Guest Contribution by Keith Lay

A special thank you to Keith Lay for this contribution which explores acoustics from the unique perspective of a musical composition and performance. Keith is a composer, producer, and educator based in Central Florida.

On October 20, 2012, musicians placed on rooftops, steeples, and lake boats in downtown Orlando, Florida performed “inSPIRE for 22 Brass, Carillons, C Bell and Distance” – the first experiment in “Distance Music”. The Orange County Arts & Cultural Affairs department supported the project as a part of National Arts and Humanities month.

Distance Music Concepts

As sound travels to a specific location, it is delayed by the distance in which it must travel to reach the target location or specific site. Distance Music accounts for these delays by having musicians farther from the audience play earlier, so as to make up for the time required for the sound to travel the distance.

A Distance Music piece is intended to be performed at a particular location, such that a listener cannot hear it correctly at any other place unless the distance, altitude, and terrain between the listener and music groups at that place are the same as those at the original environment. For example, inSPIRE cannot be performed in any other city than Orlando, or from any other rooftops, steeples, etc., than those for which I wrote it. Furthermore, the audience can only perceive the composer’s intentions in balance and counterpoint from a premeditated site (what is referred to as the “sweet spot” in this article).

Large-scale auditory events fascinate us: the clap and roll of thunder, mountain echoes, waterfalls, long trains, ocean surf, a pack of coyotes howling in the distance. Distance music sounds large, if not loud, because it surrounds the listener with sounds from afar. Due to a location’s unique assortment of shapes, structures, and materials, among other characteristics, sound reflects with a plethora of tints and tones, which distinguishes outdoor music from its indoor equivalent.

Sound anomalies in pitch and dynamics are expected from stations at higher altitudes and farther distances due to the changes in temperature and wind. Sound travels at slower speeds in cooler temperatures. When sound passes through an area of different temperature called a “thermal layer”, the direction of the sound wave will bend much like how light bends when passing through a lens; cooler thermal layers are common several hundred feet above the ground, warmer thermals exist on the ground from the sun. As well, the wind condition also affects the sound to produce unexpected results in amplitude.

Historical Precedents

Being naturally visual creatures, we like to place whatever items we focus on in front of us. Our ears are particularly sensitive to sounds emanating from what we face. Antiphony (“opposite voice”) challenges the in-front soundstage norm by placing groups of instruments in opposite directions. The classical canon includes many examples of antiphony. Giovanni Gabrielli composed brass and choral music in the 16th Century that simultaneously utilized musicians placed at opposite naves of the San Marco cathedral. Centuries later, Berlioz and Mahler wrote parts for hidden, off-stage ensembles to create an illusion of memory or fate. Antiphonal works by composers of the 20th Century (most notably Charles Ives and and Iannis Xenakis) further explored the use of direction and space. More recently, Kalevi Aho’s Symphony No. 12 was composed as “Spatial Music,” which surrounded the audience with musicians for a performance in a ‘natural surround’ location: the slopes of the Finland’s Luosto Mountains. These antiphonal and spatial approaches to composition provide a wider palette of elements with which composers could develop a musical concept, while enhancing the visceral and experiential quality of listening.

Inception of inSPIRE

Terry Olson, the Director of Orange County Arts & Cultural Affairs, asked me in the Summer of 2012 if I was interested in writing a work for the Creative City project, one which would use the carillons of the downtown churches. After listening to one of the carillons, we decided that the proposed project would be too quiet to be heard over traffic. I suggested adding trumpet players to the roofs and steeples. But why not take it further? How about brass players playing from city building rooftops at the same time? It was at that moment that I realized the composition could be written to take the speed of sound into consideration by back-timing the entrances to create a precise musical experience. Terry began seeking permissions to place musicians on rooftops in downtown Orlando for an October 20th concert. From an initial mapping of possible locations, we chose the Disney Bandshell location in Lake Eola Park because of its proximity to the most interested parties. The Lake Eola area also contained several churches, a mixture of building heights, available parking space, and rented pedal boats. Terry began focusing his efforts to find more locations in that area, while I began looking for musicians who would contribute to our event.

