Cross-posting from personal blog.

I’ve had two ideas take obsessive root in my brain recently. They’re not new concepts, nor are they new to me. My first introduction to them was 8 years ago now, but I find myself pondering them with the regularity that my dog wants food. [Now? Now?! ………..Nooooow?] They’re worth talking about in a public space, because I hope they’ll stimulate some engaging conversation in our community. There’s also the hope that said conversation will filter and focus these ideas into greater resolution for myself. If it helps others in the process, so much the better. These two concepts, as spoiled in the title, are deprivation and barriers.

I plan to cover these ideas over two articles. In this, the first, I’ll lay out my thoughts and musings on concepts introduced to me through the writings of Walter Murch and Michel Chion. They are two different arguments, yet I feel they are closely related and augment one another. In the second article, I’ll examine several scenes under the frameworks I present here.

The concepts (paraphrased):

- Deprivation of sensory information causes the viewer to extract greater meaning from art. (Murch)

- The Voice defines the barriers it transcends. (Chion)

Let’s begin with Walter Murch’s argument.

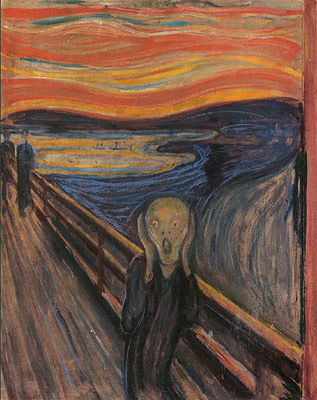

This idea of his is one that I’ve seen pop up in several places. There’s mention of it in an article on FilmSound.org, in the foreword he wrote to the English translation of Michel Chion’s Audio-Vision…in fact, I’ve lost count of the places I’ve seen him mention it. His argument stems from the idea that the more traditional forms of art (writing, painting, sculpture, music, etc.) are predisposed to stimulating a greater sense of meaning for their audience, due to the fact that they are deprived of a broader set of sensory stimuli. As an example, let’s take a moment to look at Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.”

- Obviously, our example is a painting…art which contains only visual information. We have no acoustic information to work with, but we can extract impressions from the image. Beyond the explicit screaming character in the foreground…there is the indication of water and boats in the background, the walkway appears to be wooden, it is either dawn or dusk, and there is a pair of figures that share the space. All of these elements help us to mentally fill in the missing sensory information. We personalize the painting for ourselves, imagining: the timbre of the scream, what the surrounding space may sound like, or how the figures in the back left react to this vocal individual. Thinking about it further, would you actually imagine the foreground character screaming if the painting were not titled “The Scream?” We may find paths to multiple meanings and scenarios through these musings.

Often times, artists have a meaning that is embedded within their work, but that is merely their intention…their interpretation. One of my professors once said, “If someone identifies a meaning within your piece, it doesn’t matter if you intended it or not. If it can be found, it’s there.” Interpretation of art is a purely subjective act, and we draw our own conclusions…sometimes independent of those around us, sometimes considering their perspectives. If “The Scream” was a piece that provided more sensory information, there would be less room for individual interpretations as to its meaning. The more we know about the piece or it’s creator, the closer we may come to its intended meaning…but that makes it less personal. The less personal (or individual) the meaning, the less weight it carries for that individual.

Back to Murch.

We were talking about this idea that deprivation of sensory information can generate greater meaning and depth in a piece. This is where he points out an inherent weakness of film (post “The Jazz Singer,” 1927) as a medium. We have the ability to provide more information to the viewer, because we can present images, sounds and music. The combination of which can leave very little room for interpretation. [Let’s hope things like “Smell-O-Vision” never become part of mainstream media production.] Now, you may be arguing that while we can do this, not everyone does. As with many things in our industry, he’s still way ahead of you…as he acknowledges that this is more of a tendency than a “Truth.” He is merely trying to point out that we have the ability to create greater depth by choosing what to present and what not to, and that better stories leave gaps to be filled in. It can be by presenting less than the image, more…or something that is altogether different…that depth is created.

This is where Murch’s idea begins to tie into Chion’s. The concept of deprivation in a film or audio-visual piece can be a tool within the narrative, not just its construction.

