Today we’ll be touching on the interactive side with this months Featured Sound Designer David Sonnenschein regarding his Sonic Strategies: Animal Sounds Memory Game.

This is one of many Sound Games to be created by Sonnenschein that open ears and minds to hearing the world in new ways. Focusing on the neurobiology of audiovisual input and memory, the game draws upon film and music theory, and provides one of the cornerstones for creating story, character and emotion with audio. It uses the memory flip-card model as one example of gameplay.

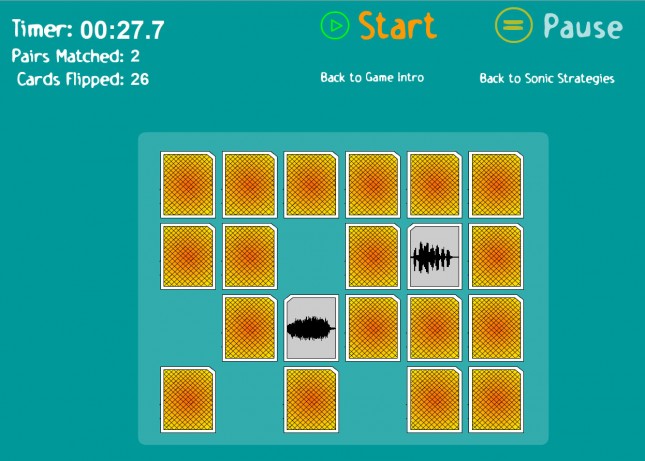

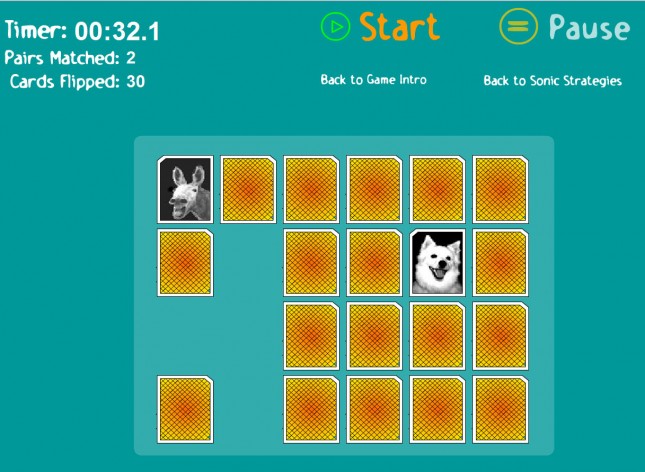

This game challenges the player to move from visual to audio awareness and memory in four variations that gradually bridge one sensory input (sight) to another (hearing). See how fast you can complete each level, and how many cards you need to turn over each time. How does your performance compare when aided by sight and/or hearing?

Have fun! See if your friends have the same or different experience. This is the first of many Sound Games to come that will open your ears and mind to hearing the world in new ways and learning to create story, character and emotion with audio.

What follows is an discussion between myself (DK) and David Sonnenschein (DS) on the topic of sound interactivity and the work he is doing to further our understanding of how we related to the world around us with sound.

DK: There’s been a lot of documentation of your work on the Sound Design side of the world in Pro Audio, but not so much on interactive media and your Animal Sounds Memory Game specifically. So let’s kick off and talk a little bit about what the chain of events were that led you to pursue this avenue and how that got started.

David Sonnenschein: It’s always been an interactive nature for me in the world with sound and so the film world in a way has constrained me in my abilities and creativity because it’s so linear and once it’s there it’s locked in place, and that’s it. Similar to my music career where I was trained as a classical musician where I played for years in symphony orchestras where you would rehearse and then perform and that was it. You were aiming for, more or less, perfection and somewhat of an interpretation in that, but it didn’t have nearly the juice that I’d get with improvisation, for example, or just jamming with other musicians. That to me was something that really attracted me so much to doing interactivity and games and all that. I’m not a big gamer myself, simply because I don’t like to sit in front of a television screen for any length of time and once I get involved in a game it’s hours and hours, so I’ve kind of held myself back from being a real hardcore gamer because I have a tendency to get addicted. Other than that I really enjoy the interactivity, so I have always wanted to get much more interactive with the sound world. This is the beginning place of where I came into it, a gut level interest.

DK: I can see how the world, the intermittency, and randomness of your experience of sound has kind of led you to this interactivity where we’re trying to, in the same way, represent this reality of randomness, so to speak.