Synchronization Requirements

Precise timing from every station was crucial to the success of the concept. Since the large distances between stations made a traditional visual conductor impractical, I asked my twin brother Kevin to create an iOS application for the project to provide synchronization by employing the built-in world time clock. Each device could function independently because live data was not required once the app was loaded. It featured an adjustable start time and a 120 bpm tempo visual with audible click. It also displayed the count-in to the next rehearsal letter on the music. Unfortunately, too many challenges stood in our way of using the app in time for the performance, from musicians potentially lacking an iOS device to not having the time to fully troubleshoot the app in order for it to function properly (as well as to get it approved for downloading from the Apple App Store). The iPhone conductor app concept was scrapped in favor of something slightly simpler, and very reliable: renting 13 Motorola CP500 UHF two-way radios. Every station received a radio, which was capable of transmitting within a 2-mile radius. Through these two-way radios, I broadcasted general voice messages and synchronized timing with a live metronome click from my iPhone. To keep the unfamiliar music together, I called out an 8 beat countdown to each rehearsal letter during the performance, which were placed frequently through the score for this purpose. An extra musician, identified as the “conductor” was needed to hold the radio in a position that the musicians could hear it, and to start physically conducting if the musicians were unable to hear the metronome over their playing.

Calculating Time Delays

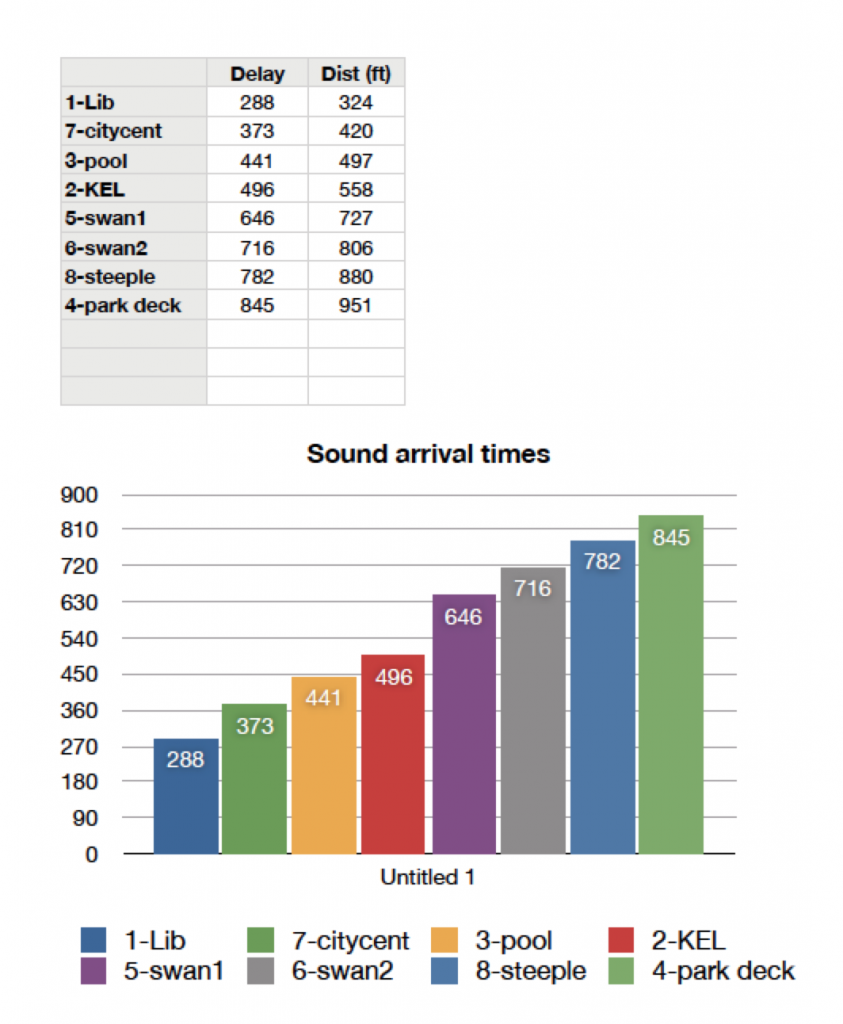

About a week before the premiere, the station positions for inSPIRE were finalized so I could finally begin composing the work. The “sweet spot” for the musical mix was moved to an open, paved area adjacent to the Disney Bandshell in Lake Eola park. At this stage, the distances from each station to the “sweet spot” were measured so that the time that sound would require to travel could be identified. Distances to each of the locations was determined with Orlando’s online platt map, and a speed of sound at 70˚F. 344 meters/second was chosen for calculations.

