Let’s get started with Tim Walston’s special month. Here is an interview I had with him, talking about general aspects of his career, his favorite tools, techniques, creativity methods, and more. Hoep you enjoy it!

Designing Sound: How did you get started? How has been the evolution of your career until today?

Tim Walston: **SNOOZEFEST ALERT!!** The last thing I wanted to do was start this month off with a big long article, but in the off-chance any of you are interested, I’ve accidentally done that. Still reading? OK here we go…

I love movies. Since I was a young kid, my earliest passions were movies and music. When other kids played with toy boats, I had a plastic shark, an unfortunate scuba diver, and a small film canister filled with red food coloring! I’ve always been especially interested in special effects: model spaceships, visual effects, prosthetic makeup, and animatronic creatures. Remember, these were the days before CGI. To this day, I prefer practical special

effects to CG, because I think you can always tell when something is a REAL thing. I mention all this because I think my appreciation for realistic things applies to my sound work. The value I place on handmade things and the merits of hard work permeate my approach and work ethic.

So I grew up making models and 8mm stop motion movies, and special effects experiments… and also playing music.

I built a small MIDI studio at my house during high school, writing and recording songs and musical ideas. I realized I had a technical interest when I found myself spending as much time programming a drum machine to sound real, as I did writing lyrics. I was spending creative energy on the sounds and production values as I wrote. This crystallized my desire to study recording engineering and maybe get into the music business.

I was a music composition major at UCLA (should have been film!). After graduating and playing in a band (like everyone else), I worked for Digital Music Corp., aka Voodoo Lab – a small company manufacturing MIDI accessories, professional guitar switching systems, and great retro style guitar effects pedals. After some personnel changes left me without a job, I figured it was time to follow my dream – music engineering!

After interning at several L.A. recording studios in 1996, I quickly got the message: There were only a handful of engineers in L.A. doing all the big records, and the rest of the guys struggled. I was going to have to get coffee and clean up the lounge for a year or so (for free) before they’d let me into the real studio to wrap cables or something. By this time, I was 27 and engaged… I needed a real job. Several of the burned out engineers told me they were thinking of crossing over into post production, saying “the hours were better and the work was more steady”. Ha! If they only knew! If I only knew!

This was, however, the beginning of a new chapter of my life: one that I had been unknowingly preparing myself for, for years. I sent out a new round of resumes, to post production places this time. I spoke on the phone to David Yewdall – a man I have still never met in person, but who helped me get my foot in the door. THANK YOU DAVID!! He recommended two names of people in post with music backgrounds, who “might take pity on me”: Steve Flick and Harry Cohen.

I made appointments and walked in to each – as green as can be. I didn’t know anything about sound editing. I just bought the sonic illusion like everyone else outside the industry. “You add the background birds, too??” I was amazed that the sounds we hear and take for granted, are so carefully crafted to sound effortlessly real.

Steve Flick showed me around Creative Café (where I first met Charles Maynes), and he talked about film theory, light and shadow. My head was spinning. Why hadn’t I taken any film classes in college!! Unfortunately, he didn’t have any openings at the time, but he invited me to stay in touch.

I met Harry Cohen at EFX in December 1996. He invited me into his sound design room immediately, and I spent the next 4 hours watching him work. He described his job, his process, his equipment, his choices… and wow, I was amazed. This is the same EFX Systems that you’ve read about in David Farmer’s interview. It was a magical place, at a magical time. As a newbie, I met and worked alongside Harry, David, Ann Scibelli, Jeff Whitcher, Michael Kamper, Andrew De Cristofaro, Mike Payne, Marc Fishman, Marshall Garlington and many, many other talented people. THANK YOU HARRY!!

I knew right away I wanted to focus on sound effects. I worked for 8 weeks as an unpaid intern, and then I was lucky enough to get hired in February 1997 to work on a small feature. At EFX in those days, all sound effects were cut on a Synclavier – basically an early super sampler/keyboard/MIDI sequencer/audio editor. We worked to ¾ video tapes. Timecode from the Video tape drove the sequencer, and we recorded the FX back to DA-88. Wow – thinking about all these old methods is a trip. It seems so primitive now, but compared to slicing up film, it was hi-tech digital audio! In the early days, I “pulled” sound effects: that meant pulling a DAT off the shelf, fast forwarding to the correct ID, and listening, to see if the effect was going to work or not. Whew!

