Skip Lievsay needs almost no introduction: He is one of the most distinguished and prolific sound editors in the movie business. His many collaborations with The Coen Brothers, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee and Jonathan Demme, to name just a few, are often considered classics. Lievsay has been nominated for four Academy Awards, two for No Country for Old Men and two for True Grit. He is a New Yorker but has been working in Los Angeles for several years. Recently, he moved back to NYC and talked with Designing Sound at a new Warner-sponsored sound facility on Manhattan.

Skip Lievsay needs almost no introduction: He is one of the most distinguished and prolific sound editors in the movie business. His many collaborations with The Coen Brothers, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee and Jonathan Demme, to name just a few, are often considered classics. Lievsay has been nominated for four Academy Awards, two for No Country for Old Men and two for True Grit. He is a New Yorker but has been working in Los Angeles for several years. Recently, he moved back to NYC and talked with Designing Sound at a new Warner-sponsored sound facility on Manhattan.

DS: Skip, thanks for taking time out to do this.

SL: My pleasure.

DS: The theme should be: Music and sound design. And I wanted to start out by asking you about your background. Are you a musician yourself or do you have a musical background?

SL: I started playing in rock bands when I was around 10. And that carried through high school pretty much. And I have some instruments that I play every other day. I started out with the guitar. And in my band they already had a guitar player, so I switched to bass. And like all great sound people I still play bass. I couldn’t say I’m a musician. I’d say I’m a dabbler more than anything. It’s entertaining and I enjoy it, but I don’t… To say I was a musician would defraud people like Terence Blanchard and Miles Davis.

DS: How do you feel that music has changed its role in movies during that period of time? Do you feel a change has happened?

SL: I’ve had a lot of discussions with Howard Shore. We’ve talked several times about the idea that movies really are a kind of more public and accessible version of opera. And that the combination of image and sound is something that movies owe a lot to opera, particularly Mozart and the operas that were done for the masses. Movies I think are a direct lift from the operatic experience.

I think in those terms you can’t really have the drama without the music, whether it’s connected to the picture and the story or superimposed like a score, I think it’s a grand alliance between the drama and the storytelling and the fantastic musical underpinning. I think it’s a lot like memories, you know… Things that we know are stored in a place in the brain, and you can tap into them with imagery or a suggestive track, but you can also tap into memories and into deeper emotional contexts with music because it’s stored in a kind of mysterious part of the brain.

DS: That’s really interesting. Those are some interesting associations.

SL: I find that a lot of the things we are called on to do is making those associations. There’s somewhere in the script where it says that there’s a sound and it’s hard to describe, and then the filmmaker says: “It reminds me of this thing I heard as a kid”. And they can’t give you much to go on, and you’re kinda stuck with, you know, just the three of you, you know… Me, myself and I trying to figure out: “What does that mean?” And a lot of times you’re forced to go over there, to the dark corner, and open the door and see what you see. And a lot of times it has a musical context.

DS: I sometimes feel, when I listen to modern music, that it feels like they don’t have to play by any rules, and sometimes that’s extremely liberating and inspiring. And…

SL: Are you talking about Brahms and Schoenberg or are you talking about Trent Reznor?

DS: Well, maybe even both, in a way. I mean Stockhausen and Steve Reich and Trent Reznor… It’s all about throwing out the rulebook in a way. And sometimes… In films it’s very rare that you get that.

SL: Yeah, you’re absolutely right, and it takes a pretty bold head to want to leave the comfort zone of the symphony score and experiment with something that’s outside of the box. I worked on a movie last year, and it takes place in space. And the director, he’s a really interesting director, his command to the composer was: “It can’t sound like a symphony score”. So they did a combination of sound effects and sampled sounds and then we also went to Abbey Road and recorded a symphony score in a kind of traditional way to picture as a standard symphony arrangement, which they then took and manipulated and processed and removed the kind of… the “honey pot” from the deal and made it a more sort of aggressive thing, and they successfully transformed it and at the same time they made use of the lush underpinning of the orchestra’s sound. That’s really bold and cool, and it works so well in the movie.

DS: What movie is that, Skip?

SL: It’s Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. That’s coming out in the fall this year.

DS: I’m really, really looking forward to that.

SL: It was a great experience. He’s a fantastic director. I was the dialogue and music mixer and we mixed it at De Lane Lea in London.

DS: I’m really looking forward to it. How about you yourself? Do you use music as an inspiration for your work?

SL: Yeah, in a way. I find myself sometimes drifting into a “composer envy”, thinking of things… I’ve done this. I’ve put the music to pen and done some recordings for films, and I find that to be satisfying. But I don’t really have what it takes to be out there on the bleeding edge of composing, so I don’t really want to do that, and I don’t want to take anything away from Carter Burwell or whomever. But I did work on a film a couple of years ago, and the temp-score wasn’t coming together, and I got inspired and made some cues, and I worked with a friend of mine and we made some very cool cues for the film. It never really went anywhere, but it was still very satisfying and fun. And actually I used some of those cues for a kind of soundscape sort of thing for the Coen Brothers’ film Inside Llewyn Davis which is coming out in a few months.

