Working in post sound, there tends to be a lot of commonalities between projects. In general, we don’t start work until the picture has been shot and edited. When the files come in, we divide up the editing, record foley, record adr, and schedule the final mix.

The post sound process for an animated film is a little different. Most notably, work begins before a single frame of picture is drawn. To better understand how sound is made for an animated film, I will be walking through the post-sound process for an animated short I designed and mixed, Tightly Wound.

Tightly Wound started as an essay, written by Shelby Hadden about her personal experience with pelvic pain. Shelby then partnered with fellow filmmaker Sebastian Bisbal and they developed the essay into a script. I had worked with both Shelby and Sebastian on past projects, but for the three of us, Tightly Wound was our first large-scale animated project. Sebastian drew all of the frames in Photoshop using the AnimDessin plug-in and did all the final compositing in After Effects. By the end of the process, Sebastian ended up hand-drawing over 8,000 frames.

In March of 2016, Shelby sent me a script and I worked up a budget for doing sound on the project. While I knew the process would be different than a typical narrative project, I was able to look at the script and fairly accurately determine how much time I would need to give the film the attention to detail it would require. By the end of the process I am proud to say we ended up sticking to our initial budget!

Work for me on the film began in late August of 2016 when we recorded voiceover for the teaser trailer. From here, Sebastian and Shelby made selects and assembled their favorite takes in the timeline in After Effects; they then animated around the voiceover we had recorded. By early October, Sebastian had enough of the animation done that we scheduled our first foley session with foley artist Susan Fitz-Simon over at Soundcrafter.

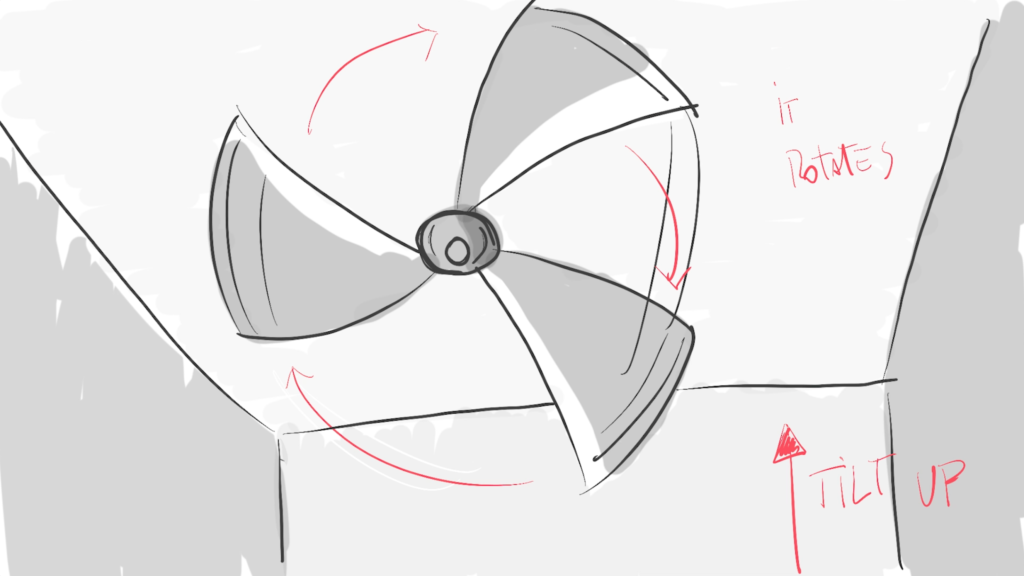

For me, bringing Susan on board was key for this project. Susan had become my go-to foley artist at this point. By then, we had worked on a few projects together and had built a great relationship. With Tightly Wound, a lot of the sounds we needed were more design-heavy than just your typical project, so I really leaned on Susan’s ability to look at an action, talk through how we wanted it to sound, and pull something out of her prop closet and have it make the sound we needed for that moment. While we were doing the foley session, many of the shots were still in animatics, so we had to improvise to fill in the blanks with what we thought it should sound like. Part of this meant coming up with an idea, Susan coming up with a few options, and us rolling wild on multiple variations for us to then plug into the final film.

Probably one of the more challenging sounds we needed to create–where this approach worked really well–was with the stretching sounds in the film. We wanted to be able to communicate the discomfort Shelby was feeling, while keeping it from sounding too squishy or gross.