Calculating delay time for each station was a simple function of distance/344m per second, so if every musician played a note at the same time, the order of arrival would be from closer locations to farther ones, and knowing the sound travel times was integral in creating the appropriate mix at the “sweet spot”.

Swan Boats

Unlike every other instrument station in the work, boats could be placed at any position in the lake. The Lake Eola swan boats have a flat floor and had enough room to carry a musician, music stand, and second passenger. The second passengers served as “captains” of their pedal boats, keeping their onboard musicians at a predetermined distance from the sweet spot. These boats allowed me to fill in the sound arrival timing gap between the KEL Tower (496 ms) and the Baptist Church steeple (782 ms). Swan boat station 5, at 806ft from the “sweet spot”, was to stay close to the north shore; their point of reference was a tree in line with the east side of the easternmost office building. Swan boat station 6, at 727 ft., was to align with the middle of the third large building along the southern shore. The reflective nature of the water and the slightly cooler air over it would help project the sound to make these distant solo instruments audible in the “sweet spot”.

Music Notation of Arrival Times

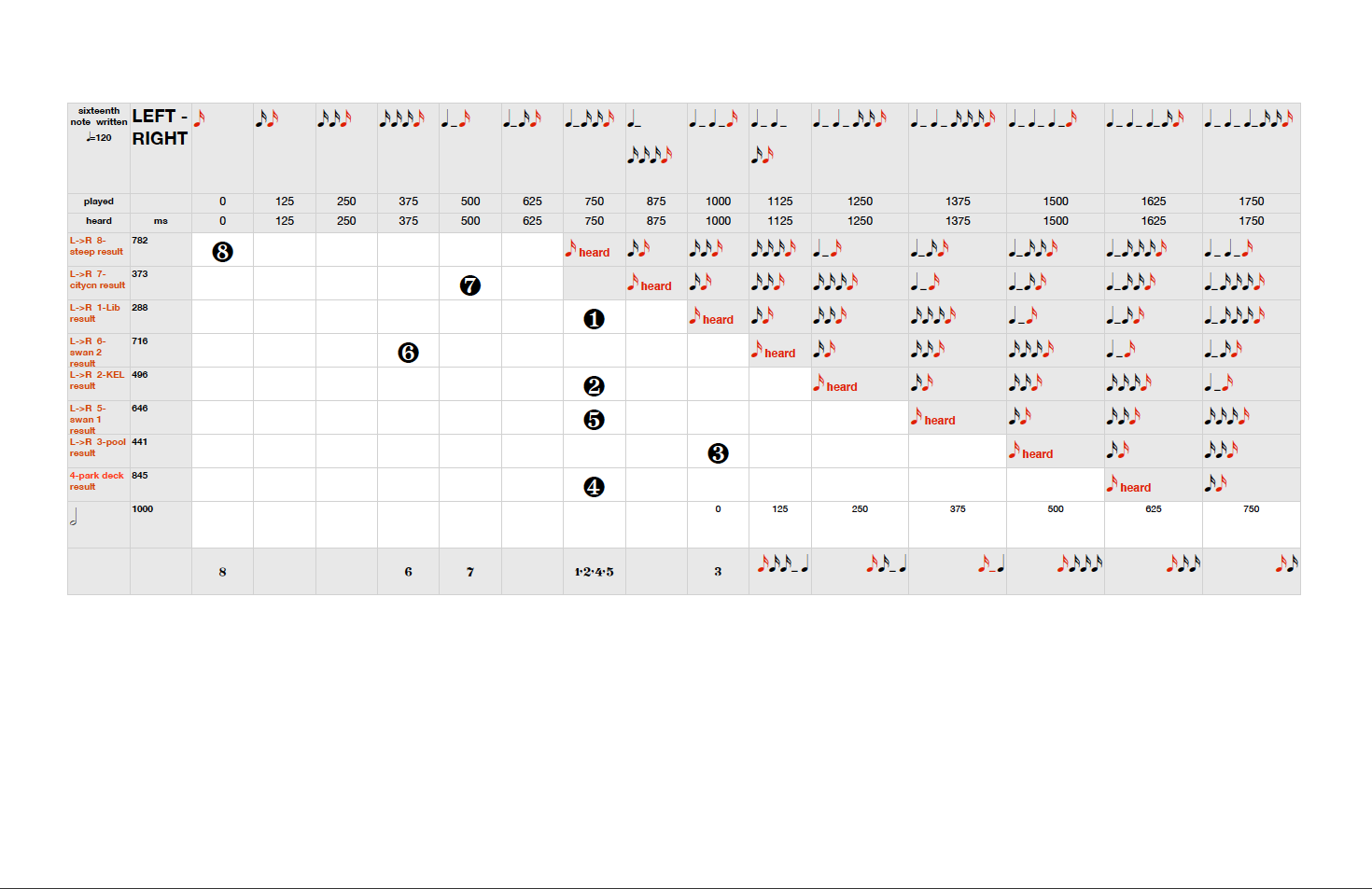

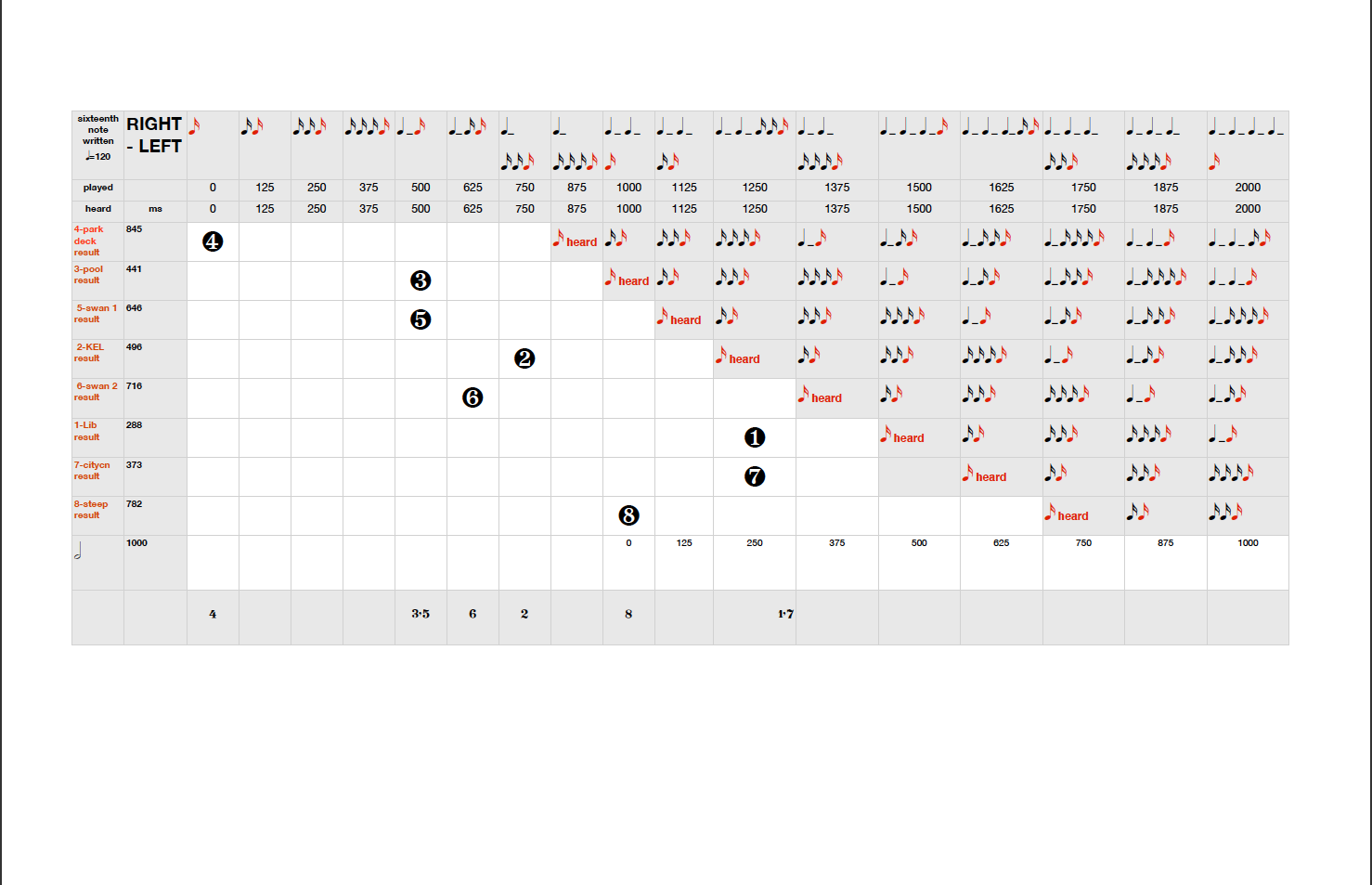

A common 4/4 time using a tempo of the 120 beats per minute was chosen. Not only was this tempo a common one, it provided a reliable timing grid for the piece with a dependable resolution of 125ms accuracy using a sixteenth note rhythmic subdivision.

