Another great work of Rob Bridgett:

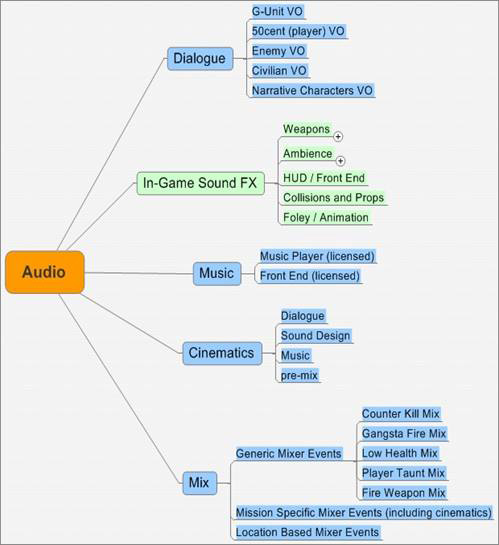

This was the first experience for me as an audio director dropped into a project as it hit production, so many of the things that are so important to game development like getting to know the team and understanding the project both from a detailed implementation perspective and simultaneously a high-level had to happen very quickly. Joining an already existent sound team can be quite daunting, so this feature goes some way into describing the process by which the work was broken up for the team into sensible areas. Again, these are areas I’ve never seen discussed or written about anywhere else so there is always a need to create these articles where there is a paucity of information. BotS was also my first experience of audio direction from a remote location, in that after six months on the ground with the developer in the UK, I returned to Vancouver and was able to finish the game from there. The move back was very handy as the majority of work I was responsible for; dialogue, cinematics and music were all areas for which we had a team on the west coast. Many of the features from the Scarface game were adapted for this game too, such as the taunt button and the custom play-list music player, both making perfect sense for this IP.

Early Production

It became very clear that the production needed a narrative direction as soon as possible, as production was already underway on in-game assets prior to the existence of any written story. We brought in a local writer, Adam Hamdy, to begin to flesh out some very high-level story ideas and get an idea of characters in the absence of an official writer.

These initial ideas and characters were subsequently handed over to the chief writer who was hired in LA, Kamran Pasha, who worked closely with the core IP group (myself, art director, exec producer and lead designer) in Birmingham via several weeks of conference calls.

Together we sketched out the story and characters that were to populate the final game, while all the time working within the constraints of our in-game locations (which were fixed due to the amount of art and level design that had been already produced).

The grand-concept and art direction for the game established by executive producer Julian Widdows and art director Michel Bowes was that of an over-the-top “music video” and arcade-driven in style.

It is always great, as a sound director, to have such a clear brief and this bold visual statement had distinctive inspiration for much of the sound design, especially of the HUD (points accumulation and call-outs), as well as the weapons and explosion sounds being greatly exaggerated and over-the-top.

The game’s overall direction was also not to take the subject matter too seriously, and to have more fun with the license in order to get away from hip-hop — which is all too often is unable to make fun of itself. The dialogue, particularly the inclusion of a taunt button, was designed to fit this brief, and to create a feeling of an over-the-top hip-hop arcade experience. It also introduced a lot of fun and humor into the gameplay — an ingredient often sorely missing from other hip-hop licenses.

Dialogue

Design of a suitable dialogue system with gratifying yet simple interactions was worked on primarily with the design and AI teams. This work began with breaking down enemy reactions and outbursts into AI categories such as “taking cover” / “throw grenade” / “attack” / “covering fire”, etc.

We also broke down all the categories of dialogue that the player character (either 50 Cent or a G-Unit member) would require, in total each had around 50 categories. Each of these categories was analyzed for repetition in actual game play, and corresponding numbers of variants were mapped out for the more common categories, the biggest being the player’s taunts.

The taunt button was going to be central to getting the feel of “being 50 Cent”. Being able to use comical profanity at any time, totally at the user’s discretion, certainly upped the fun factor, and was a technique that I had used previously on the Scarface game.

Also key to getting the taunt button integrated into gameplay and away from simply being a swearing button meant that when used at certain times after certain kills, as part of a combo, it allowed points to be multiplied with timed use of a taunt. The dialogue content of the taunt button was also made upgradable via the unlocking of extra themed taunt “packs” which increase the amount of things that the character can say on the button as the game progresses.

Because the game was set in a fictional Baltic / Mediterranean war zone, we wanted vaguely authentic and indeterminate foreign voice assets to be shouted in original dialects — not in English with a foreign accent, which can often be repetitive and irritating.

This also meant that we could get away with much less offensive dialogue content, because once it was translated and shouted in an angry over the top performance by the actor, it sounded a lot more aggressive than it actually was. Myself and the core IP group all settled on a mixture of Russian, Serbian, and Croatian voices to obfuscate any idea of a middle-eastern location and to deepen the idea of foreign fighters and unknown forces with which 50 Cent and crew find themselves in confrontation.

Visual Style and Sound Design

There is a striking richness and hi-resolution detail to the art direction of the game that initially surprised me when I first saw it. Finely detailed, high-definition particle effects gave clues to the appropriate audio direction for the sound effects in the game. There needed to be a lot of corresponding detail and richness in the sounds that were created for the game, namely in the destruction, bullet ricochets and key explosions.

Adding many layers of rubble and fine debris to the tails of the effects to reflect and underpin the visual density of the game was one of the key directions established for the sound effects design. Another key direction was for the sounds of the weapons that 50 Cent uses in the game. These needed to follow not a realistic weapon model, but one of over-the-top cinematic power.

One of the things learned from the weapons work on the Scarface game was that it is not about having a wholly authentic weapon sound or weapon recordings, but that the feeling of shooting a weapon (something we did at a shooting range in the Nevada Desert for Scarface) that was the key to giving the players the fun and impression of overwhelming power that comes from holding and firing an automatic weapon.

In this sense we chose to concentrate very hard on getting all the various weapons in the game scaled correctly and feeling lethal and fun, which meant that no original recordings needed to be made. We instead concentrated on layer upon layer of creative sound design using only content from Vivendi’s sound effects library.

This over-the-top direction in turn creates an important point-of-view effect for the player, in that they are hearing the weapon from 50 Cent’s perspective and getting his larger than life bulletproof personality communicated through those sounds.

To achieve this, sound designer Mark Willott and I worked very closely on these particular aspects of the sound design, focusing on and fetishizing many of the reload, shell-casing, and bolt-action sounds to augment the firing sounds. In the end we achieved fairly quick cyclical iteration on the explosions, weapons and ricochet sounds, reviewing weekly during production, and these sounds turned out to be crucial to the overall action of the game.

We often found ourselves laughing out loud at some of the gunplay in Blood on the Sand due to its sheer over-the-top nature, which to me is always a great indicator of a solid, fun action game.

With the sound direction firmly established on-site at Swordfish in Birmingham and the focus of production moving onto assets generated in LA, in November 2007 I returned to Vancouver, continuing sound direction duties on 50 Cent remotely via regular conference calls. As I was now responsible for the dialogue and music content in the game, it made sense that I was closer to the center of operations at Vivendi LA in order to work on the same time zone with the executive producers and our LA-based voice-over studio.

It also transpired that the cinematic cut-scenes for the game, on which I was responsible for cutting sound and mixing, were being outsourced to FX-house Rainmaker in Vancouver, and again being on site in Vancouver allowed me a close working relationship with the cinematics team.

Cinematic Cut-Scenes

The cutscenes in development at Rainmaker were delivered on the production Alpha date, giving me two weeks to complete the primary pass of sound effects cutting and pre-mixing for our Sound Alpha date. The cinematics were are all pre-rendered FMVs, and because the in-game characters, sets and effects are all of such high resolution, it is often hard to tell the difference between in-game and cut-scenes.

Due to the high quality rendering of these scenes, there was great incentive to get them to sound as cinematic as possible. A week of Foley recording was carried out at Sharpe Sound in Vancouver, and these Foley tracks were integrated directly into my Nuendo sessions back in the mix studio at Radical.

Working on FMV cinematic visual assets offers much more creative inspiration for the soundtrack than NIS in-game cut scenes in games, as the latter tend to give very low resolution, grey-blocked assets to the sound designers to work on.

The more detail that is visible in the final movies that go out to places like Foley outsourcing, the better the quality of work you get back in the end, due mainly to it being obvious what materials the characters are walking on and interacting with. As well as this, having all the visual and particle effects as part of the movies adds additional clues for the sound designer.

Music and dialogue assets were edited and mastered at Radical by our senior studio engineer Lin Gardiner, ensuring that all the levels of both the score and the licensed tracks from various sources all had consistent volume levels.

Right from day one of my involvement in the project, I wanted to repeat the success we had with the Scarface game in terms of post production time allotted after Beta so we could take time to polish and finesse the game’s sound with everything in place. Sound Alpha and Sound Beta dates were established with the project managers to occur two weeks after both production Alpha and Beta.

It was also always the plan to use the newly constructed 7.1 post-production mix suite at Radical Entertainment, which had recently been set up and calibrated by THX, as the ideal location for the final mix of the 50 Cent game, taking full advantage of the inter-studio sharing between Vivendi studios.

The studio had been designed from the ground up to not only handle the mix of internal projects at Radical, but also to accommodate private VPN based projects from other studios. Audio Lead Mark Willott flew out from Birmingham to Vancouver to join me for the final two week post-production audio phase on the project during August of 2008.

The post-production plan that we followed allowed for a week of sound effects replacement, during which we played through the entire game, flagged priority sound effects that we felt could be improved and used Radical’s in-house sound designer, Cory Hawthorne, to re-work any sounds that we needed to replace.

After a week of sound replacement, we moved on to a week of mixing for the Xbox 360. One of the unique aspects of mixing video games is that, as there are no standards in place for reference level mixing and monitoring, as there are in movie post production, most of the competitive games are of dramatically varying output levels.

It was decided that we wanted to mimic the output levels that Gears of War had used, as this was the game we had been most closely modeling in terms of gameplay and target audience.

