When it comes to preparing sound effects for a mix, there are lots of ways to approach things; I don’t claim this to be the end-all methodology. For this article, I’ll be slanting discussion towards sound effects, regretfully leaving out music and dialogue.

I’ll be covering two avenues of mixing: traditional mixes and Icon mixes.

OVERVIEW

The art of mixing is the art of storytelling. Many elements come together in a mix, and one of the challenges is distilling those elements into a cohesive and dramatic whole that works with the picture and story.

In a sense, the mix is like a funnel, where thousands of elements are distilled down to 6 final channels: L-C-R-Ls-Rs-Lfe, also known as the 5.1 printmaster.

When I cut, I try to make things sound the way I think they should sound. This means not waiting until the dub stage to get it sounding right. It’s best to make it sound right editorially, so that the mix can elevate the material to the next level rather than wasting time sifting through too elements to make it “play”.

This means, editorially, I hone and clean and simplify as much as possible. I also volume-graph, so everything has a nice balance and flow. Sometimes I also do 5.1 panning on my elements, for myself and for presentations that may arise before we even get to the mix. These pans are typically dumped when we bring the sounds to premix, unless we’re doing an Icon mix which I’ll get into in a bit.

It’s interesting how in recent years the lines between editing and mixing have become more blurred, to some people’s consternation and others’s joy. But ultimately, it’s all about “how it sounds” and we now have better tools enabling us to bring things closer to the end product much, much earlier than we have in the past.

PREPPING SOUNDS FOR THE DUB

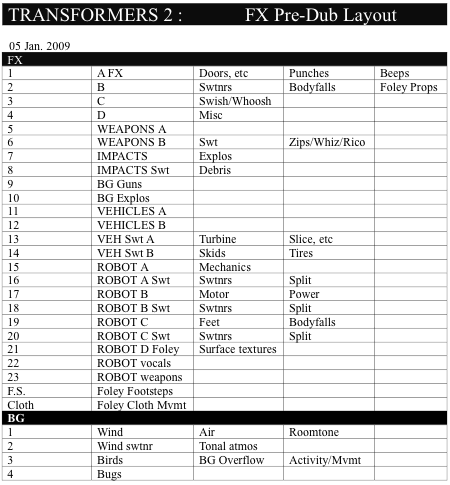

Organizing sound effects units into predub groups is one of the most important parts of making a soundtrack. If things are disorganized or grouped improperly, I don’t care how awesome your sounds are, you will have an uphill battle. It’s all about predub layout, which can be a real Rubik’s Cube of a puzzle sometimes, but which always will pay off if approached logically and carefully.

The first thing to keep in mind when laying out a predub groups is separation. Which sounds go together, and which sounds stay separate? This is important, because once predubs are mixed, if things are tied together in a 5.1, they are married forever. For example, this means if while predubbing, you mix a tire skid with your car engine into a predub, and in the final the director asks to dump the skid, you are screwed. That’s why we keep skids on separate predubs from engines, for example.

When laying out units for predub, always ask “what do I want individual control of all the way to the final mix?” Keep those elements separate. I generally think of predubs as “food groups”. Keep your potatoes separate from your sauce and separate from your meatballs and separate from your garnish.

Of course, the danger is to have too much separation, which can overcomplicate the final.

Another thing to keep in mind while laying out units for predub is the order. When mixing, you want to mix the big things first. Best to mix sweetening elements after the big things.

I’ll use some metaphors to explain the philosophy. it’s like sculpture: throw the big chunks of clay together first, and then sculpt the details after. It’s also like building a house: foundation first, then beams, then walls, then paint. Big things first, then the details.

Recently, we predubbed a dragon. In this situation, we’d want to predub vocals first, then its big footsteps, then its talons clicking against the ground. Balance the details against the main sound. As an example, in the Transformers films, we typically dubbed the robot footsteps first, then the motors and textures and so on.

Some mixers like to put up banks of four predubs at once, printing on four recorders. But generally, we’ll work a predub at a time, building mixes one by one. Finished predubs then get “hung” on the stage playback ProTools machines, so that every subsequently mixed predub can be balanced against the earlier predubs.