Chion introduces his concept of voices defining the barriers they transcend in his book, The Voice in Cinema. This is a somewhat narrow view, as I feel it can be applied to any sound that is obstructed in a story-telling medium. This is something different from the idea of sounds defining the “space” which they occupy. Sounds do define the phsyical and objective traits of a scene, but they can also define the perceptual and subjective traits of a scene. That subjective space is where we will find the barriers. A barrier can be any number of things: a physical object, a medium, a biological impairment, a mental or neurological process or a metaphysical concept.

Let’s consider the scenario of a sound emanating from the opposite side of a wall. If this were a clean sound being cut to picture in post-production, it could easily be filtered to provide a response that is natural to the real-world. In this case, the sound is defining both the physical space (that which it is occupying in a different room), and the physical nature of the wall. What if that sound were not filtered to mimic traditional physics? What would that do to your interpretation of the wall? It certainly wouldn’t be defining it’s physical characteristics anymore, but it would still be providing a definition regarding the separation between the two rooms.

This is where the two concepts begin to converge. We will still derive meaning from this “sound in another room” scenario, but the meaning will depend on what other information is present in the scene. Barriers afford us the opportunity to deprive information.; they can define what is constrained. Likewise, identifying what is deprived leads to an understanding of the nature of a barrier. They are not equivalent, but they are complementary. We have the opportunity to define one in terms of the other. These ideas provide a means for analysis…just another pair of tools in your box of aesthetic and story-telling techniques.

How can you use them to help define sound’s purpose within the narrative and contribute depth?

Comments and discussion are encouraged. I will be working on a follow up post, examining scenes from audio-visual media with these concepts in mind…though it may take some time. ;)

I am glad you decided to post this if it has been in the back of your head for a while! And what coincidence for me, because at the moment I am working on a cartoon pilot and I found myself finding a barrier – here with the director. The cartoon is simple, its 2 characters, 1 is an evil-doing armadillo and the other a conscientious, righteous little bear. The cartoon is aimed at 3-5 year olds. Through the episode the Bear keeps finding helpless turtles lying on their backs, and he helps them by flipping them back, until finally glimpses the Armadillo flipping them. When he runs up to the Armadillo and starts lecturing him, he starts laughing – to the point the flips himself on his back and then needs help as well… Simple, but my problem here was, I was trying to create the voice/utterance for the Bear – for the Armadillo was easy a squeaky MUAHAHA evil-wondering emperor wanna be – and nothing was fitting, until I realised that maybe I should leave him without any utterance or defining timbre/traits.. Maybe it would leave the children with space to fill in their imagination the way they see, as the character is supposed to be a role-model, it would allow a greater number of viewers to relate to him – I wondered optimistically.. After reading this article, I just grasped a bit more confidence in it, and maybe the right set of words. Now the real challenge – convince the director.

Thanks mate!

Adam, I’ll play devil’s advocate for you here. You started off describing a creative barrier, which is something different from a barrier within the narrative. Depriving the bear of a voice could be the right decision (I haven’t seen or heard the piece you’re working on to know), but what might the repercussions of that idea be? How does that then characterize the bear? Does stealing the bear’s voice, the character who is doing the right thing, lessen its weight? I’m no child psychologist, but that could be a very important issue in this scenario. If you decide to follow this idea, make sure you have some solid logic as to how a mute bear enhances and drives the story. Otherwise, arguing that you want to leave space for children to use their imagination may come off as an excuse to avoid working through a creative block. Good luck!

I recommend a new book that has nothing ostensibly to do with sound, film, or media, but has everything to do with the tendency of the human mind to construct stories based on limited input, often very limited input. The book is called “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” It’s by a psychologist named Daniel Kahneman, who won a Nobel a few years ago in Economics.

One of the many fascinating conclusions he comes to after conducting and studying an amazing array of psychological experiments over the last forty years is that our ability to construct meaningful stories in our minds from our experiences is actually inhibited by the input of too many details. In other words, a few clues will stimulate us to construct a story that is plausible and meaningful to us, whereas a large number of clues will confuse us, overwhelm us.

I think this relates directly to the notion that a careful withholding of information in storytelling teases the audience into greater participation in the storytelling process.

