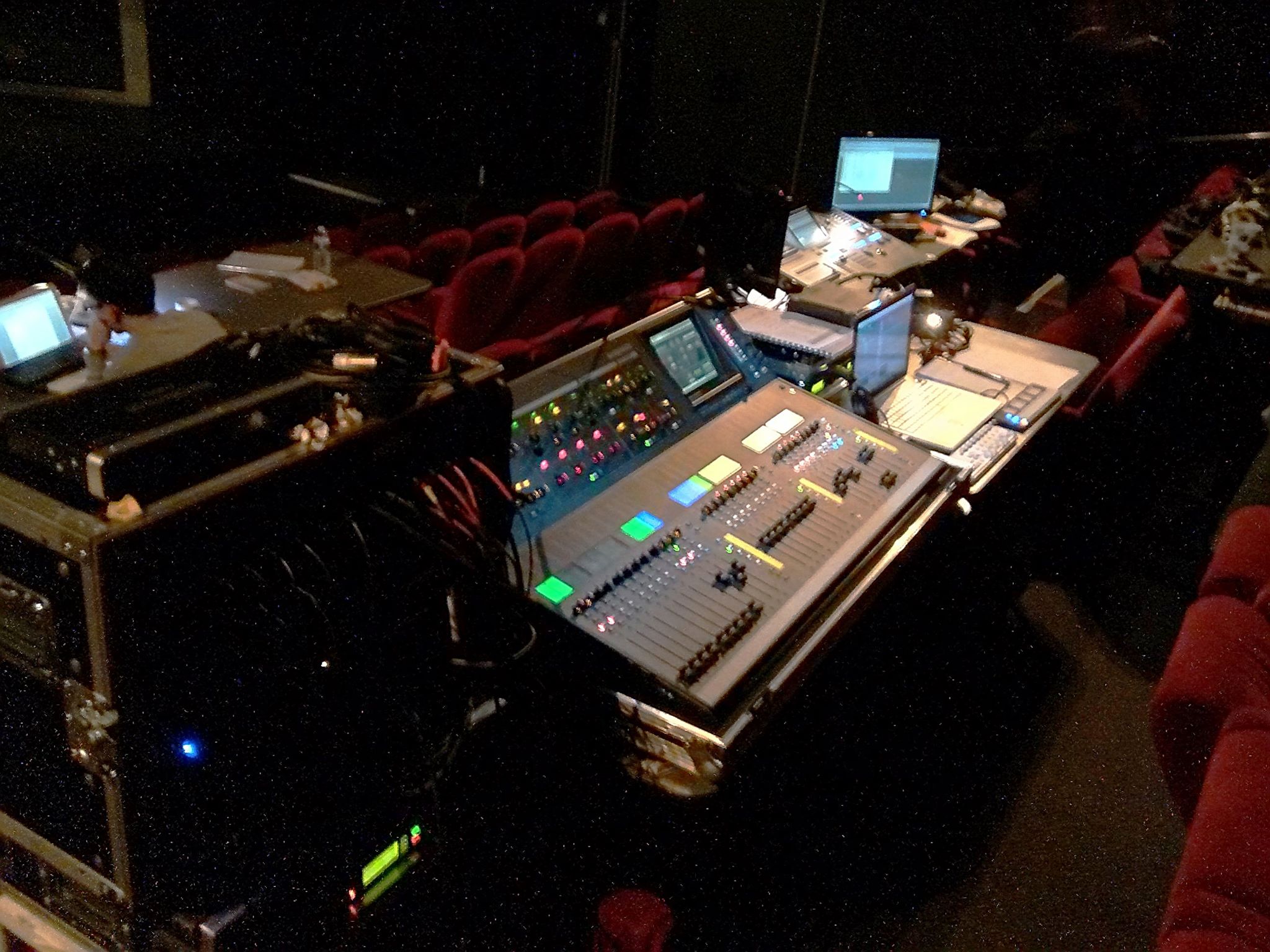

Baptiste Chatel’s workstation in Rennes (France)

This article is a guest post by Baptiste Chatel (Dijon, France) who “works virtually everywhere in Europe as musician and sound engineer” and “likes low sounds, high sounds, and every other type of sounds in the middle as long as they are loud”.

The Beginning

I started working in theater as an amateur actor when I was studying psychology, around 2005 in the University Theater in Dijon (France), where we worked on Faust by Christopher Marlowe.

One day, during a rehearsal, a guy came over with his laptop, an audio interface, plugs it into the sound system and started playing some tunes for the play (some made by him, some ambiances and some famous ones). I used to play music up until I graduated from high school and, this day, really felt like going back to it. It was also my first encounter with what seemed to be a weird piece of software which piqued my curiosity: Ableton Live 4.

During the next year, I became the “sound & music guy” of our small company. I started writing some music for the theater with Live and was back to playing guitar & computer with a band during a movie projection of Vampyr by Carl Theodor Dreyer. I didn’t know anything about sound design for theater at that time, and only thought of myself as a musician for the company, writing a set piece of music, playing it in stereo… nothing outstanding. I had zero knowledge about sound systems and barely knew how a mixing console worked.

