experience

The experimental nature of Land’s End meant that development was an iterative and explorative process. It wasn’t until the final stages of development that we could understand the nature of the overall experience, especially when it comes to things like pacing, or how it feels to move from one level / world to another. As with any game, there is a constant re-balancing of the audio as the design and art take shape. The more it feels complete, the more things are highlighted that need iterating or re-thinking. Early on in the project, when there were only a few mechanics in place (such as the system of basic movement between points) it was tempting to over-engineer audio for these mechanics, when it would later become obvious that a more minimal approach sounded better.

One system that had a last-minute overhaul was the wormhole-like portal transitions that take you from one world to the next. Rather than keep these as a generic sequence, we took the late decision to make each one sound unique, from the opening of the portal, to entering into the darkness, to emerging into the next world. We were able to introduce audible echoes of things you have seen, or from the world you are about to emerge in. It really helped with the overall feeling of progression and abstract narrative, and it’s nice to essentially turn ‘level loading’ into something meaningful.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/155730163[/vimeo]Portal transition. Level 1 – 2.

Land’s End was a small enough project to have just one audio artist behind all of the sound and music. My background has been very evenly split between audio design and composer work, so it was a great opportunity to take a more holistic approach, which suited the needs of the project and the challenges of the medium. While I love to work with bigger audio teams with multiple sound designers and composers, it was refreshing to have the control over how everything sounds – and made ideas such as tuning everything to a global key easy to implement. It was also a huge benefit to have almost full-time audio programmer support from Manesh Mistry at Ustwo – especially considering the relatively small team size. There’s definitely a completeness and personality to the audio, and it’s great to hear players picking up on this and responding well to it. Land’s End seems to have succeeded in setting some benchmarks for an immersive VR experience, and I look forward to seeing where other people take this exciting new medium.

===

Todd Baker is an audio designer and composer with many years of experience working on high profile projects in games and media. Aside from Ustwo, recent work includes projects with Media Molecule as an audio designer on the BAFTA-winning Tearaway games, as well as composing music for the LittleBigPlanet series. @TheToddBaker

Project: Land’s End

Developer: Ustwo Games

Platform: Samsung / Oculus GearVR (Android)

Engine / Editor: Unity

Audio middleware: Fabric by Tazman

Sound design DAW: Cockos Reaper

Music DAW: Logic Pro / Reaper

Soundtrack link: https://soundcloud.com/ustwo-games/sets/lands-end-original-soundtrack

Thanks for sharing Todd!

Ambient sounds are not the easiest to pull off well with HRTFs as the sounds are treated as point sources. Most people we’ve worked with end up creating a blend between stereo and HRTF to get a good mix of diffuse sound (and spread) while also getting a bit of the point source positional effect. On the other hand, we’ve found that b-format ambience works very very well in-game.

It is a shame that Unity’s memory leak for audio plugins could not be fixed in time!

Thanks Varun! Yeah, agreed re: the blend between stereo and HRTF. That’s definitely the way we would have gone had the memory leak / switch to Unity5 been sorted. For example, just adding the HRTF to one of the sources in the a quad array worked great. LE also had hardly any positional one-shot sounds, which is where I would imagine the filter working well.

Would be interested to know what you think about the idea of being able to tweak or scale the effect to be more subtle – or even offer an alternative hybrid / more subtle mode (per source) that could work better with static / multiple point sources.

Fantastic article! I really enjoyed attention and immersion of the sound in Land’s End. As someone who’s aspiring to become a sound designer in VR, do you have any recommendations for how to learn the ropes and eventually get hired?