I loved the Synclav. Any sound could be auditioned instantly on any key. It was so easy to sequence and layer sounds – so easy to perform sounds. I’ve always said that I felt that sounds on the Synclav were clay and I had my hands on them, to shape them into what I wanted them to be. (Later, using only Pro Tools and a mouse, I felt like I was trying to sculpt that audio clay with oven mits and 6 foot long barbecue tongs!) I found the sequencer aspect of the Synclav to be very familiar. Instead of a cymbal crash on the downbeat, I put a door close or a gunshot at the right timecode. My musical technology hobby had prepared me for a career I never knew existed!

I worked my first year at EFX during the night shift, and stayed extra hours to get more practice, to try to achieve the results I was looking for, and to experiment. I have hours of DAT recordings, still unloaded to this day, of various crazy noises, created with the Synclav, outboard gear and an analog mixing board. I eventually moved into a daytime slot. We worked on films, TV and video game sound. I met Charles Deenen when he was at Interplay and I designed sounds for various titles for him. In those days, I never worked as hard as I did for Charles, but I learned a lot from him. And made revisions. And more revisions…

My next big break came when I worked for Lance Brown on a show he supervised. He liked my work, and in 1999 brought me to SoundStorm to take his place as the in-house sound designer, as he transitioned to feature film mixing. What an honor! SoundStorm had academy awards! They worked on real movies! THANK YOU LANCE!!

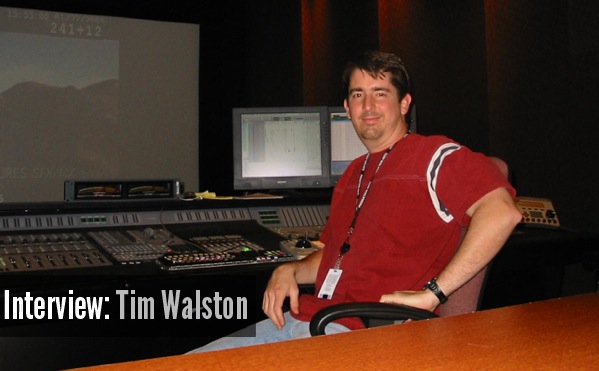

Academy Award winner Bruce Stambler helped me get into the union and now I was in the big leagues. At SoundStorm, I was lucky enough to work with Bruce, John Leveque, Becky Sullivan, Jay Nierenberg, Tony Milch, Kim Secrist, and many other talented people whose names escape me right now. As staff sound designer, I was called in to provide special sounds on everyone’s films. Working this way allowed me to focus on unique sound creation and not on the more traditional sound work like doors, and backgrounds. I was also the only one using Pro Tools at that time – everyone else used the Fostex Foundation editing system. With time, the tools, and my tenacity, I developed my techniques and created a lot of new material. This was another great learning experience and a period of creative growth for me.

SoundStorm closed its doors in 2004 while we were just starting work on “Stealth”. The show and crew officially moved to Soundelux, and the next phase of my career began. I’ve been based there ever since. With a huge pool of passionately talented people, and a multitude of sound supervisors, it feels like the future is wide open. The variety, and sheer volume of projects moving through Soundelux means an endless supply of creative challenges and opportunities.

I am fortunate to have been helped along the way by many generous people. And if any of you are still awake after reading this, then I hope that something I write this month will be helpful to you. Thank you Miguel, for extending this honor to me. I hope I can live up to it!

DS: Did you have a mentor early in your career? How was your “training” in order to enter into the industry?

TW: Harry Cohen was a key mentor to me in the early days, and he’s still an inspiration, a collaborator and a friend. Many of my colleagues from EFX and SoundStorm are now based at Soundelux, so it’s been quite a reunion. In general, I try to learn something from everyone I work with. The thing I appreciate about creative work is that there is never only one right way. I try to understand the approaches of people I admire, and then filter that information through my own methods to see what resonates with me.

My training was on-the-job experience. My musical background informs my choices, and my audio technology background enables them. As a rookie sound editor, my work was reviewed by a supervisor and then ultimately judged by the mixer and the client. If something wasn’t right, I heard about it and had to fix it right away! Working alone in the facility in the middle of the night, I had to solve my own problems. In the early days, we had no budget for custom recording, so I had to make something out of what I could find in the library. This limitation forced me to be creative with the tools and resources I had on hand. All of these experiences, and the many sleepless nights of “brute force” problem solving, have constituted my “training”. It’s important for me to note, however, that the training never stops. I never want to stop learning, and trying new ways to achieve better, or fresher results. This drive to continue my self-education and to keep growing is what keeps me coming back year after year.

