Different filmmakers work differently, with unique approaches to the sound design process. For some, there’s intense interest and scrutiny, for others there might not be any interest until the end.

I prefer having an actively engaged filmmaker. It makes it much easier to work together and evolve the track over time to make it right for everyone. It doesn’t matter if I think the sound work is great. It’s not my movie. It’s the filmmaker’s baby. If they haven’t signed off on our sounds, things can get really risky as we approach the dub. There’s nothing worse than spending months recording, designing and working on a sequence, just to have all your sounds dumped on the final mix stage and replaced with crappy AVID “omf” temp effects, simply because those are the sounds they’re used to.

That’s why with inexperienced or reluctant filmmakers, we try to engage and instigate the interactive process early. Sometimes all that’s needed is a little inspiration; doing a 5.1 presentation of a favorite sequence early in the schedule is a good way to get everyone off to a good start.

The central strategy we’ve adopted to work with picture editors and directors is to deliver complete sound effects mixes as early as possible. We do these in ProTools. These FX mixes get integrated into the AVID picture cut and completely replace temp effects. Typically we start with stereo bounces. If there’s a piece that a director or editor doesn’t like, they cut a piece out of our mix in the AVID, and put in a sound they prefer. This then serves as a “note” to us, a marker that we need to reexamine that section and try something different. This way, every turnover of a new version evolves the track. Ideally, the whole sound track gets sussed-out this way before we hit the pre-dub stage.

I think first impressions with a new director is very important. I botched my first meeting with director Alex Proyas on “I, Robot,” keeping my mouth shut about my ideas and making him nervous about what I’d bring to the table. These sort of meetings are an important opportunity to establish lines of communication and start generating concepts. It’s important to listen carefully, take lots of notes, and be prepared with some questions of your own. It’s a chance to present some interesting ideas and pitch them if the situation presents itself. It’s never too early (but often too late) to influence the picture.

I remember the first time meeting the filmmakers of “Kung Fu Panda”. A small room at Dreamworks Animation Studios in Glendale was packed with 10 people I’d never met before, and me. Just getting the names straight at first was hard enough. But what followed was a very intense spotting session of a 7 minute prison escape sequence. Director John Stevenson spent a lot of time talking about concepts: how the depths of the prison were lit blue, and this should reflect the icy cold isolation of the prisoner, which in turn should be reflected in the sound. Co-director Mark Osborne talked a lot about the prisoner Tai Lung’s fighting style. Pages were filled with details like the rhino guards’ armor; iron metal plates, hinged with thick leather and neck chain mail.

This scene alone took us 2 hours to spot, playing for a second or two each time we stopped for another note. I filled my notebook with about 20 pages of single-spaced notes. I remember coming back to chat with my co-supervisor Ethan thinking, “just to spot the entire movie will take us months!”

But things brightened up quickly. The filmmakers absolutely loved our first pass on the sequence, which earned us some trust. We realized that in animation, filmmakers have control of over every tiny little detail from top to bottom. Sometimes they feel negligent, wrongly so, that they’re not delivering us enough notes. But not getting lots of notes can actually be more liberating, freeing us up to follow our instincts. Sometimes it takes a little practice for some directors to be comfortable enough to trust their sound team and relax.

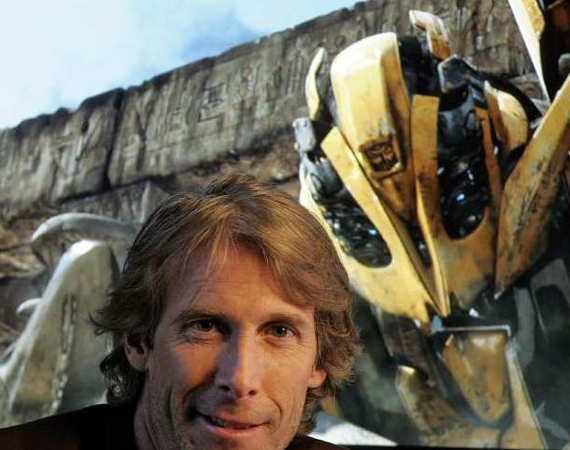

Michael Bay likes having lots of sound work done early. I remember my first week on “Transformers”. Word had come back from picture editorial that Michael was really upset about the lack of sound work done so far for the film. Our response: we weren’t scheduled to start for months!