To this end we attempted to get our output levels as close to Gears of War as possible, listening at slightly underneath the -79dB reference level as we mixed and referencing the output surround waveforms generated by the game, generally this is somewhat quieter than we would prefer to mix a game, but it matched the expectations of the audience for this kind of game.

As well as matching cinematic levels with those of in-game sounds, much of the actual in-game interactive mixing involved ducking out explosions, ambience, music and physics sounds whenever important dialogue was installed. This was achieved via the installation of mixer snapshots that are triggered to coincide with the event in the game, and then un-installed on event completion.

After playing through and mixing the entire game in surround, final checking of the stereo and mono down-mix was achieved using the Studio Technologies Model 79 monitor controller built into the mix studio’s console desk.

Finally, after mixing the Xbox we cloned all the mix settings for the PS3 version of the game and tweaked a few levels for the discreet PCM 7.1 mix output. The game had been running in 7.1 all through development on the PC, so there was very little extra work to do in order to support the two extra channels required for the PS3.

Missed Opportunities

There are always sacrifices to be made as production deadlines loom closer, and there were a few features and areas of content that we could have improved given more time.

We did plan to record a significant amount of new and replacement revision lines for the game with 50 Cent and the G-Unit. We managed to get these pickups recorded with all of our actors except the G-Unit in the end, purely due to scheduling conflicts and requirements which meant that we needed to cut off our content implementation before we could get any of the new assets.

This is one of the areas that we all felt the quality of the game’s dialogue assets could have been improved, offering tighter integration with the events of the level designers. In the end, what is in the game could certainly have been improved, but is still of high enough quality that we were happy we could complete development on the title.

In terms of music, some of the features were very late at going into our code. Beat-mapping that would allow us to transition the Swizz Beatz score on the exact beat was very late going into the game, but an essential feature that needed to go in.

One feature that we did have to drop was random selection of parts within a looping track which we had to forgo due to the risks involved with introducing new FMOD code updates into our Alpha build.

As such, it was designated as something that we didn’t need to have in order to ship the game, and so rather than have randomly looping parts with each track, we simply had a single .wav track made up of the four previous random parts.

Given these slight improvements and missed opportunities, the whole audio team is very happy with the final game we shipped, especially given the pressure to deliver quality in a high-profile license IP such as this. I’d like to extend my personal thanks and congratulations to everyone in Birmingham, LA and Vancouver who worked on the audio and helped to create a great sounding hip-hop game.

Cory would create several versions of each new sound, each with an identical memory footprint to the sound that was being replaced, and we would then try it out in the game. More often than not we would decide on one of those replacements there and then to be the new sound.

Cinematic Cut-Scenes

The cutscenes in development at Rainmaker were delivered on the production Alpha date, giving me two weeks to complete the primary pass of sound effects cutting and pre-mixing for our Sound Alpha date. The cinematics were are all pre-rendered FMVs, and because the in-game characters, sets and effects are all of such high resolution, it is often hard to tell the difference between in-game and cut-scenes.

Due to the high quality rendering of these scenes, there was great incentive to get them to sound as cinematic as possible. A week of Foley recording was carried out at Sharpe Sound in Vancouver, and these Foley tracks were integrated directly into my Nuendo sessions back in the mix studio at Radical.

Working on FMV cinematic visual assets offers much more creative inspiration for the soundtrack than NIS in-game cut scenes in games, as the latter tend to give very low resolution, grey-blocked assets to the sound designers to work on.

The more detail that is visible in the final movies that go out to places like Foley outsourcing, the better the quality of work you get back in the end, due mainly to it being obvious what materials the characters are walking on and interacting with. As well as this, having all the visual and particle effects as part of the movies adds additional clues for the sound designer.

Post-Production and Final Mix

Music and dialogue assets were edited and mastered at Radical by our senior studio engineer Lin Gardiner, ensuring that all the levels of both the score and the licensed tracks from various sources all had consistent volume levels.

Right from day one of my involvement in the project, I wanted to repeat the success we had with the Scarface game in terms of post production time allotted after Beta so we could take time to polish and finesse the game’s sound with everything in place. Sound Alpha and Sound Beta dates were established with the project managers to occur two weeks after both production Alpha and Beta.

It was also always the plan to use the newly constructed 7.1 post-production mix suite at Radical Entertainment, which had recently been set up and calibrated by THX, as the ideal location for the final mix of the 50 Cent game, taking full advantage of the inter-studio sharing between Vivendi studios.

The studio had been designed from the ground up to not only handle the mix of internal projects at Radical, but also to accommodate private VPN based projects from other studios. Audio Lead Mark Willott flew out from Birmingham to Vancouver to join me for the final two week post-production audio phase on the project during August of 2008.

The post-production plan that we followed allowed for a week of sound effects replacement, during which we played through the entire game, flagged priority sound effects that we felt could be improved and used Radical’s in-house sound designer, Cory Hawthorne, to re-work any sounds that we needed to replace.

Cory would create several versions of each new sound, each with an identical memory footprint to the sound that was being replaced, and we would then try it out in the game. More often than not we would decide on one of those replacements there and then to be the new sound.