During this and subsequent foley sessions, we experimented with a lot of different materials to strike the right balance. We ended up using a combination of different materials from shot to shot. I know we recorded several gloves–kitchen and surgical–as well as some balloons, leather, and a bit of wet chamois for a little bit of squish.

With these as building blocks, we would then layer in different combinations, sometimes pitch-shifting the elements or slowing them down. We would then export different variations and get feedback from the filmmakers.

In the trailer there’s a moment with a train; this we ended up pulling elements from the Boom Trains and Pro Sound Effects Odyssey Collection. For the actual crash, we chose to do some metal impact sounds as foley. Other elements like backgrounds and some of the walla (background chatter) were also cut from libraries. In general, we tried to use as many original sounds as possible.

By the beginning of November, the animation for the teaser trailer was done and we scheduled a mix. You can watch the trailer here:

From there, Shelby went into fundraising mode: she launched a Kickstarter campaign and was able to raise just over $30,000 of her initial goal of $20,000!

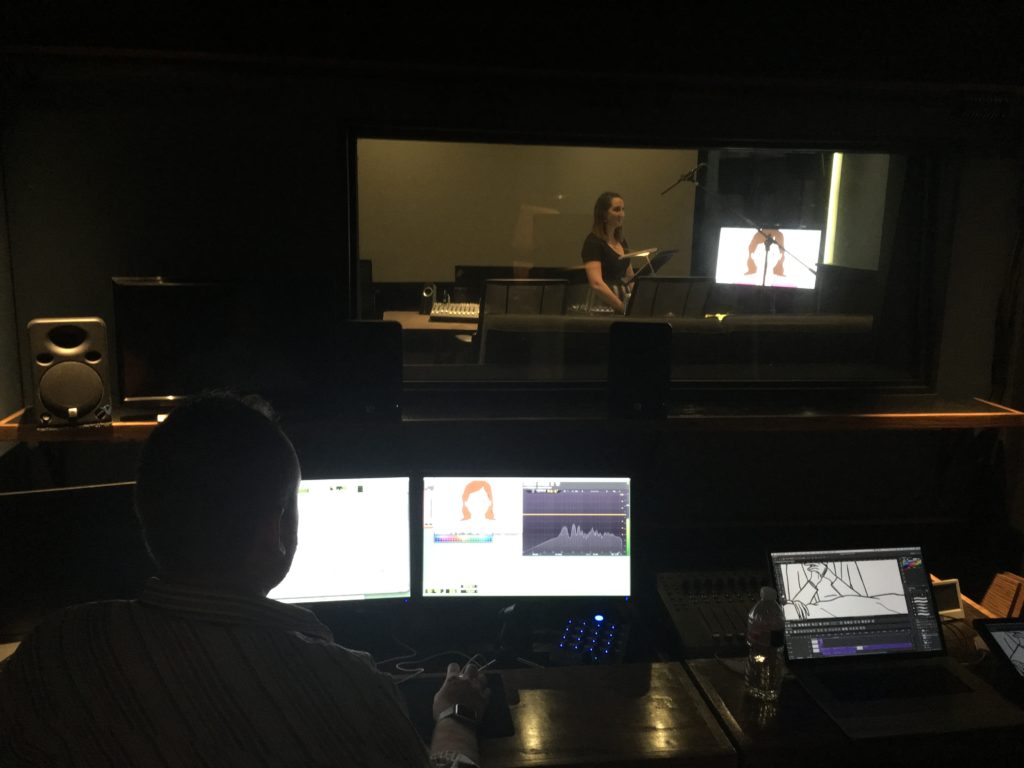

Once funding was secured for the project, Sebastian and Shelby started in on the animation. In March of 2017, we started with a collaborative google sheet and began the process of potting design elements we knew needed to be created. In April, we recorded all of the lines for Shelby as well as “the jerk” and her therapist over at Chez Boom Audio here in Austin. I love the vibe over there–especially when you have a short period of time to record a lot of lines, having a comfortable space for your actors can really help a session go well.

In May of 2017, Shelby and Sebastian had finished work on Scenes 1-4 which were around 90 seconds total. We scheduled another foley session to fill in the missing sounds and did another mix for this portion of the film. Luckily we were able to use a lot of the design elements we recorded in our first session to fill out a lot of the recurring sounds. This version was then used for promotional and fundraising purposes as they continued to animate the rest of the film.