Randy Thom

Thanks for sharing, Randy. Anything that makes us better story-tellers (even just better informed story-tellers) has plenty of relevance to sound and what we do.

Great article, and I am definitely going to pick up the book that Randy mentioned as well. I constantly refer back to the Do Long Bridge scene from Apocalypse now (which is relevant also because of the Walter Murch reference and Randy Thom being in this thread). The silence used when Roach is in the scene is amazing. I watch that entire scene as a compass to when I need to pull the sound back.

An old chinese proverb:”70 percent blank,30 percent ink, that makes a good painting.”

It’s very interesting. Maybe it sounds weird, but I have an interesting observation about this. I have a child. And I didn’t know why he was bored by some games, while enjoying others so much, so I started to “analyze” the games. Long story short, he loves every game/cartoon/activity where he must use his own imagination because there is no enough or overwhelming information given (deprivation). Whereas in any game where all the information is there, everything is given – there is no room left for his own “story” he got bored very quickly.

I know it’s only remotely connected, but still I feel it is a proof that too many sensory information can literally kill the engagement to the story. Somehow we (everyone) have to make it ours.

Shaun, I appreciate your comment, I will give deep thought to it but I can guarantee is not an excuse to avoid a creative block, after giving many attempts I keep getting that gut feeling that the right thing to do is to leave it blank, the thought here being: any kid’s voice could be his voice, and I remember that when I was a kid, even now a days actually, I’m always filling characters internal monologues with my own imagination… but as you said, I need to build a solid logic.. Maybe a very solid interaction of him and the space might be the characterization it needs.. lets see!

Cheers!

That could do it, Adam. As I said, I was just playing devil’s advocate…better to confront that idea here than with the director. ;)

Love the discussions going on here! For all of us game folk, I believe a good example of a game implementing these ideas would be Limbo. Great use of silence and subjective sound sources. I feel like as game sound designers, now is a great time for us to really begin pushing the boundaries of what is expected in a game space.

@ Mr. Thom — that reminds me of college literature classes. You get some assignments where the instructions for the paper are so narrow it’s tough to find enough space between the rules to creatively explore the topic. Conversely you can also get the “write about whatever you want!” kind of assignment where the rules are so open-ended it’s tough to know what to write. What was needed was enough framework, a “chassis” if you will, that gave the structural underpinnings onto which the creativity can be built upon. I hadn’t thought about this in the storytelling context, though, which this post has brought to my attention. However, it makes perfect sense. The viewer or listener of the artwork really only needs that chassis onto which he or she can impart his or her own thoughts.

I should add that I think the listener/viewer does need something more than the chassis of a story. They need at least a few details, a few very specific clues that are pliable enough in terms of their meaning to act like little spring boards, propelling each audience member into a journey informed by his/her own imagination. But I do also think it’s crucial to avoid supplying an overload of details, which will often cancel each other out. It’s usually not a good idea to “sonify” every single thing in a scene that could conceivably make a sound. It’s better to choose, and through that choice create a little story vector.

Randy

Great to have the ball rolling on this one Shaun!

Coincidentally, I have been reading a lot about this for the past few days and I ended up watching Alejandro Amenábar’s ‘The Others’ (2001). Much of what Murch and Chion talk about (before the digression of ideas) is very audible in this movie. Most of the soundtrack has no BGs and all diegetic elements have been mixed in to ONLY the center channel. Only during the sequences where Kidman’s character hears ‘the others’ do things spatialise in to the surround/left/right channels. The first time I heard that happen I literally jumped out of my skin! Deprivation of the senses through the careful construction of the sound track can work immensely in building suspense and tension.

It is about how much you take out and not how much you put in?

I’d argue that “what you take out” and “what you put in” are two sides of the same coin. Whichever side you’re approaching from, you’re looking for just the right amount. It’s possible to go too far in either direction. The example of The Others in this context is wonderful, but it also lends itself to analysis through another approach…developing a “language” of sound within a piece. When I say “language,” I’m referring to Semiotic construction: the pairing of signifier (or “word”) and signified (“meaning”) through collective/community adoption. I think I’ll stop here, for now, because it could easily get out of hand for the scope of the comments section. ;)

Maybe I’ll put together another article about Semiotics after I finish up with this idea…