The ideal predub situation is that when all the predubs are finished, they can be put up on the final console with faders at unity and play together cumulatively in harmony and in the pocket. There are some effects mixers that are expert at entering a final mix with faders at unity, already balanced skillfully against dialogue.

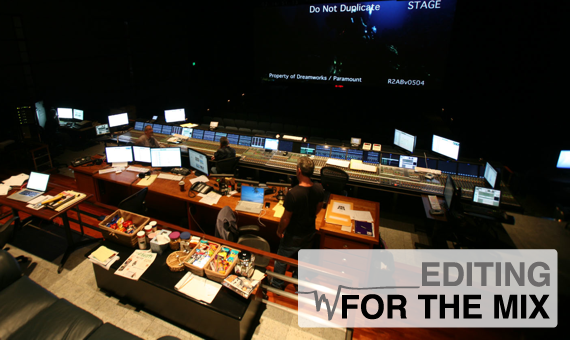

When we mix, I sit at a ProTools playback system on the stage next to or behind the console so I can communicate with the mixer. Since the old days, cue-sheets have been used as road maps for the mixer; what sounds come on what channels and when. Newer consoles have TFT displays that give a graphic waveform representation of each channel and what’s coming up. But the quickest way to get though predubs is verbally: “Goose honk, screen left, coming up at 320 feet on channel 1.”

FINAL MIX

By the time we hit the final mix stage, all of our printed predubs, now in ProTools playback “super sessions” and conformed to the latest version of picture, are loaded.

The “final dub” version of cue-sheets, also known as “topsheets” or “binkies”, serve as road maps for the mixer. These might be (rarely) handwritten, or printed on paper from ProTools dummy-regions lined up against our predubs in the super session. These days, a lot of mixers just use ProTools monitors mounted on the console, which saves a lot of assistant time and trees to boot.

While in final mode, I’m always going into our printed predub material and making adjustments. I might cut out chunks of certain predubs that clash with music, for example. Maybe certain impacts in my effects are “flamming” with music percussion, and need sync adjustment. Most stages these days have remote switchers that allow me to pull up any ProTools predub session instantly onto my screen for a tweak.

In the final, these predubs all combine to create a “stem”: the combo of all the predubs.

On a final, I also have a sound effects ProTools “fix rig”, chasing to stage timecode and outputting to the board. I have a search engine and all my design tools at the ready. If a fix is needed, I’ll go offline, throw on my headphones and cut a fix. This fix will either get recorded into the FX stem with everything else, or more commonly, go onto an additional “sweetener stem”. On the Transformers films, I had an additional off-line ProTools design rig in front of the console, because when the fix rig is in chase I can’t be cutting new stuff at the same time.

ICON MIXING

Both Malick’s “The New World” and Bryan Singer’s “Valkyrie” were mixed on an Icon console at Warner Bros Stage 6. Since it utilizes the powerful editing and automation-conforming capabilities of ProTools, it’s a very useful tool for films that have extended temps and final mixes that keep coming back.

While editing, I’m often doing a lot of 5.1 panning in ProTools to get things working in the editing room and to present our track to filmmakers before we reach the mix part of the process. All of that panning, sometimes pretty intricate, is typically dumped when we hit the predub stage. This is often fine since it’s truly great to hear an accomplished mixer do a slick pan. But on the other hand, it’s a lot of work to be dumped. I would love to be able to send panning automation from ProTools to any traditional DFC, Harrison or Euphonix console, and have the mixer use that as a starting point to build upon. Pans could be dumped and redone, but at least all that work in the ProTools wouldn’t be nuked and disappear completely and arbitrarily. Sometimes in ProTools we can do a more accurate pan on a bullet zipping out of the surrounds, for instance.

This is where the Icon is very useful. Every 5.0 pan, every send, every compression automation is retained through the entire process, even for a reel rebalance, for example. During a final on a traditional console, your fader, send, pan and EQ automation are the first things to go in a rebalance. On the Icon, not a problem.