DS: What do you love the most about sound design?

TW: I love the sense of creative fulfillment I get from contributing to a film. We’re making movies, man! I love to turn a silent scene (or nearly so) into one with a soundscape that brings it to life, supports and advances the story, and involves the viewer. Whether it’s a featured sound design moment like the Enterprise blasting into warp speed in “Star Trek”, or creating believable and vibrant offscreen New York city backgrounds (one car by at a time) for “P.S. I Love You”… I put the same care and effort into my contribution. When the scene plays, and the sound melts with the image, I can say – “I did that”. As the license plates around town say – I feel like I’m “part of the magic”. It’s ironic that I was so interested in special effects and monster makeup as a kid – now I get to give a voice, to those effects. Now I get to help sell those visual effects and monsters to the audience. It’s the greatest job in the world.

DS: From all the sound crafts you do (recording, editing, design, etc) what’s your favorite and why?

TW: I think pure sound design – creating new sounds – is my favorite. I love to create new sounds to put against the picture. Whether I’m trying to create a sound I imagine in my head, or whether I’m trying some crazy process or tool to see what happens, it’s all fantastic fun. Editing and mixing would be a close second, because they’re really intertwined in my workflow. I’ve always shaped the levels of my elements, and often place them in the surround sound field. The purpose here is twofold: to see how they work with each other and also to present my complete audio idea as accurately as possible. Recording is also great fun, but I don’t do it nearly enough. I guess I like them all then!

DS: How do you stay creative? Do you have any kind of methods to organize ideas and get inspiration?

TW: Tough question! Look, everyone has bad days. Creativity is not something you can always summon at the appointed time. When I am struggling with something, my only “trick” is to keep working on it. If the road you’ve chosen seems like it might yield results, then stay on it and create what you can. (I’ll discuss this in more detail later this month). If you hit a creative dead end, then try something new. Giving up will get you nowhere. I’ve found no shortcuts around creative blocks… you have to blast your way through. As they say, “Good enough, isn’t” (unless you’re out of time).

That’s not to say there is nothing you can do to help yourself. I am a creature of habit. I always start with one of the Pro Tools template sessions I’ve made. After watching a scene or a film, the next thing I do is start listening to material and pulling sounds. I create a library of sounds I think are right for the project – whether I can drop them right in, or use them as source for processing. I keep a pad of paper nearby and write down the keywords I think I should search for among my own sounds, and then the company’s library. (I’ll cover this topic in nauseating detail later this month too). I’ll also write down sounds I think should be recorded fresh, or source I’d like from foley.

With all that said, my biggest method to stay creative is not really a conscious one. It’s my internal drive to explore. I don’t want to do the same old thing on every show, that’s why I’ve sought out a creative job. I like to try new things, and to try new ways of doing things. 10 designers would give you 10 different sounds for the same thing on screen – and they could all be great. So, another habit I have is, time permitting, to try to avoid my usual methods and try something new as often as possible. I’m never 100% satisfied, so I’m constantly trying to grow.

DS: What are your favorite tools to work in the studio? Any “secret weapon”?

TW: Ahhh… gear: the thrill and the bane of our audio lives. There’s always some cool new plug-in, some new update that calls to us with its siren song and promise of sonic nirvana. I have succumbed to these temptations over the years, but I resist more often than not. Who can afford to buy every new thing? Here’s a question: Are you really a master of all the plug-ins you already have? Can you say that you know everything they can do, and that you’ve exhausted all their possibilities already? I know I can’t. So that means there’s much more to explore with the tools I have, before I lust after something new. There is a LOT you can do with just pitch change, EQ, and reverb! There – rant over. My wife won’t believe any of it, though!

As I mentioned earlier, I started at EFX on the Synclav. Then we added the old Digidesign audiomedia card with like 4 tracks or something. Then maybe 8 tracks, but we still recorded elements back to DA-88’s. At SoundStorm in 1999, I moved to Pro Tools (version 4 or 5?) exclusively. I really missed having my hands on the sounds, but I had access to an E4 sampler. The hassle of loading something into it from DAT made me do without most of the time. Currently, I’ve settled on Native Instruments’ Kontakt as my main sampler. It’s so deep I’ve only just scratched the surface. I don’t use it everyday – I don’t need to. But I have dug into it from time to time during the last few years and I’m starting to feel the audio under my fingers again.

