This is a guest article written by Will Tonna, a sound designer and audio engineer based in the UK. He is currently the sound designer for One Minute, a play by Simon Stephens, which runs from September 10th to October 3rd at The Vaults in London. You can view his showreel and portfolio on his website LampEight Audio. This is a hold-over from last month’s “Favorites” theme.

On this month’s topic of “favourites”, I decided to share my thoughts on a somewhat underrepresented area of sound design; live performance and theatre. It’s an area that I’ve always felt most comfortable producing in and where my working practices have always seemed to best fit. Hopefully, through sharing my reasoning and experiences in sound design for the live experience, I can offer a glimpse into a lesser-known and exciting area for creative sound.

The funny thing is that theatre isn’t exactly in my blood. Short of a GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) in drama and a few weeks in stage school as a kid, live performance was never something I went out of my way to get involved with or felt any great pull towards. But when I took up an offer to provide sound for a performance art student during my time at college, what I found it offered me – and anyone else I would encourage to get into this exciting area of work – is an expressive and evolving environment for sound design, ripe for experimentation and interaction.

I’d like to share with you some of the key characteristics that drew me in to live performance.

It’s immersive

Because your time is spent creating and producing new sounds as opposed to cleaning and tidying up production audio, you’ll have the resources and space to focus your efforts on introducing immersive audio to the performance from the ground up. Sound is a powerful (and arguably underused) tool in any director’s arsenal.

With that being the case, there are 4 integral areas that sound can be used to enhance and highlight key visual areas in the live arena:

- Creating atmosphere – Either in a literal, scene-setting capacity (Where are we? What time period is it?) or creating an overall mood for what we are seeing (How are we meant to feel?).

- Highlighting key points – Employing specific events and triggers to nail key points in a performance (such as events, emotions, shock value, juxtaposition / anempathetic sound).

- As a narrative device – Considering voice-overs, internal monologues, ethereal and supernatural constructs as well as flashbacks and memories to add additional depth to the plot.

- Accentuating dynamics – Making your sound design responsive to what’s on stage. However, because of the non-linear nature of live, the dynamics of a performance may not be necessarily pre-defined so the sound may need to be decided or even generated on-the-fly.

Although these areas all correlate with traditional and linear media, live performance inevitably gives you more room to be creative with the physical space you’re working in and with the visceral and shared experience that is intrinsically linked to live as a medium. Just like with good film sound, you need to be able to transport your audience out of the space they are in and into the space you want them to feel as if they are in.

Sound can be prompted by some form of audience interaction or—in the case of an art installation—in relation to where they are positioned within the space. Anything can be used as an input to affect the sound dynamics, physical or otherwise. Nothing demonstrates the enveloping nature of audio for live performance more than the current Soundscapes exhibit at The National Gallery, whereby sound artists and musicians have been specially commissioned to provide an audio backdrop to some of The National Gallery’s most iconic pieces of artwork. I went along recently and was blown away by how the sound created such a dynamic and animated experience, even alongside entirely static centrepieces.

It’s Non-linear

The scariest realisation when working in live is that you suddenly lose control of the linear nature of most traditional media. Now you’re working with timings as opposed to SMPTE. That means one stumbled line from your performers or a small delay in your lighting rig and you could send your entire soundscape out of alignment with the visuals. I’ll often work to scratch video recordings of specific scenes or performances that need tight choreography and timing. If I can get to the rehearsal space in person, that’s even better. But as with an “unlocked” piece of film, the timings, movements and actions are destined to change almost on an hourly basis, and keeping up with the edits can be tricky.

Doesn’t sound like much fun so far, right? Though this is where your ingenuity as a professional sound designer comes in. You need to account for any potential pitfalls on the night and make sure your work is entirely fail-safe. Fortunately, there’s a number of techniques you can use to counteract this.

One example of this is by padding out the length of ambiences or transitional sounds to extend far beyond the estimated length of the scene. This way, if the scene ends up over-running for whatever reason, the operator will have the ability to delay triggering the next sound until the performance has caught up without running the risk of a total sound cutout.

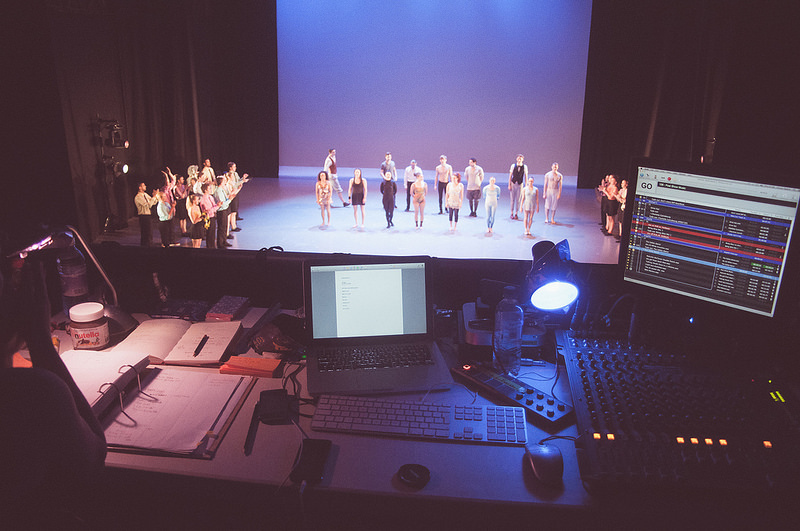

This technique relies on each element of the sound design being made independent of one another and that your QLab project (or control desk software equivalent) is set up correctly. Because you’re building the soundscape on a layer-by-layer basis and keeping each of the individual assets separate from one another (as opposed to creating a cohesive render of the entire project), you have a very high-level of control, even at the playback stage. In fact, at this level, many parallels can be drawn between live performance sound and the basic framework for another key non-linear format: game audio.

You’re forced to be flexible

One of the key considerations with any live project is the venue itself. Although any sound technician worth his salt will be able to tailor the sound to work with the performance space from an EQ and levelling perspective, you simply don’t have the luxury to print sound-to-picture and relax knowing the playback venue has the acoustics taken care of at their end.

One of my clientele is a close-knit group of friends who were brought together through their interest of combining sound, visuals and other multimedia elements into traditional fringe theatre. A couple of years ago, we travelled up to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival with our latest show. The problem we faced was that the space we were performing in was an unknown variable. We didn’t know how the sound would translate: what the acoustics were like, whether the sheer scale of the room would drown out the designed ambiences, how much bleed were we going to hear from the nearby road… The list went on. This wasn’t going to be the case of pulling some last-minute EQ edits. We needed to fundamentally go back to the source files and make tweaks to reverb levels and other intrinsic properties.

So, a far cry from being the guy who delivers the assets and calls it a day, I needed to be up there with the cast and crew making sure that the directors weren’t going to be fighting against the venue by employing a little bit of live sound engineering know-how to get the sound to work in this new context. We pulled late nights and early mornings making minor level tweaks, dropping stuff that didn’t work and creating fresh content to fill those gaps.

It was one of the most exhilarating experiences of my life. When you’re in close proximity to a group of like-minded people at the top of their game in what they do—sharing a combined vision of the lasting effect you want the performance to create—you all reach a sort of mutual flow in what you do, and the quality and quantity of your work increases exponentially. It’s an amazing feeling and one I’ve only achieved by being locked in a very big room with a bunch of actors (as strange as that might sound). It’s why live sound is my “favourite” type of sound design work.