Last year I wrote a piece for DesigningSound caled “Failure in the Pursuit of Perfection” in which I shared how perfectionism sometimes led me to total and utter failure. I thought it might be interesting in this month of “Failure” to take a look at how the reverse can also be true.

Of course there are some mistakes that are just that, errors, flubs, muddles, gaffes, miscalculations. Sometimes they’re inexcusable…

There are however plenty of examples where artists have essentially failed, made mistakes and imperfections in their work (sometimes intentionally) that went on to define them and push the boundaries of the language of art further outwards. Here are just a few…

Intentional Mistakes

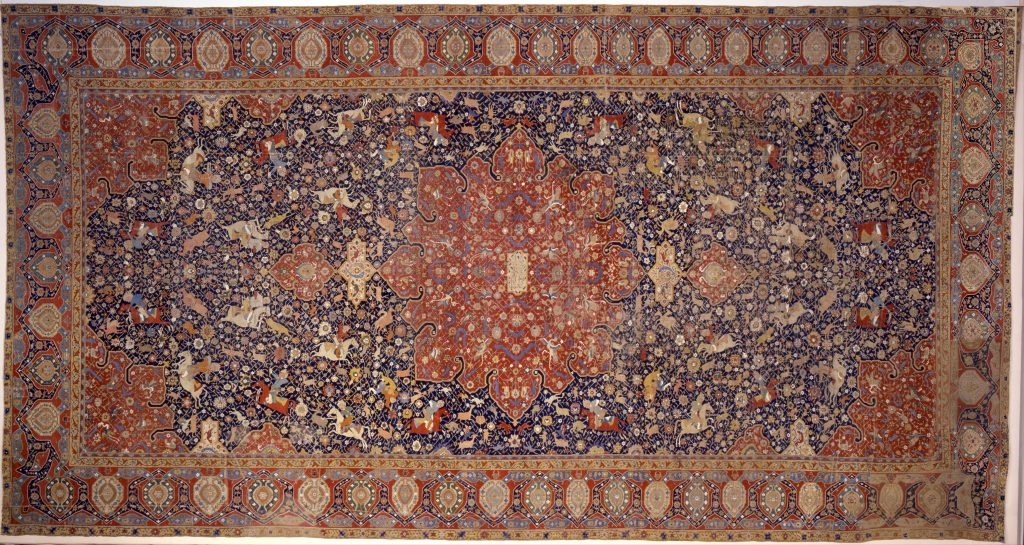

It’s pretty well known at this point that fine Persian rugs almost always contain intentional mistakes. There’s a Persian proverb that says, “A Persian Rug is Perfectly Imperfect, and Precisely Imprecise”. The practice stems from the religious belief that God is the only perfect being, so attempting to create perfection is like claiming you’re God.

Go on, try and find the error in this one… I’m pretty sure Waldo’s in there somewhere.

Sometimes a mistake isn’t merely just present in a piece of work, but it actually defines it. Julia Margaret Cameron was a victorian era photographer who’s work was criticized for mistakes she made intentionally. She would put her subject a little out of focus and use the development process to purposefully create flaws though uneven use of chemicals. She pushed the boundaries of photography which was still a relatively new process that was predominantly concerned with faithful reproductions of subjects. Julia Margaret Cameron saw potential in it where others didn’t and moved it from a technical skill, into an art form, all though making “mistakes”.

Unintentional Mistakes

I’m fascinated by the language of film and how it developed. Today we take so much in the medium for granted. Filmmakers can cut from one location to another, one moment in time to another, have a character’s inner thoughts voiced without their mouth moving on screen, play sequences in slow-motion reversed or develop a whole narrative backwards (check out Gaspar Noé’s disturbing “Irreversible”), all without phasing the audience at all.

This was not always the case however. There was a time when a less film-literate audience supposedly ran for the doors at a screening of the Lumière brothers’ “L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat” (The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station) as they believed the train was about to burst forth from the screen (or so the story goes). This was at a time when the language of film was still in its infancy, when many of the techniques that we take for granted today had yet to be discovered and developed.

One of my favorite stories about the development of the language of film concerns the practical effects pioneer, Georges Méliès. The story goes that he was filming a street when all of a sudden, his camera jammed. Without moving the camera, he tried to fix it and after a little time had passed, he resumed filming. Upon watching the film, Méliès was stunned when he saw a horse and carriage suddenly and seemingly magically turn into a hearse. With that, the “Jump-Cut” technique was born.

Here’s an example of Méliès using this practical effects technique.

Last week I was watching “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years” on Hulu. About halfway though, Ringo told the interviewer how the infamous reverse guitar part for “Tomorrow Never Knows” came about. Apparently John Lennon (who Ringo describes in the documentary as “not mechanically minded”) mistakingly took a tape recording of a guitar to the tape machine, put it on believing it would play from the start, but instead it played from the end in reverse. They went on to use the reverse technique in numerous songs on their records.

You can learn more about John Lennon’s strange production suggestions and requests that influenced the sound of the band in this Vulture.com article.

Lastly, just last week I was writing a piece of orchestral music that called for some taiko drums. I loaded up some instruments in MOTU’s Ethno and perhaps after writing a piccolo melody (or something else high in range), returned to the Ethno MIDI track with my keyboard shifted up multiple octaves. When I went to play the drums, I instead heard a glitchy electronic loop. It may not have been right for the piece I was writing at the time, but next time I need a glitchy loop, I intent to recreate this mistake!

So push your tools and test your instruments. Try to make a mistake, or better yet, try not to. You’ll surely fail and the result may be just the thing you needed.

Great article! Finding inspiration in things that are supposed to be “just” errors is always great! I recently noticed some weird glitchy sounds that only happened upon switching between presets in a delay plugin & went on to record them. It’s become another technique for creating interesting source sounds for further experimentation.