A few more years laters, I decided to end my studies before graduating. I was actually spending more time making music, working for my small theater company and rehearsing with my band than studying. I started to look into consoles, mics and all the possibilities offered by a show venue. I was pulling off cables, plugging mics, setting up drumkits, theater curtains and speakers, and was even earning a bit of money for that! When a theater company seemed to have a sound(wo)man or a musician (and not just playing a CD), I always tried to have a look and understand their work, where they were placing their speakers, their mics, what kind of effect they got, what type of gear they were using…

Baptiste Chatel

What really impressed me the most, I think, is the depth obtained by placing speakers far away. It might seem like a silly thing to say but it’s something we cannot hear in a movie theater. Typically, when going to the movies, we only have a 5.1 system with 3 channels aligned on the screen. No sound come from further away than the screen, and we can definitely feel that. In the theater, the whole volume of the scene can be filled with sound. The scene and the whole venue have sonic properties and we can use them. That feeling of depth really pushed me and motivated me to develop my craft as a sound designer.

I give a lot of value to the furthest sounds (from the stage background); those are the ones surrounding the actors, it’s the sound of their world. To fill the stage, I often use a sound system at least as powerful as the main system. My speakers can be fixed at the top with the spotlights (pending the lighting designer agreement), on a stand in the stage background or on the floor, which helps reducing their visibility. My favorite technique regarding playing ambiances is still the direct them to the back of the stage and therefore improve the diffusion and refraction. It’s a great way to blur the localization of the source.

When working for the theater, using several planes seems mandatory to me. I always use at least one sound plane close to the scene and another one further away from the stage. Along with that, I often add a couple of speakers on every side of the audience, as if they were wearing a massive pair of headphones, in order to widen the sonic scene and amplify the stereo effect. Depending on the venue, another plane from the back of the audience directed towards the stage allows me to give a proper surround impression to the audience, but I was rarely able to expand the sonic scene to this point -unless of course the actors played there!-.

Finally, a central channel on the ceiling allows me to give a specific status to some of my sounds, like a phone call, or to localize some of them (like having some rain playing on a roof). Since the majority of my sounds goes from a plane to another or are played on several planes at the same time, I set them up with a calculated latency depending on their distance to the furthest broadcast point.

Picture by Donald Tong

Being there from the beginning

During the years, I learnt that being there as early as possible during the creation of a play allowed me to do a better job. It allows all the people involved to develop a shared aesthetic, and allows me to add my own references to the project and include my own universe to the ones from everyone else. Very often, someone would give me some musical references during the first work sessions. If I’m added to the project after some reading sessions already happened, the actors or the director often bring some tunes or albums with them. It’s very important to get some inspiration from those or at least understand why a specific piece of music would fit here. It can then become an interesting starting point, and discussing their musical choices even allows them to understand what a sound designer can actually bring to their play.

Furthermore, by keeping a closer relationship, it’s then easier to foreseen the more technical needs that might arise. If building a set is on the table, it’s always better to know that, notably if it needs sound. Likewise, avoiding small or resonating places is always appreciated! Will the actors be equipped with a mic? In which scenes? Is it really mandatory?

Being flexible

While creating, I’m trying to be as reactive as possible. My workflow is quite simple and based on Ableton Live (with a touch of Max for Live and Pure Data). I couldn’t work without it.

Most of the time, I work on the main set of the show, where I create my ambiances and design them live. When I have a bit of free time, during the actors’ break or while some more technical work is in process, I clean and sort the various sounds by their play order and by usage.

The upper left part of my set is made of elements that will almost definitely be part of the show and are sorted. The bottom right part contains everything else. As time goes by, I polish and gather. Some parts of the show are made in other sets if they are too complex, then imported in the main set.

The main idea behind this process is being able to go back to any aspect of the soundscape and allows the whole team to quickly and easily test various possibilities. Once the idea is approved, I find the right fade-in/fade-out time along with some other variations. I use the dummy clips mainly to have a long fade-in on a looped sample. The Follow Actions are also extremely convenient to make random variations on ambiances. In order for my set to stay readable, I name my scenes and group my ambiances in track groups. Usually, when I’m done creating my soundscape, browsing my set requires as less horizontal scroll as possible in order for me to be able to locate things as quickly as possible. To play the piece, I use one or several control surfaces -a Nanokontrol, a Nanopad, a BCR2000 with a couple of footswitches, a QuNexus, …-, which allows me to play and manipulate my sounds live. I like to keep a part of acting and manipulation during the representations in order to be able to follow, guide and play along and with the actors.

Baptiste Chatel’s main gear

Every sound has a source

Which sounds are coming from the sound system? Which ones are from the stage? I like to use sounds from the stage when possible rather than just playing an effect. If a cellphone has to ring, I suggest that it should actually ring; another actor backstage can call an actor on stage. If a radio has to be used, let’s use a real one! If it has to play a specific music and be moved around, let’s disguise a mp3 or tape player as one! During a show filled with sounds, a real sound coming from the stage is quite refreshing and the actors usually like having accessories. It gives them another way of having some weight on the show.

I barely scratched the surface of this topic. Every piece is different, and so is every venue. Sound for theatre requires a lot of experimentation, which is quite similar to working in a recording studio. On another side, the expected result is quite close to the one expected in movies. Sound design for the theater also requires to work live and closely with the actors, a bit like working for a video game. It’s an activity that requires you to communicate, to plan, to have a good knowledge of the gear and pieces of hardware used and, most importantly, to be extremely curious.