A good library program like Soundminer is crucial to me. A convolution reverb like Altiverb, and my newest tool, iZotope’s RX have become essential, alongside the standard array of eq’s, delays, and compressors, etc. Every task requires it’s own tool, so some days I’ll reach for the vocoder, some days for the transient processor, some days for an old bit of outboard gear. I use various plug-ins from Audioease, Digidesign, GRM Tools, McDSP, Sonnox, SoundToys and Waves – nothing too exotic. Remember, it’s not about the gear – it’s about what you do with it.

Finally, my answer would be incomplete if I didn’t mention… everyday objects. Things around the house, especially kids toys, can be a wonderful source of interesting sounds. I recorded a broken music box and toy cymbals for “Nightmare on Elm Street”, a rubber bathmat for large creature movement in “Slither”, and an old trash compactor for the ship’s thruster engine room in “Poseidon”. Your most useful tools are your own inventiveness and tenacity.

DS: What would be your advice to any sound designer today?

TW: While there are more outlets for sound in media today than ever before, it seems to me there are fewer “inlets”. I started at a non-union facility. The downside was the minimal wages, but the plus side was that I got to start working on a feature very early in my career. Sometimes I’m asked for advice by beginners, and I don’t know what to say. Everyone I know has gotten into the business through a different path. I don’t know how a new person can get started today. If there are institutional apprentice programs in place today, I haven’t witnessed them myself. I’m not sure how a new talent can transcend their entry classification and move up the ladder. There’s a lot of competition out there in the form of talented, eager people. The best thing you can do is practice your craft and try to network.

<Cranky Old Guy Rant: In general, I have a problem with someone saying they just want to be a “sound designer”. It’s my opinion that anyone creating sound for picture needs to learn the fundamentals of sound editing, and the general post production workflow. You need to know the rules, before you can break them successfully. If you are going to deliver your material to another editor, or a mixing stage – you need to know what you’re doing and how the system works. End of rant.>

In summary, you’ve got to know your stuff, and understand the post production workflow and your intended place in it. This is a team sport! You’ve got to be reliable and professional. Most of all you’ve got to work at your craft: practice, evaluate, research, learn, and dedicate your energies towards your goal. If you work hard enough and follow a true passion for film sound, then you’ll find your own path in. Good luck!!!

DS: What is the most challenging project you’ve worked on, and why?

TW: It’s really hard to say, since each project has its own unique challenges. Generally, the most common challenge is time and budget. Lately, a lot of shows are lacking the time to do the job properly, yet I still strive to deliver work I’m proud of. The next most common challenge is late delivery or radical changes in CG visual effects. The final common challenge is chasing picture changes. Who am I to complain, though? These are common everyday situations and will continue I’m sure, into the future. To one degree or another, they have been part of the filmmaking process for a long time.

I will share a few experiences I’ve had on films:

“Miracle” is an incredible movie that still gives me chills. My job on that one was all the arena crowds for the various hockey games. In the first cut we received there was about 40 minutes of hockey game action! Sports crowds are very dynamic, reacting constantly as the game play ensues, and the tide turns quickly. Every player crash and turnover, each thrilling drive and disappointing miss generates a reaction. It was all painstakingly pieced together from wonderful material recorded by Rob Nokes and his crew for the film. I cut front and rear reactions, so the sound would surround the audience. There was on-camera chanting also, that had to be in sync and had to connect from one shot to another. I also staggered front and rear stereo pairs so chants would start small and loose, then gradually shift to unison as the whole stadium shouted together. The dramatic peaks and valleys of the crowds built to the ultimate roaring climax – the final game win! My virtual predubs gave the mixer lots of control if he needed it, but the shape and spatiality I intended was working really well – it was visceral. Then, they cut the game play in the film down by half… and then added the game play-by-play commentary by Al Michaels. This meant the crowd effects had to come way down to accommodate the featured dialog. Crowds in the final mix? Not so much.

“Semi-Pro” was challenging because it was just a lot of editing. I cut all the basketball action, using great wild source effects from the foley team that were recorded in an empty basketball stadium. I covered all the throws, catches, ball slaps, bounces, baskets, feet scuffs, squeaks and even the players’ run bys. It was a million little events to sync with production. It was a lot of labor, but it was very rewarding to hear the result in my room. In the final mix? Alas, not so much.