David Sonnenschein: Yeah, and not only randomness but interactivity, where we as players as opposed to simply audience are involved, and that to me is the key to what I would like to be doing more and more. So the person is not just watching or listening but actually making those sounds happen. Sometimes it’s choosing what sounds to have happen or interacting on a cerebral level and deciding on what you’re hearing or interpreting what you’re hearing, and sometimes it’s actually creating the sounds themselves and if you’re not a musician and trained, there’s plenty of sounds we all make. So this is the basis of my interest in going into interactivity with audio.

Now specifically this game I’ve created, called Animal Sounds Memory Game, is something that’s posted for everybody and anybody. My interest in this particular game was developed with Alan Sheltra, a programmer who was a student of mine in one of my sound design programs and also had skills specifically in Flash animation and programming. He already had a game that was programmed which we adapted into this audio game. His game was a very simple card game, only visually based, and we adapted it to what is currently a four-level game. The idea of this is that we are able to play with the sounds and images, in this case using our memory, to remember where the pairs of cards are, and it starts with pure visual memory and slowly moves to pure auditory memory through four levels.

LEVEL 1 requires recognizing and remembering the placement of pairs of animal images with no audio.

LEVEL 2 introduces the sounds of the animals together with the images.

LEVEL 3 replaces the animal images with the images of the audio waveforms of the animal sounds.

LEVEL 4 provides audio only for matching pairs of animal sounds.

DK: Was this the progression of levels something that you started out with or you felt like as the project developed this was what came out of your experiments with interactivity.

David Sonnenschein: This was conceived from the beginning and I wanted to give the players a hook for transforming their memory processing from audio to visual, so I conceptualized this as a way to do it and it works very nicely. What surprises me though is that not everybody is as strong in one level as another. Some people really lock into the visual right away and then have more difficulty with the audio. Some people have a much easier time with the audio and the visual doesn’t help them, and that indicates to me that everyone has their own strengths in perceptual and memory processing. I think that was an interesting discovery, and it’s really about letting you know where your strengths are. I also discovered that little kids, three year olds and four year olds, could play this game as well as adults, and in fact, as well as some of the most sophisticated adults who are professional sound editors and designers. There are two parameters to measure “success”: one is how fast you can complete the whole game with 24 cards or twelve pairs, and the other is how few cards you have to flip over to get the correct array. You can compete against yourself to see how you can improve, but you can also compare with other people, so that gaming element is there to get people interested in trying to win in one form or another or compete with another. But it’s also there in terms of diagnosing your strengths and also improving your abilities, and so to me that was a really successful exploration. This is one of many, it’s like a pilot program for a series of Sound Games.

DK: Do you see the goal of your Sound Games as partly educational, from the standpoint of introducing people to sound, as well as helping people understand how they process things differently between visual and auditory?

David Sonnenschein: This particular game, I would say both, it focuses specifically on auditory and visual. I have other games that are only auditory games, but I would say in a broader sense I have been aiming at several different possibilities of applying this game series. I’m currently teaching an online course with the Academy of Art University in San Francisco and I created a couple of very simple Flash based games for the class in sound design. One was layering sound, which I call Sound Objects, where the student are offered several sounds that they can then combine in different manners to create different effects. Another asks them to sequence different sound effects to create stories dependent on the order, which I call Sound Events. These are very simple, but are the basis of creating more sophisticated games. In this application it’s for educational use for professionals, and students who are going towards a professional career in sound.

Another form I’ve been working on is to make this educational but for children, to basically expand their perceptual awareness. I’ve prepared a whole series of games that is more playful, let’s say for kids, to be applied at an elementary school level which would be inside of their curriculum for expanding their perceptual abilities and this correlates to the context within the curriculum, whether it’s social studies or biology or art or reading. There are here’s various ways of entering into the school curriculum to justify this as a teaching tool. In any case, there are quite a few different ideas that I’ve proposed for this, and I’m seeking funding from educational sources for this purpose. For example, teaching students the different kinds of sound qualities like volume, pitch, speed, and rhythm and how to decipher and distinguish between these different qualities and their extremes of loud and soft, and being able to use that in their languaging, being able to identify the differences between those with game play.

DK: Sure because, throughout your childhood you’re constantly trying to figure out what it means to be too loud, that’s a constant challenge growing up: what is too loud. It peaks in your teenage years when you crank your guitar amp up to eleven. Throughout that process, it would seem like a good thing to have a measure for that, and I think that’s what your proposing through these playful perceptual awareness game.

David Sonnenschein: Exactly. Another example would be rhythm, if something is ordered and rhythmic versus chaotic or arrhythmic. That’s something that a child may not know intellectually but they could feel it and hear it, and then if it’s brought to their attention through game play, like a whole curriculum called Orff which has to do with body rhythms, this can be very effective. Orff is not inside of a computer, this is using musical instruments and body rhythms and things like that, so the children actually learn how to coordinate themselves and how to communicate better, like inside of game play in the computer.