DS: Wow.

SL: I’d have to point them out to you, because they’re not very obvious. But once you know they’re there… That was fun to do. It was nice to have some of the stuff I did actually end up in a movie. I don’t really aspire to that and it’s way beyond my technical skill. And the last thing the world needs is another composer who doesn’t know how to write music, so….

DS: But I’m also thinking about your sound work. Because so much of the way you use sound is done in very musical ways. Instead of maybe playing the guitar you’re using the sound of crickets, instead of using the drum you use the sound of typewriters…

SL: Yes, I think I know what you’re saying. And boy, I’ve been so lucky to have these opportunities. First off: You can’t, as they say, make a purse out of a sow’s ear. You need to have the opportunity first. And then you have to have the patience to figure out what it is you really need to achieve, and then you have to have the focus to take the elements that aren’t logical and put them together into a logic of your own design, and then have something good come out the other side. And I gotta say that over the years I’ve worked with directors who understood that – either very directly or innately. That’s what frees the sound from being sound and turns it more into music… the fluidity of not being enslaved by the actual picture edits.

I was working with Terrence Malick on The New World, and it had a sequence where the ships are arriving at Jamestown for the first time. And they’re sailing up the river and Pocahontas sees them for the first time. We’re cutting back and forth between these various perspectives of her seeing them and down-angle at the river and then Colin Farrell is in irons in the hold of the ship and he can sense that something’s happening and they’re not at sea. And he finally comes up on deck. And the shifting perspectives were fun, because we went from the forest to inside the ship to on deck, and that was all good… And then gradually when the ship landed, and they come off the ship and they come into the fields and grass and lush, verdant Virginia forests… Terry said, you know…. We had all these beautiful sounds here, but they have this harsh editing in them because we’re going back and forth from location to location. And he said: “Let’s do an experiment where we turn off the projector, and we have the sounds that we have, and we don’t make the sounds adhere to the edits but let the sounds have their own natural ebb and flow. And let’s think of the whole sound, everything that’s playing…” The music, which was that Wagner nonsense… And, you know, the specific sounds of the grass, wind in trees, footsteps and things like that. “Let’s let them all go as if it was a river of sound, and the individual parts come up to the surface and then gradually seep back down again, and have literally like a composition of these sounds sort of swimming together in the water”.

I was working with Terrence Malick on The New World, and it had a sequence where the ships are arriving at Jamestown for the first time. And they’re sailing up the river and Pocahontas sees them for the first time. We’re cutting back and forth between these various perspectives of her seeing them and down-angle at the river and then Colin Farrell is in irons in the hold of the ship and he can sense that something’s happening and they’re not at sea. And he finally comes up on deck. And the shifting perspectives were fun, because we went from the forest to inside the ship to on deck, and that was all good… And then gradually when the ship landed, and they come off the ship and they come into the fields and grass and lush, verdant Virginia forests… Terry said, you know…. We had all these beautiful sounds here, but they have this harsh editing in them because we’re going back and forth from location to location. And he said: “Let’s do an experiment where we turn off the projector, and we have the sounds that we have, and we don’t make the sounds adhere to the edits but let the sounds have their own natural ebb and flow. And let’s think of the whole sound, everything that’s playing…” The music, which was that Wagner nonsense… And, you know, the specific sounds of the grass, wind in trees, footsteps and things like that. “Let’s let them all go as if it was a river of sound, and the individual parts come up to the surface and then gradually seep back down again, and have literally like a composition of these sounds sort of swimming together in the water”.

And it was like… Oh my god, there is such a release to it, where you don’t have to service an edit in the picture. The sound has a life and a path of its own, and the freedom of that was fantastic. And I think that’s it, I think that’s the key and I’ve been lucky enough to do that on several movies. It’s the door that you need to open and pass through to have access to that musical part of sound effects.

