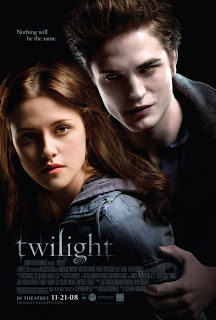

“Twilght” descended into theaters November 21st, luring millions of tweens and this blogger, (only for this post, I swear!) to multiplexes. Supervising sound editor Frank Gaeta clocked time in editorial as well as the dub stages at Wildfire Studios alongside fellow re-recording mixers Marshall Garlington and Leslie Shatz. While Gaeta continued his working relationship with Catherine Hardwicke, “Twilight” marks production sound mixer Glenn Micallef and composer Carter Burwell’s first gig with the director. Music tracking took place at Air Lyndhurst Studios in London with Burwell at the helm.

“Twilght” descended into theaters November 21st, luring millions of tweens and this blogger, (only for this post, I swear!) to multiplexes. Supervising sound editor Frank Gaeta clocked time in editorial as well as the dub stages at Wildfire Studios alongside fellow re-recording mixers Marshall Garlington and Leslie Shatz. While Gaeta continued his working relationship with Catherine Hardwicke, “Twilight” marks production sound mixer Glenn Micallef and composer Carter Burwell’s first gig with the director. Music tracking took place at Air Lyndhurst Studios in London with Burwell at the helm.

A more consistent blogger than I, Carter documents a ton of his work, HERE and was kind enough to log a little Q and A time for us.

DS: How was “Edward’s” on screen piano playing handled from a score point of view? How is on screen performance normally approached? Have you ever had to compose for an actor just performing gibberish with an instrument?

CB: They shot Edward playing before I was working on the picture, and the actor, Rob Pattinson just improvised (he’s a musician, fortunately). I think Rob hoped they’d keep his version, but it seemed clear that the final music should be thematic to the film. I tried to write something that wouldn’t be obviously wrong for his fingering, but it wasn’t perfect. The director wanted to re-shoot the scene so that he could play along to the final music, and ultimately the studio paid for this. (You may want to read the whole story on my web page, HERE.)

DS: Why did you decide to feature the guitar and piano so prominently in the “Twilight” score? In the composition process, how is the decision to feature any instrument over another reached?

CB: The Edward character plays piano in the book “Twilight”, so it was always going to be important, and I settled on that as a solo instrument in the Love theme. The steel-string guitar was used for its fragility and warmth, which seemed appropriate at the start of the relationship between the lead characters. Later in the relationship, nylon string guitar is used for its more subdued, rounder quality.

DS: In a tailored-for-teens movie like “Twilight” where popular licensed music is an important factor, do you find it hard to get enough screen time for your musical point of view?

CB: It wasn’t a problem in this film, but sometimes it certainly is. In this case, the director wanted score for most of the key scenes, and there were no places where songs pushed out score.

DS: As a composer, do you battle with temp love (something we in the Sound Editorial department deal with constantly)? Do you ever have to mimic other scores because filmmakers are too fond of the music in the AVID tracks?

CB: I do battle with temp love all the time, unless I can convince the director not to use temp. In the case of “Twilight” I started giving the director synth sketches early in the hope that they could replace the temp, but she worried so much about whether the executives would understand the sketches that she didn’t use them until so late in the game that new problems were created (see my web page for the Love Theme problem). Generally I refuse to do the “mimic” thing, and I’d rather they just license the temp if they love it. Sometimes they do (as in “Three Kings”) but mostly they don’t.

DS: How do the Coen brothers approach the score in their films? What is it like working with filmmakers with whom you have a two decade long relationship?

CB: There’s no easy answer to this question. The working relationship is, of course, simplified because we have a working language. Still, every film is different and it’s just as difficult to find the musical answers with their films as with any other.