- quarter note = 500ms

- eighth note = 250ms

- sixteenth note = 125ms

If a note needed to be heard at the “sweet spot” at a particular time from a particular station/location, that event had to be performed early enough to make up for the time required to travel the distance. Such back-timing of events was made possible in 125ms increments through the musical notation and shared metronome over the radios. To facilitate the composition process, matrix tables were created (included, along with other referenced material here: inSPIRE Documentation). The first matrix, called “Natural Result” displays the timing of arriving sounds from a note played from all stations simultaneously on a 125ms (sixteenth note) grid. The vertical axis is organized by the order of arrival. The left to right axis displays arrival time measured in sixteenth notes at 120bpm (125ms). The red number within the cell is the number of milliseconds of quantization error between the 16th note timing grid and the arrival time. The sound arrives before the 16th note if the number is negative and after the sixteenth note if it is positive. As is evident from the values, the available locations provided an attractive, though splotchy, spread.

Creating Antiphonal Gestures

The surround positioning of instruments around the “sweet spot” afforded many antiphonal effects. An antiphonal gesture is a resulting shape and movement of the sonic image created by the sum of sounds from different stations. The gestures could contain every station or as few as two. Gestures could be overlapped. Each gesture would be most obvious if played with loud, short durations from every instrument involved. The perspective was designed for a listener facing the city center across Rosalind Street, with their back facing Lake Eola. Audience members who decided to walk around during the performance would not experience the arrival times in these particular ‘gestures’, but would experience antiphony unique to their position. In the below matrices, the order of stations from the top of the table to the bottom lists the desired sequence of arrival times to create the effect. The red “heard” block is the time, to the closest sixteenth note, that that position would be heard from a sound played at the bold-circled time.