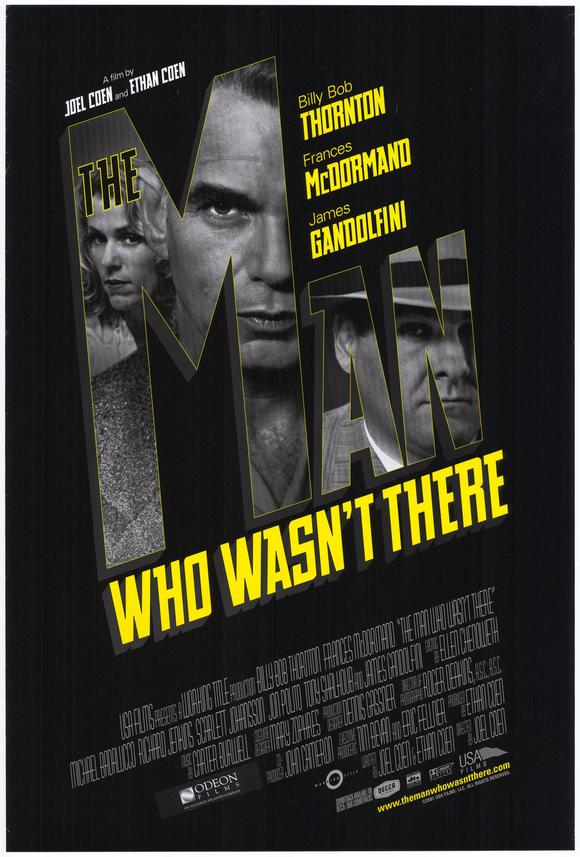

DS: You mentioned the Coen Brothers earlier and I’d like to talk about your collaboration. I think pretty much all of them have very musical elements in their sound design, but one film I haven’t heard you talk about much is The Man Who Wasn’t There. For me, the way that the voiceover works with the different sounds of the barbershop and so on – a lot of that is almost like music in itself. Maybe you could talk a little about that?

S: I love that film. I think that film and No Country for Old Men and probably Barton Fink were examples of where we had opportunities to have a score like a payday and we really rang the register. We thoroughly vetted the ideas and we made stuff that really, really worked for the film, and we got into the nitty-gritty and we found out, like, little subtle things that we could change to make the thing cohesive and deliver the ideas so that they would be accessible.

S: I love that film. I think that film and No Country for Old Men and probably Barton Fink were examples of where we had opportunities to have a score like a payday and we really rang the register. We thoroughly vetted the ideas and we made stuff that really, really worked for the film, and we got into the nitty-gritty and we found out, like, little subtle things that we could change to make the thing cohesive and deliver the ideas so that they would be accessible.

That film is one of my personal favourites in terms of the mix. It’s such a great combination a really interesting voiceover, a fantastic sound to work with, and beautiful music. Beautiful Beethoven, which works beautifully with the picture. The music is really well-applied. It’s an interesting thing that it’s operatic and things are expressed musically throughout the film, but it has the voiceover which is more of a storytelling idea. So it’s kind of a dual film, in that it’s a person telling you a story, but it’s kind of operatic, sort of like a symphony, I guess, with various movements.

And I just love the film. It was actually known as The Barber Movie until the very end. And we finally came to the end and the studio went: “Well, what’s the name of the movie”? And Joel and Ethan said: “Well, it’s called The Barber Movie. What do you mean?” And they said: “No, it’s not called The Barber Movie. We’re not releasing The Barber Movie.” And so they literally sent over a packet of possible titles. And I guess there’s a program where you can put in a few words and then it spits out 20 or 30 pages of possible combinations. And that’s where the title came from.

Originally, Ed Harris was supposed to star in the film but didn’t do it. He changed his mind. And that’s when they got Billy Bob, which was, I mean… I guess that movie with Ed Harris would probably have been every bit as good and certainly would’ve been quite different, but the Billy Bob angle was a wild card really. And I’m not sure Ed Harris’ voiceover would have been as much fun as Billy Bob’s.

DS: Sometimes things change…

SL: Absolutely. Actually, when Jonathan Demme first talked to me about doing The Silence of the Lambs he said: “I got this project, this really interesting project, that I really want you to be involved with. There will be no music. It’ll just be the sound effects that you are going to make”. That movie was The Silence of the Lambs with Jack Nicholson as Lecter and Michelle Pfeiffer as Clarice. Then I got hired to work on The Silence of the Lambs starring Anthony Hopkins and Jodie Foster with music by Howard Shore. It changed. But Howard and me are very good friends. I love working with him. If I’m gonna have my head handed to me, I prefer it to be done by Howard.

The Silence of the Lambs was a very challenging piece of work. We had a fantastic time and it was very difficult for him because the editor and the producer and the mixer were very classical in their approach and conservative, and he really wanted to push out. Eugene and I made sound effects. We spent all our time making weird, wacky sounds and we had another crew just to do the ordinary sound design. Doors, backgrounds and stuff, while Eugene and I just made weird sounds.

Jonathan would have to, you know, go to battle with the rest of the crew to put our stuff in, but he really, really liked it and he convinced them all to be quiet and let him experiment with this stuff. And oftentimes that meant taking out Howard Shore’s score and listening to these sounds. And he had to endure this crush of negative vibe about… “You’re ruining the film, why are you putting all that noise in there? The music is so great.” And Jonathan, bless his heart, endured all that and managed to create a pocket for some of that cool stuff to exist.

I see Jonathan nearly every week. We had some great times together.

In the second part of the interview, Skip will discuss his collaboration with Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee – and U2!

You bastards. You’ll have me waiting to read the rest until tomorrow. That just aint fair :-)

I love Skips work, awesome!