I have literally dozens of games of this nature, in a proposal for a whole series that would be for school children to learn different areas. Some tie in, for example, with reading,understanding how letters sound, or how letters look. Visually we’re playing around with fonts all the time in our computers and sometimes one font might look really different to a kid and seem like it should sound different, but maybe it doesn’t. So there are a lot of ways we can play around with sound to help kids in this area. Another one is the sounds that we make with our voice, like ‘hiccup’. What words sound like the things they described? Onomatopoeia are what they’re called, and explores the origins of language, semantic and phonetic structure, and listening sensitivity.

There are other ones that explore the understanding experience of different listening modes.What I refer to as listening modes is hearing the sound qualities of a waveform, or reduced listening, like the loud/soft or high/low pitches, or the sound source which I refer to in my classes as causal listening, what do we call it, where does it come from, what’s making the sound; it’s a dog, it’s a bird; or the meaning of the sound, called semantic listening, whether the dog is hungry or the dog is angry. Of course the meanings when we speak are all about the words too, but it’s also about the tone of our voices, so it’s teaching kids how to distinguish between different levels of listening. I could go on and on with this, but this is one area that I feel is very fertile and I’m excited to explore for educational use, for professionals and sound editors, but also for kids in general.

DK: That sounds like a great pursuit and a fantastic start to the series. Raising that awareness of sound in our lives and helping to define it for people educationally is a noble pursuit and it sounds like you have some great ideas about how people already interact with sound and ways that you can help define that for them through play. There’s so much latent learning going when we’re playing that it doesn’t necessarily have to be explicit in what you’re teaching, it sometimes creeps in around the corners, and that’s when games really succeed at teaching when it’s not necessarily being taught explicitly but just latently experienced. I think that is a side of learning that interactive really has as a leg up on some other typed of learning.

DK: That sounds like a great pursuit and a fantastic start to the series. Raising that awareness of sound in our lives and helping to define it for people educationally is a noble pursuit and it sounds like you have some great ideas about how people already interact with sound and ways that you can help define that for them through play. There’s so much latent learning going when we’re playing that it doesn’t necessarily have to be explicit in what you’re teaching, it sometimes creeps in around the corners, and that’s when games really succeed at teaching when it’s not necessarily being taught explicitly but just latently experienced. I think that is a side of learning that interactive really has as a leg up on some other typed of learning.

David Sonnenschein: Absolutely, and part of what you’ve been describing is another whole audience which is really not labeled as educational at all, but as pure gameplay. In that area I have a project that approaches this with the same elements but for a different languaging: it’s really about fun. It’s about engaging people for the interest in doing it for itself, not because a teacher told you that you had to do it. The experience of the “Ah Ha!” moment where something happens to you and you go, “Wow, that is so cool,” and that in and of itself is attractive to anybody who just wants to play. I have a background in neurobiology as well and I’m very conscious of what happens in the brain when those “Ah Ha!” moments happen and we can talk about left an right hemispheres of the intellectual and intuitive brain functions kind of joining together and bringing the player into this conscious awakening to their sonic world. That’s a really high goal of mine, to get people really into their listening powers and what they can do in their own environment and their own lives.

DK: Absolutely, and that “Ah-Ha!” moment that you’re talking about is a parallel that runs through every person, and with sound, for a lot of people, it’s very abstract when those things happen. Unless it’s seeing something happening and hearing the sound in response to seeing that, let’s say instead it’s an out-of-sight sound of a train in the distance, these kind of abstract sound experiences that we have that might lead to the “Ah Ha!” moments are a little bit harder for people to grasp. It seems like another way that we have to educate people as far as the role that sound plays in their life.

David Sonnenschein: Yeah, and putting it inside of game play is a motivation to get involved initially. If there’s something to win or something to improve upon, or some goal, that in and of itself I think is really important for any age. If you have someone who recommended it, a testimonial like “Hey this is so cool, just try it”, that may be enough to get people going and hopefully those numbers will grow. Then there’s something like Guitar Hero, which is an audio game that requires extreme skill but it starts off with people learning something very slow and it has different levels and of course it links into popular songs, so that’s really the “catch” for that game. I really find that extremely beneficial to introduce the interactivity of music to people who are not musicians so they can start doing something on that level.