On one show, I was asked to “make it funny”… I can only do so much!

DS: What are your favorite films for sound?

TW: There are too many films! Like everyone else (and in no particular order) there’s Star Wars, Wall-E, The Incredibles, The Matrix films, Jurassic Park, The Lord of the Rings films, The Conversation, Saving Private Ryan, Amelie, Pitch Black, District 9, No Country for Old Men, Mimic, Contact, The Fifth Element, Minority Report, War of the Worlds (2005 and 1953), Transformers, Master and Commander, How to Train Your Dragon, etc.

And here’s some great sounding films that don’t get mentioned as often as they should:

Wanted, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, Stranger Than Fiction, Signs, Butterfly Effect, The Core, Silent Hill, House of Flying Daggers, Blade and Blade 2, Session 9, Drag Me To Hell, Kill Bill, The Strangers.

DS: Are you currently working on something? What’s next for Tim Walston?

TW: On January 3rd, I will start on a new feature film that I haven’t seen yet. I will also be working with an experienced supervisor that I have not worked with before… everything will be a new adventure, and a new challenge. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Great interview! I’ve alway thought House of Flying Daggers sounded incredible. Can’t wait to read more!

hi Tim. Reading about your experiences working on game crowds for “Miracle” threw me right back into my having the same assignment on “Rollerball”! We shall be brothers in crowd cutting. Sincerely though, it’s always a pleasure to hear what you’ve come up with so keep going!

“Your most useful tools are your own inventiveness and tenacity.”

well said!

Thanks, guys! Gosh, I didn’t think anybody would actually READ it!!

“cranky old guy?” Tim your not THAT old…

Great article!

Rock on Tim!!!

Really interesting read Tim, thanks.

I’m getting flashbacks from those pictures!

Great Words Man! I really felt the passion you have for sound design. thanks for taking the time to do this “big long article”. Also thanks to you Migue for bringing us this interview!

Wow! What a great interview man! I really appreciated this, so thank you for posting and sharing your insight- specifically the comments on exercising your creative muscles were excellent and inspiring…

My question is concerning the actual dynamic of working on the sound design for features..(sorry this is a bit long)

As more creatively stimulating movies hit the big screen and appear to be welcomed by the masses – titles such as Black Swan, Shutter Island, Inception etc.. the attention to sound design as a creative vehicle for story telling comparable to video, seems to make itself more known.

My question is weather or not you have seen any kind of shift in the relationship between directors / production companies or houses working with directors and producers etc. to really explore the creative possibilities of sound (to really help tell their story!).

It seems like Wall-E and other animated shorts, the sound designers are brought in much earlier out of necessity, but I’m curious as to weather or not this is done very often in your experiences. How often do you get to really work with directors? How often are sound designers consulted for their creative input in the direction of a movie? How do you know your work is fulfilling their expectations, and when creative liberty of a sound designer is taken, how do you present these ideas to the director?

Sorry that turned into many questions, but workflow in my mind extends outside of the production of sounds, and even into working with your clients to deliver the sounds you ideally want to be heard – so yes.. any insight to your experiences would be awesome!

I let this interview simmer for a little bit and had one more question. You mentioned the importance of a program for working with your sound banks, but I am curious – for someone starting out and working on developing their own sound libraries, do you have any insight into digital asset management; naming conventions organization etc? I think the programs are great, but when it comes to naming your files from recording to working with the assets, do you have any tricks, tips or insight you could give?

Thank you!

Synclavier! I still use one every day. Amazing machine for music, and even better for sound design.

EFX systems rings a bell. Did you work with Terry O’Brite?

I went to Full Sail with Lance in the late 80’s. Great guy.

Thanks for the article.

Bill T

Thanks to all who commented! I’ll answer all your questions at the end of the month.

I’m sorry to articles have been so sparse. To the Star Wars fans out there, let’s just say that certain “imperial entanglements” have become part of the process. I’ll get more articles posted as soon as possible.

To Bill: I’m sorry I don’t know Terry O’Brite.

Great interview and really inspiring! I’m a Sound Design student of David Yewdall’s at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts and spent this past summer sitting in with Harry Cohen at SounDelux. What a small world!