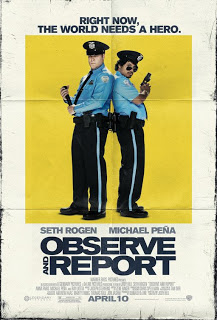

Giving audiences a peek at the day-to-day of Mall Cop Ronnie Barnhardt, “Observe and Report” opened in theaters April 10th. Sound supervisor and re-recording mixer Terry Rodman brought along re-recording mixer Steve Pederson for an old-fashioned mixing stake out on dub 12 at the WB lot. The newly redesigned stage is put through a “normal morning” of prep, HERE. Production sound for the film was handled by mixer Christof Gebert which was primarily shot at Albuquerque’s lovely Winrock Mall. Loyal to the crew of his first film “Foot Fist Way” and HBO’s comedy series “Eastbound and Down”, Jody Hill tapped musician and friend Joseph Stephens to write the score. The rock oriented soundtrack was recorded at Fidelitorium Recordings in Kernersville, NC.

I wanted to thank Composer Joseph Stephens for taking time out to do the following Q and A.

DS: Director Jody Hill talked about particular 1970’s films (“Taxi Driver” and “Shampoo”) influencing “Observe and Report;” Did they influence the score too?

JS: No. “Taxi Driver” music was never referenced…or any other film for that matter. Our score is very loud, very in your face. Ronnie, the main character, has a lot of pent up aggression and we wanted the music to be a bit of a window into that side of his personality; an aggressive foreshadowing, a turbulent insight into his internal struggles which is sort of the antithesis of “Taxi Driver”, which, musically, is very brooding, understated, and repetitive. Where “Taxi Driver” went for the narcotic lull of New York jazz, we went for the pounding drums, walls of feedback, and razor fuzz of punk and rock n’ roll.

DS: How did you discuss music with Jody? Did you converse in musical language?

JS: Jody Hill and I talked a lot about the music while the film was still shooting. Conceptually, we had a strong idea of where the score was going from a very early stage. While I don’t think either one of us really spoke in musical language, we did have a clear understanding about each others musical ideas and tastes. When I described an abstract wall of interlocking, subverted guitars playing only feedback for Ronnie’s arrest scene, he got the picture, just as his description of “The Kiss” (dictating hope; describing that ray of sunshine, that perfect moment which suspends and changes everything and doesn’t seem to want to end) was succinct and very direct. The language of music is pretty universal and has no set guidelines when you know what you like and don’t like and you can communicate your ideas clearly.

DS: How hard was it to develop a theme for Ronnie? How did it have to change over the course of the film?

JS: Ronnie’s main theme occurs at two distinct points in the film. Both points center around his honesty and innocence. The first is at a psychological interview. He tells about his dream of becoming a cop. We wanted the scene to sound sweet and honest and we wanted the audience to get on board with Ronnie’s perception of his place in the world, despite what a sociopath he sounds like in reality. The second time we hear this theme is when Ronnie goes to the police station for his first day on the job. The same theme has an uplifting, driving, and “things are finally changing for the better” feel. Here we need the audience to, once again, get behind Ronnie and pull for him. He seems so happy and proud of himself in both scenes.

It actually wasn’t that hard to develop. The “First Day on the Job” cue was one of the first pieces written for the film. It was actually submitted as a temp idea with the vocal melody as a place holder for another instrument to be added later. However, the vocal had a certain feel and hook that paved the way for many of the other cues and ultimately lead to the overall feel of the score, (that feel being very melodically vocally driven). We wanted to explore that same Ronnie melody at different points with the psych interview being a logical place to revisit.

DS: With “Observe and Report” using a lot commercial songs, how hard was it to make your cues blend in?

JS: Not that hard. This score sounds like it was performed by a band. I used instruments that are traditionally found in rock n’ roll music; guitar, vocals, drums, bass, keys, etc. Much of the score was recorded and mixed at Mitch Easter’s studio, Fidelitorium, which is primarily known for recording bands, not film scores.

There are also a couple “fake songs” in the film; Songs that I wrote and performed exclusively for the film but are meant to sound like pre-existing material from some other artist who licensed the music for use in the film in the same manner that Patto, The Yardbirds, and The Band licensed their music.