One of the things that I’m attracted to as a filmmaker, director, and writer is storytelling, and that’s a whole other level that I’d like to share in this interview. All of these are little pieces of a bigger game that I’ve been formulating and developing over the years, and what I want to do is tie many of these small games together into a larger environment and gameplay so there’s a purpose to each one. In other words, with each game you can gain some more knowledge, power or tools, whatever you want to call them, to move along in the gameplay to another level.There’s a building of expertise and knowledge within the game so you can reach a higher level and experience things inside your own perceptual awareness and your own brain, but also interacting with the game itself and perhaps other players. This is a much bigger project than just the little games, but that’s kind of where I’m going with this, and like any film or game producer it requires a fair amount of structure and development and financial support, so I’m working on this as a long term project as I do with my films that require, often, a ton of money to get things going. I want to show people what it’s about, and that’s a longer term goal that I have.

DK: Sure, and these bigger projects take more people and more resources, and they become greater than the sum of their parts over time. But they’re all seeded in these little games that you’re producing and working with, and kind of rooted in your experiences with sound in our life.

David Sonnenschein: That’s exactly it, and it excites me to see the gaming world expanding and including audio more and more. I’ve been preparing the second edition of my book with some chapters on interactive media and in so doing I’ve had wonderful interviews with some of the top game sound designers. They know this stuff really well and they’ve been doing it for years and years and some of them are other featured sound designers as a matter of fact on DesigningSound.org including Charles Deenan who is one of them. We are collaborating with one another on a knowledge set as well, where is it going, not just technically, but in terms of gameplay, in terms of the ability to use technology for increasing people’s interactivity, perceptual awareness and ultimately the story, the gameplay itself. That is something where I have a very lofty goal because I use sound not just for education, and not just for entertainment, but I’m trained as a sound healer as well. When I use those words, it’s a very broad term, I refer to the use of sound for transformation, on a psychological, emotional, and/or physical level. So I would like to incorporate all of that in the game play as well.

DK: I think about the marriage of those areas in games, like you said, the diversification of games, different game types, what constitutes a game, who is a gamer and I think that all of these things are expanding and can encompass all of these different areas that you’re talking about. Whereas once upon a time games may have just represented something very playful and less serious, I think we are gaining in our ability to look at these things more as interactive pursuits, interactive experiences and with that you can tie together all of these different areas whether it’s sound healing, education, perceptual awareness, all of these things can now be encompassed in this idea of interactive experiences. I think we really are standing in a place where you can accomplish this goal of seeing those things dovetail.

David Sonnenschein: Yeah, I’m very excited about what you’re talking about. Similar to what film has been doing in terms of genres, we have extremely commercially successful films in so many different genres. Of course the more expensive ones are going to be the action flicks, the sci-fi, the fantasy and big blockbuster types. Some of the most successful have been serious dramas or ones that were family oriented, for example some of the Pixar films, which I think are extraordinary for all ages. I think that what has happened historically with games is that we’ve had a lot of teenage boy shoot-em-up kind of things, and they’re still strong, but I think they’re expanding much more into the female audience, much more into a lot of different ages, people who have been playing games for the last twenty to thirty years are ready for other kinds of games. As their own lives progress, now they’re parents with little kids, there are a lot of thing evolving in the industry itself. I’m excited to be on that interface in what I’m doing in film and joining the interactive world. I’m fairly new to it compared to people who’ve been doing it for decades. I’m extremely excited to enter in with this specific focus of audio. Another very interesting niche market is the blind audience, to do purely audio for them, and it’s a wonderful thing to see some of the things that are coming out with that and I hope that I can provide something for them as well.

DK: Right, well it’s people coming from other disciplines, like yourself in sound or in film, to the game industry who are helping, I think, to diversify things from that teenage bedroom mentality that has been somewhat wrongly shouldered with the stereotypes, which exist for a reason. I think that people have always played games but I think that electronic games have really been cultivated in the bedrooms of earth over the past thirty years, and that has certainly changed over time with the coming of casual games. I think that when people come from outside of the game industry and recognize the power of interactivity, that is helping everyone move that stereotype further into the back and bring electronic gaming or interactive experiences to a broader audience.

David Sonnenschein: Yeah, and I feel very gratified that it’s getting closer to what I said in the beginning of our talk on the interactivity with improvisation in music, and that I’m returning, in some ways, to some roots that I have in my musical background, and the feeling that, we’re using Skype right now to interact and record and there’s all sorts of things we can do all over the world interactively with people now, and talking is obviously one of them but there’s so much more. This is the world that we’re talking about today and I’m very enthusiastic for any of the readers of what we’re talking about to give feedback about their ideas on where interactive audio is going.

[…] https://designingsound.org/2011/05/david-sonnenschein-special-sonic-strategies/ – sound designer waxes philosophical. APE, SDVM. […]