On traditional consoles, if there are vicious version changes with tons of conforms, sometimes the stems and predubs can be salvaged by an editor in ProTools. Well-organized predubs make this easier. But it’s unlikely board automation will survive without severe choppiness if there are moves and shot swaps. On the Icon, every EQ sweep, every Impulse Response Reverb setting, every fade — every parameter — can be smoothed and tweaked graphically by the conform editor, before being put up on the stage. On films with many changes throughout a long final mix, this can be invaluable.

I recently worked on a film mixed with an Icon on Stage B at Audio Head, at the old Warner Hollywood lot, now known as The Lot. I can tell you without doubt that our final desk automation would not have survived a single version of the sweeping conform changes we saw on that film, had it not been mixed on an Icon.

This flexibility gave the filmmakers an ability to allow the final mix to profoundly affect the picture cut of the film. Picture changes could be made after a playback on the stage, with shot swaps and moves and all, and the Icon automation could quickly be conformed and smoothed graphically in ProTools. Every delicate fader move crafted over months could be preserved.

All of us who know sound, know how drastically adding sound can affect the pace and tempo of a scene.

The ability for a director to quickly adapt a picture cut to a final mix, continuously and fearlessly, is I believe one of the biggest breakthroughs artistically in the relationship between sound and picture.

Perhaps the biggest advantage is the Icon’s ability to have “Virtual Predubs”, mixes than can be unfolded all the way to a unit level. This means we have individual control of every sound element all the way to the printmaster. Because of this, the process of predubbing is, obviously, very different.

For very elaborate films, we still have a way to go. The sheer horse-power needed for 25 predubs worth of virtual automation to the unit level — with pans, EQs, sends, reverb snapshots and so on — is beyond what ProTools is capable of ….. yet.

(left to right: dialogue-music re-recording mixer Chris Scarabosio, 1st Assistant Sound Editor Joel Dougherty, recordist Jared Marshack, and Supervising Sound Editor Craig Berkey, seated in Audio Head Stage B by a Digidesign Icon mixing console)

But ultimately, the bottom line is not the technology. The tools may be different, but it’s the artist who wields the tool that is the most important piece of the puzzle. The Icon, like any other piece of technology, is nothing more than a tool.

Like life, sound is what you make it.

It was very interesting, thanx a lot!

Interesting.THX.Could you share something about the Final mix and the print master stuff.

Great stuff, Erik!

Almost all of my projects in recent years have been structured as “in the box” premixes, meaning that all or virtually all of the editing and premixing has been done in ProTools, keeping it all virtual. We record predubs only as a delivery requirement, but don’t use the recorded predubs in the final mix. In the final each individual sound is funneled through virtual six channel premixes coming out of ProTools that then go through a DFC. Typically there are two ProTools systems carrying effects, backgrounds, and foley. Often all the effects are on one system, and the backgrounds and foley are on the other system. My personal preference is to not use a ProTools “mixing console” control surface, but I know I’m in the minority. I like to make adjustments within ProTools with a mouse rather than knobs and faders. I do use the knobs and faders on the DFC, but most of the work is being done in ProTools.

We can get away with this approach, given the limited number of sounds ProTools can play at one time, because we are very disciplined about making editorial decisions before the final mix. In other words, we come to the final with fewer sounds than would be typical on a more traditional mix, where it’s assumed lots of alts will be needed. One reason this approach works is that on all these projects we spend a lot of time presenting sounds to the director before the final. That way we are pretty sure we know what’s going to make everybody happy before the final starts.

Best,

Randy

Great comment, Randy! Many thanks for sharing those ideas.

Thanks for the great comment, Randy! That’s a very smart and slick way to approach it. Virtual predubs are the way to go!

Cheers,

Erik

Thank you for this tremendous insight into your approach.

thanks for useful data

and tweiks

Thank you for sharing Eric!

Randy that is a great motivation for all of us who work in the box and as Eric said at the end “it’s just a tool, it’s what you make of it” :)

Great stuff!