Well, that changed instantly with a little pressure from Bay’s office, and flash forward a few days and I was working on the first transformation of the movie. It was a Tuesday, and by Friday I had to send the scene to picture editorial at Bay Films in Santa Monica for review. The same thing the following week: I had the week to design a first pass of our autobots for the “Witwicky House” scene, where the robots first show up at Sam’s house. This was a sequence that finally convinced Michael we were on the right track. After that, we could pretty much do whatever we thought was cool, and it would stick.

I think the trick with Michael is to know what you’re doing. He doesn’t have patience for mess ups and won’t tolerate wasting time. Films like “Transformers” are often controlled chaos, or as some of the crew called it: “Bay-os”. How you do can depend on how well you can take the heat.

We continued weekly meetings with Michael through design and editorial, until we started our rolling temp mix in January before the summer release. At this point, we put together a 40 minute presentation for Showest that dovetailed right into premixing and the 4 week final. Michael would come for playback of reels, and to show the movie to executive producer Steven Spielberg. By this point, the film had tested very well with audiences and though we had tons of work remaining, the pressure was off the studio now that they knew they had a hit.

“Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen” had a similar structure to the process, though the schedule was much more compressed due to the writers strike. An impending actors strike threw some big curve balls at the brilliant supervisor Mike Hopkins, compressing the already insanely complicated ADR schedule.

Terrence Malick is also extremely involved with sound. I had the pleasure of working on “The New World” and recently “The Tree of Life”. When we first met to discuss sound, Terry gave us a ranking of what he considered most important:

#1 : Atmospheres

#2 : Sound effects

#3 : Dialogue

#4 : Music

I find the ranking to be fascinating, because it completely bucks convention and is the opposite direction of most filmmakers, who are often too comfortable using clichéd and generic techniques. Using too much music can be a cop out, a cheap filmmaker’s trick that should be moderated. Less music usually makes the music that remains more potent.

I’ve also done sound on a few films for director Bryan Singer. Picture editor and music composer John Ottman is virtually Bryan’s second director, and he worked closely with the sound team. But sometimes Bryan’s aesthetic didn’t always match my own. I remember on “X-Men 2” I had cut a big fight scene between Wolverine and Lady Deathstrike, who both had adamantium skeletons, razor sharp claws, and the ability to heal their wounds. The two characters were stabbing each other violently with their claws. I thought, “how cool would it be to hear the blades hit their metal skeletons as they stabbed?” so I put some vicious grinding blade sounds and lots of sword shings.

Bryan hated it. “What is this? It sounds like a pirate movie!” So we dumped the blade sounds and went in a more punchy direction with the mix.

I remember a similar thing happen in “Superman Returns”. There’s a scene in which Superman goes face to face with a gattling gun, firing a hail storm of bullets. We had the sound of bullets zipping all around us, slicing through the air. Bryan’s first reaction was, “What’s all this zippy stuff?!! Get rid of it!” Turns out Bryan doesn’t like sounds that call too much attention to themselves.

On “Valkyrie”, we hit a little snag with writer/producer Chris McQuarrie during the final mix. We recorded authentic pistols and K98 rifles for a gunfight that takes us to the film’s final execution scene. But Chris got hung up on the “too-clean” fidelity of our sounds, versus the distorted and awful-sounding (but dramatic) production recording cracks. After he had his pass on the guns, I felt upset about the low fidelity of the sounds, and questioned keeping my name on the film. But co-supervisor and re-recording mixer Craig Hennighan, with Ottman’s help, slowly brought our material back in and got a more elegant balance between the production cracks and our FX. My name is still on the movie.

Written by Erik Aadahl for Designing Sound.

thanks a lot, that was great. the last passage reminds me of a job some weeks ago.

I have a lot of respect for the transparency and honesty in this writeup. It takes guts and speaks to ultimate confidence. Very insightful and informative. Nice work.