From there, sound took a back seat for a few months until September 2017. By this point, timing for the scene had been relatively locked. Scenes 1-4 were done and the rest of the film had at least animatics from us to work off of, so we were able to schedule our “big” foley recording session and spend a day and a half on the foley stage with Susan really filling out the design for the whole film. For any animation that was done, we would record the foley to sync. Then with any scenes that were still rough on timing or in animatics, we would watch what we had and roll wild on a few variations for me to have more options when cutting to the final picture later on. I think Sebastian was a huge asset for this part of the process; while cueing the foley session, I could send him a text and find out how close timing was for anything that was still rough and he could give me a better idea of what the final product was going to look like. Sebastian was also able to sit in on part of this session, so was great to be be able to get feedback in real time.

This behind the scenes video shows a part of our foley session at Soundcrafter:

Once we finished the foley session, I did a temp mix with the new design elements cut in so Shelby could start submitting the film to festivals while they were finishing the animation.

In October 2017 we booked another VO session–this time back at the newly opened Soundcrafter–for young Shelby, some of the background characters, as well as re-recording some of Shelby’s lines that had either been re-written or needed to be re-recorded for performance. In November we did another temp mix with the new VO cut in and some of the sound design more dialed in as more of the animation was completed.

From there, sound took a back seat again until January 2018. At this point, we could start adding music from composer John Churchill. The trailer had music, but until then, the various temp mixes we had done were without music. Adding music lead to some re-balancing of some of the design, but luckily Shelby had a great sense for sound and was really great about knowing where she wanted either the music or design to take the lead. We again re-recorded some lines for performance, and started in on the final design and mixing process. This involved some back-and-forth between Shelby, Sebastian, and myself; frame.io ended up being one way we did this. It’s great because I could upload a new QT with the latest mix and get accurate notes with timecode for things we needed to tweak.

By March 2018 we were ready for the final mix. The total run time for the film was just over 10 minutes, and most of the design and editing work I was able to do at home. For the final print mastering, Shelby and I met over at Soundcrafter. While I trust my room at home and know it translates to a big room, it is always nice to hear it in a larger room on a big screen. Luckily by then we had gone back and forth enough that the only tweaks we were making were balancing the music and design versus the dialogue in a few of the bigger moments, which was great!

From there, we were done: as the primary target was festivals, we focused on getting a solid theatrical mix in both stereo and 5.1. I also used Nugen’s LM-Correct to generate both broadcast and web mixes for the film. Since its release, Tightly Wound has screened at a number of film festivals around the world, including Annecy International Animated Film Festival in France, Anima Mundi in Brazil and the Austin Film Festival. Tightly Wound is now available to view online for free via Condé Nast’s Iris Platform:

By the end of the process, we had a film that looked and sounded great. I feel very fortunate to have been part of this project. While I have worked on a lot of films with some great opportunities for sound, post-production on a short film is usually very quick. With Tightly Wound, I was able to get involved early and be a part of every step in the filmmaking process.

When creating the sound for an animated film, by far the most important aspect is to have an open line of communication with the filmmakers. Unlike any other type of film, you have the unique opportunity to create the sounds as the images are being created–this allows the individual elements to become a core part of the film.

Don’t wait until the end of the process to start designing sound.

My biggest takeaway from working on Tightly Wound is reinforcing the importance of getting involved on a project as early as possible. I could not have hoped for a better experience on a project. Making post-sound part of the filmmaking process from script to screen should not be limited to the world of animation. Even on live-action projects, I try to get involved during pre-production. If I have a relationship with the filmmaker, I’ll ask to read the script before they shoot. This gives us a chance to start thinking about sound and are then able to talk through potential challenges they might encounter while shooting and come up with a game plan on how to deal with those challenges. This can be by getting extra coverage or capturing wild lines on set. In some cases I may even visit the set to capture key non-dialogue sound elements that are unique to a location.

We are all creatures of habit, but sometimes changing the way you work and thinking outside the box can lead to creative decisions you would not arrive at otherwise. Talking about sound early and often can only lead to a better end result. While every project is different, I hope this insight has been helpful and enlightening for anyone interested in creating sound for animation.

Korey Pereira is a freelance sound editor and mixer based in Austin, Texas. He is an active member of the Motion Picture Sound Editors (M.P.S.E.) and a Lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin.