Guest contribution by Guido Helbling

Don’t worry, I won’t bore you with a treatise on acoustics. But multi-channel impulse responses can often create problems between individual channels (e.g. over-emphasised frequencies and phase cancellation), so it is worthwhile to analyze one or two such situations.

Analysing Sweeps

A quick recap on impulse responses: an impulse response is captured by playing back a sweep signal through a speaker. A closer inspection of the signal reveals all sorts of information about the acoustics of a room – or its ‘soul’, if you will. :-)

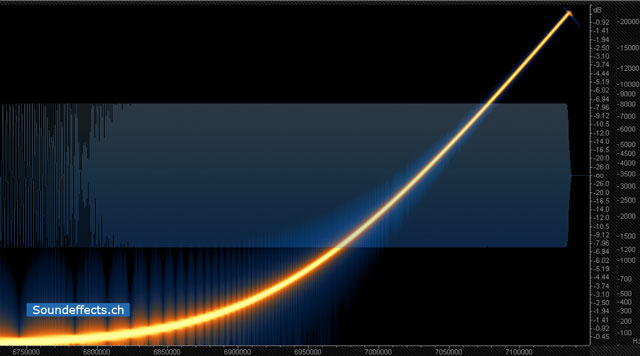

I have a more detailed explanation of sweeps on my website, but for this article, let us look at the spectrums and waveforms of recorded sweeps to understand the problems that can arise:

A sweep is a signal that rises uniformly over the frequency range of 20 Hz – 20 kHz with the same audio level, as shown above. If the signal is now played back and recorded in a room, you can see the effect of the acoustics of the room on our beautiful clean sweep:

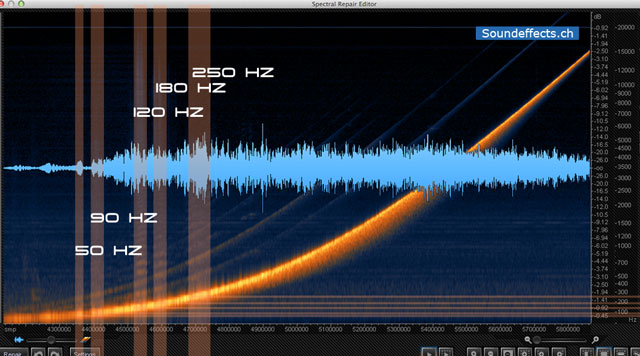

Sweep 1: Sweep with significant room modes

The perfectly shaped computer-sine-body has turned into a fully grown sine sweep, warts and all. Seriously, Sweep 1 is a very even and balanced sweep with beautiful reverberation, which you can clearly hear and see from the signal in the spectrum.

Notice the resonances in the bass range, particularly the clanging at 180 Hz? The dimensions of every room can create acoustic problems, here we can safely say that the room produces a distinct resonance at 120 Hz. This does not mean anything negative for our impulse response – on the contrary, in fact. Our impulse response is a fingerprint of the room we want to copy, and therefore includes the room modes. These rumbling frequencies are not too intense, indicating that they belong to the natural character (and peculiarity!) of this room. However, if they occur too strongly it might be worth changing the position of the microphones – or, alternatively, reducing the playback volume of the sweep or tweaking the sweep in post-production.

These room resonances are very peculiar. The peaks that we see in the spectrum (clearly audible in the recording) are in proportion to each other: the first resonance occurs at approximately 45 Hz to 50 Hz, the second at 90 – 100 Hz, followed by 120 Hz, 180 Hz and 250 Hz.

90 Hz is a doubling in frequency, i.e. an octave, of 45 Hz. A particularly strong resonance appears at 180 Hz, which is an octave again from 90Hz. Also, the resonances of 250 and 120 Hz are in proportion to each other – being one octave apart.

Sweep 2: Restless sweep with all sorts of resonances

Sweep 2 is very quiet in the bass region, but includes clear resonances in the midrange. It hints at a rather small space, whereas sweep 1 above originates from a much larger space.

Problems?

When recording impulse responses, it is unfortunate that you can only analyse the sweeps after they have been recorded, and more critically in a studio. This is usually when problems and ‘strange phenomena’ are noticeable. But by then it’s too late for adjustments and corrections, as they quickly become time-consuming and complicated, resulting in unusable sweeps. There goes all your hard work!

But with the right precautions, this can be avoided.

Coping With Phase Problems

Sweep 3: Stereo Rear-Channels with phase problems

When an impulse response creates a reverb with a negative phase, it should be used with caution. Especially in audio post production and surround sound applications, this is undesirable since down-mix versions cancel negative and positive areas resulting in sounds ‘disappearing’. This is an unpredictable phenomenon and must be prevented; hence negative phase angles should be avoided. I have despaired over phase problems between the individual channels many times in post-production. Dozens of tracks ended up in the bin because they were simply not phase-stable enough.

Basically speaking, if phase problems occur between the individual sweep channels, you can be sure that the same problem will happen with the converted impulse responses. In the example of Sweep 3, you can clearly see how the phase meter moves into the negative range in the bass region. It is very important to prevent this during recording.

Causes of Phase Problems

It is important to investigate the cause of these problems. In the above example the phase problems occurred randomly and were frequency-dependent and could be caused by:

- phase problems due to unfavourable microphone positioning

- technical problems (badly soldered cable, reversed channels etc.)

- an acoustic cause

Phase problems due to unfavourable microphone positioning

Some microphone arrays are generally more stable and less sensitive to phase problems than others. With XY or MS stereo methods, the microphone capsules are placed directly above each other and the stereo image is created from the level differences of the two microphones. In contrast, AB microphones (or a ‘spaced pair’) create a stereo image through time delays in the arrival of a sound at the microphone. Recordings with MS or XY generally produce no phase problems.

Image above: Vertical arrangement of microphones results in additional phase equality, even if omnidirectional microphones are used. The two Neumann MS stereo microphones can be seen clearly above.

Technical errors

I never reverse channels! And anyway, MY cables are soldered properly! Or are they …?

Nevertheless, it pays to be critical of oneself and to check one’s setup.

Acoustic Causes

When recording multiple channels, as I did with ten audio channels for the Auro 3D impulse responses, I had sufficient channels to make comparisons. I was able to compare the behaviour of the phase relations between the microphones in the system. When the phase problems occurred independently of the microphone array, my long-held suspicion was confirmed: the phase problem was of ‘natural’ origin and therefore had to be recorded as part of the character of the room.

As I had a laptop with an audio interface for the playback of the sweeps with me, I decided to check for phase problems with a phase meter. This proved to be very helpful, since naturally occurring acoustic phenomena due to phase problems can be displayed easily. Naturally, using a correlation level meter is an additional step in the recording of impulse responses and it certainly does not make the workflow any faster. Ultimately, it was worth the effort to find out where problems occur and what not to do.

Avoiding Problems

Below are a few points that should help avoid most problems. Sweeps are not natural sounds. They are about as natural as the cosmetic surgery of rock stars. Sweeps have no resemblance to a violin or other instruments we are familiar with. Because they cover the entire frequency spectrum, they stimulate all the resonances in a room due to their loud volume and bring them to life. This unpredictability deserves attention.

-

Observe Sound Levels

The recording level of sweeps should be kept in mind. It is advisable to make a trial run to check levels. If the level of a sweep is unusually high compared to what is expected, it means that the microphone is picking up a resonance. This can be unfavourable and a change in the position of the microphone can remedy the situation.

-

Avoid Distortion

Overdriven sweeps are the death of every good impulse response. Distortions also invite strange phenomena and are simply unnecessary. Too little gain is preferable to too much!

In addition, different sweeps are recorded at the same recording position must be recorded at the same level.

-

Away From Walls, Columns, Corners

Columns, corners, walls, smooth surfaces etc. all create resonances, unfavourable reflections, rumbling and droning. In other words: setting up your stuff in a corner will lead to all sorts of problems. If you are looking for the extremes, the phase correlation should be checked in order to obtain a useful result (or at least a second version of a slightly off-set position should be created).

-

Look for a ‘geometrically balanced’ place

After my initial difficulties with the phase problems, I proceeded according to the following consideration: where would I set up my microphones if I was recording a musical instrument instead of sweeps? Where would I go if I would make a music recording in a concert hall? Certainly not in the corners but in the middle of the room, where a balanced sound from all sides exists. So if you want to capture the acoustics of a room, it is advisable to go where the sound is best. If you want to make diffuse recordings you should pay attention to the phase.

Conclusion

This is the first part of the tutorial on impulse responses. A second part, which I am yet to find the time for, will shed light on comparing impulse responses and how to setup microphones before recording. Naturally, I appreciate any feedback and comments!

Guido is a sound editor and recordist for feature films. He travels around the world to capture atmospheres and background tracks in stereo and 5.1. Since 2005, he runs Avosound, previously Soundeffects.ch, an online-store for sfx, sound libraries, Soundminer and SFX-licensing service. IMDB / G+