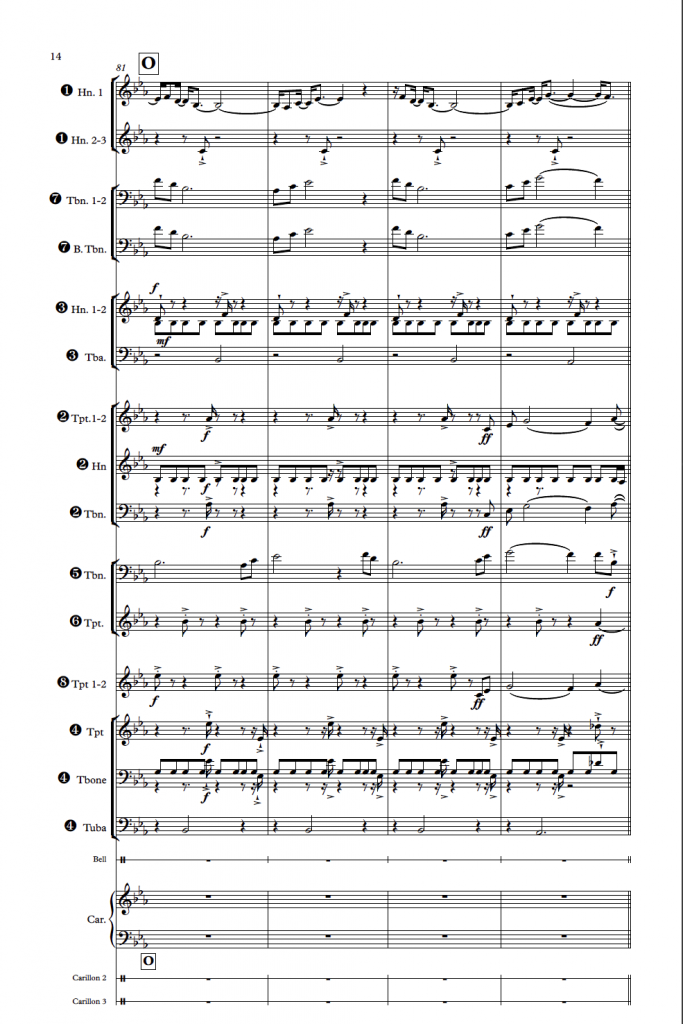

Left-Right was designed to begin at the furthest point to the left of a listener facing the intersection of Washington and Rosalind. The antiphonal gesture begins at the Baptist Church steeple (8), and ending with the Avis parking deck (4). This effect would begin with a note from the Baptist Church steeple, followed by an eighth note of silence, then a short note from swan two, followed by the City Center roof (7) a sixteenth note later, followed by 16th note of silence, followed by the simultaneous playing of a short note by the Orlando Public Library (1), KEL Tower (2), Avis parking deck (4) and Swan boat 1 (6), followed by another sixteenth note of silence, and finished with a note from The Vue high rise swimming pool (3). The result is a string of entrances from left to right. Left to Right (or Left-Right) was not used often because of the difficulty of the rhythms. Right to Left (or Right-Left) was used in the piece more often because of the more basic rhythmic playability.

The sounds of the Bell and Carillons were not used to create surround or antiphonal effects but rather for their shimmering color and psychological associations with spirit and joy. Their sound was quiet and easily lost on account of their greater distances from the “sweet spot”, but listeners walking north or west would hear them easily. In those areas, an entirely different antiphonal imaging would result from changed perspective regardless, so there was less justification to include the bell or carillon into the matrices.

Music Difficulty

The combination of antiphony, melody, harmony, orchestration and development provided a great deal of creative raw material for inSPIRE. Some of the musicians were to be college students and because I had no real knowledge of the student musicians’ abilities, the music was scored conservatively for the main body of players. Antiphonal gestures were sparsely employed. The presentation of melody and development were of a more common concern. Doubling, which lends weight and color to strengthen a melody or motive, needed to involve more than one station playing the same music in unison. But since every station was located at a different distance, doubling required timing alterations to allow for delay times. In cases where arrival times differed by less than 125ms, a unison would be blurred. This blurring effect was made interesting by differences in direction from the surround soundstage. The blurred unison could be stretched into stretto by increasing the difference of arrival times. Shifting melodies early or late by a single sixteenth note creates a difficult rhythmic passage, which was usually relegated to the more able musicians.

We had only one hour for rehearsal preceding the event (which took place at noon). The decision to use the radios to call out of rehearsal letters ensured that any musician could quickly find their way back to the correct spot in the music if they became lost. All of the musicians were instructed listen and play to the radio clicks intently, and not pay attention to the rhythms of music around them.

Instrumentation and Placement

Benoit Glazer (music director of Cirque du Soliel: La Nouba and the founder of the Timucua Foundation) and I recruited 22 excellent brass musicians for inSPIRE’s premiere. Three of these musicians are principals of the Orlando Philharmonic. Others included professional musicians from the vast Orlando theme park performers community. As previously mentioned, we also had Music students from the University of Central Florida, Rollins College, and Stetson University performing along with the professional musicians. The final instrumentation compliment was:

- 7 Trumpets

- 6 Horns

- 6 Trombones

- 3 Tubas

There were several factors that guided the distribution of the musicians, such as:

- The space constraints at each position, including egress difficulties

- The position’s distance from the sweet spot, since larger distances required greater sound power, more instruments were needed to compensate for the lost sound pressure level to create an audible sound for these stations

- Orchestration advantages

- The frequency range and construction of the instruments. The sound from cylindrical brass instruments such as Trumpets and Trombones can be easily directed by pointing the instruments’ bells toward the audience. The higher frequency range of the trumpets should be more audible across longer distances.

- Conical brass instruments like Horns and Tubas are built with bells not normally facing the audience. Horns point behind the player, while tubas point upward. The lack of strident overtones in these instruments can also make them more difficult to hear. Conical brass instruments were to be placed closer to the “sweet spot”.

- Some musicians had issues with fear of heights, fear of the water, or required special requirements because of disabilities, instrument size, or the need for a rapid exit for various reasons.

Performance Day – Surprises

A day before the performance, we learned that the “Making Strides Against Breast Cancer 5K Walk” was planned for 9am the morning of the concert. The good news was that the walk began right in front of the Disney Bandshell, our “sweet spot”, and Rosalind Avenue would be closed to traffic. This was fortunate because this would allow for the work to be heard more clearly, and in addition, there was now a possibility that more people would enjoy the experiment. The bad news was our concert area was blocked off! 40,000 attendees had planned to walk. Those 5K participants were going to be in the downtown area long before the performance, and with only an hour of rehearsal time prior to the performance, having musicians (and prospective audience attendees) struggling to find parking or navigating through a crowded downtown could have ended up being quite problematic.