There is also the cover of the song “Where Is My Mind?” which was performed by one of my bands; City Wolf. As well, as the end credit song “Babyteeth” by my main band Pyramid.

With me singing “fake songs”, cover songs, and an original song; using the same drummer, recorded at the same studio as the score, it was easy to blend into the other licensed commercial songs throughout the film.

DS: Did this film have a temp score and if so how did that affect the composition process?

JS: We did use temp score here and there. When

I saw the first cut I knew I had to get in there fast because they were editing to temp, interchanging temp, becoming attached to temp, etc. I must say that I’m not a fan of “temp love.” Some of the temp worked really well but some didn’t. After I saw the cut I insisted I get a copy and get to work. The director and editor are close friends of mine so I got involved much earlier than traditional composers. Also, this being my first job with a major studio, I wanted as much time as I could get to work on this. I got home and started sending two or three cues a day, basically facilitating my own temp score. I threw as many ideas at them as I could; trying to get the temp out of picture so they would start editing to my music and become attached to original score. The temp that did remain served as a guideline. I didn’t particularly like following these guidelines but when the temp is working well it can be very useful…and sometimes hard to fight.

DS: Having also composed for HBO’s “Eastbound and Down”, in what ways did your approach to writing differ covering a feature verses a 30min episode?

JS: We were on a tighter deadline with television. There were six episodes that each had different time frames. So I moved much faster. I recorded everything for “Eastbound and Down” from my home – strictly “out of the box.” The instrumentation was different. I used mandolin, accordion, lots of synths, and female vocals. There was also a significantly smaller budget so renting a professional studio was not economical. Granted the cues were less grandiose so a studio wasn’t really needed but this certainly affected my approach. I had to pay closer attention to my mixes because I didn’t have a sound engineer or $15,000 monitors to fall back on.

In terms of difference in approach, the “Observe and Report” score was very guttural and raw; Lots of vocal passes and loud guitars, the writing was very traditional and basic, and at times more loose in large part because the score has that rock n’ roll feel. There were a lot of happy accidents. The pulse and instrumentation is very familiar and accessible. I think that comes somewhat naturally to me. Same with the TV show, though with “Eastbound and Down” the music went with jokes a little more, although some were quite serious in tone. “EB&D” cues were also shorter.

There were a couple cues on “O&R” that were massive. One had something like 150 drum tracks. Also some cues took a few passes before we got it right. With “O&R” I worked hand in hand with a music editor who helped tremendously in keeping me up to date as the picture cut changed and editing cues as needed. I couldn’t have done it without him. I did not work as closely with the music editor on “EB&D” though she was also great.

DS: How does composing music for a film differ from writing music for a band? What do you like more?

JS: The ultimate difference is that writing music for a band is essentially writing music for you. You are your own judge. What works and what doesn’t is not up to anyone other than you. When you’re happy; when you can say “This song sounds perfect to me”…that’s it. You’re done…next song. Certainly you want to push yourself and strive for excellence, but other than band mates, you don’t have that many people looking over your shoulder or waiting, sometimes impatiently, for the product. With film scoring, everything passes through a variety of stages of approval. It’s sort of like putting the music under a microscope. “The director loves it but the producer doesn’t think it works.” It gets a bit dissected and whittled down…in a good way. When you’re scoring something, you’re making music for someone and something else so you can’t cling to things. It’s all subject to the approval of others. You have to work together and you have to roll with the punches.

There’s also the obvious difference of using pictures. Scoring works in tandem with action on screen, dialogue, editing, sound effects, etc. In many ways, these elements do a lot of thinking and decision making for you. Cues have to be of certain length and tone. It has to interplay with a lot of factors that are out of your control. You have to listen for room to move and watch for interference.

I haven’t worked enough as a composer to know whether I like it more than writing music for myself. Composing can be very stressful, but it has big rewards. There is truly nothing like hearing your music up on the big screen. It’s very unique. However, writing for a band comes from and is channeled back directly into your heart so it’s hard to compete with that. I’m very lucky to be in the position to do both.