Fortunately, every musician made it on time. We rehearsed for an hour, “captains” and “conductors” were assigned and Terry Olson’s well-organized team took the musicians to their stations. A crowd appeared, excited about what they were about to hear. I introduced the concept to the audience, and the music began. About 2 minutes into the work, the batteries began to fail in my radio. The work fell apart without the constant beat. Station conductors could not communicate. Several stations simply quit playing.

I replaced my radio with an unused one, and the musicians agreed to give inSPIRE a second attempt. This attempt was thankfully much more successful and the end result was a sonic experience that urges further experiments in composing Distance Music. During the performance, 8 of the 12 stations were recorded on video by phone cameras and the ambisonic recording, engineered by Thomas Todia, was a success.

What We Learned

Distance Music works.

Antiphonal gestures are effective in Distance Music composition.

Stations playing in front of reflective vertical walls had a huge sonic image compared to those that did not. For example, the 4 horns at station 1 were significantly louder than their closer proximity would suggest. The brass players on the KEL Tower were backed with vertical surfaces of the building and were very easy to hear as well, creating a large sonic image.

Wind played a role in attenuating the sound from farther stations, especially from the farthest positions of station 4 and the Carillon from Trinity Church.

St. Luke’s Cathedral bell was barely heard at the “sweet spot” during the performance, though church members reported that the musical content was clearly heard by residents past the east boundary of Lake Eola, and at other locations several miles away.

Composers of modern, ‘difficult’ music sometimes criticize audiences for lacking interest in what they painstakingly create. In reality, there are many people who want to engage in the music and make efforts to understand how to listen. People do understand the nature of sound and acoustics at a basic level and, in the case of this project, were excited about the work because they were informed through previous announcements about its goals and theory.

What To Do Differently Next Time

The next Distance Music work will employ more antiphonal gestures. These proved to be more successful than I imagined. The initial reason that fewer of them were employed during this composition was due to the level of rhythmic difficulty required to play them, though the 22 brass players had few issues reading them and in the end, I scored the music too conservatively.

The trumpet playing from the swan boat on Lake Eola was very easily heard – in fact, too easily heard. This was due to the boat captain steering far too close to the “sweet spot” than instructed, but also because the water provided a good acoustically reflective surface. The trombone on the other swan was expected to sound louder, but that may have simply been a result of the trumpet musician overblowing. The boats needed to be 700 to 800 feet from the “sweet spot” for the sonic results to be accurate, though perhaps in an attempt to help the piece, the swan boat stations were allowed to drift 400-500 feet closer to the “sweet spot” than intended. If the next work uses boats, I will take more time to instruct the captains where their boats need to be positioned. For this performance, both boats were a few hundred feet too close, unfortunately ruining the intended gestures and general counterpoint.

In my next Distance Music composition, I will include some simple antiphony of hearing each station by itself, perhaps trading a theme around. This will help define each location for the audience and strengthen the composition and experience overall.

Summary

Distance Music is a combination of art, science, and community. The audience experiences musicians performing live from surprising and varied locations, chosen scientifically, yet creatively to fuse together and create an uplifting aural experience. It is a gift to the people of a city, heard on its outdoor streets. It is an event that intrigues its listeners because it employs concepts of music, acoustics, and sound in general that are tangible and understood while encouraging curiosity about the further science of sound by presenting a different experience for every location, and each listener.

As a musical experience, inSPIRE met its goal. Though not artistically perfect in its execution/performance, the experience definitely worked symbolically, and provided a unique sound/musical experience for a city and its visitors. The end goal was to compose a piece of uplifting music, played from ‘on high’ from places of worship and towers of industry with the intent to inspire optimism and community from those listening, and in the end, this goal was fulfilled.

A video of the event is available at www.keithlay.com/works

very cool Keith. very inspiring work.

I didn’t take your music history course at Full Sail about a decade ago because I had placed out of it but I remember the few conversations we had and felt strongly that you were one of the more powerful and inspirational forces at FS. Keep teaching those kids what’s good for them. :)

The video will be up Tuesday evening August 6

The video of the event is now online!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJ9aXLzaiuM&feature=youtu.be

This event was one of many amazing compositional works from my friend Keith Lay. Thank you for letting be part of it Keith, we need as much of this kind of thinking as possible.