DS: What are some of the airplanes that you’ve recorded?

JA: Mostly World War II planes, and that usually happens two ways. Either I go to an air show and record them as best as conditions will permit. On other occasions I would just call the owner of a plane. Like Lefty Gardner, he had this beautiful twin engine  P-38. He regularly performed at air shows. The Nazis called it the “Forked Tail Devil”. I said “I’d like to record you, I’m going to make a CD about your airplane’s sounds and I want to interview you.” I’d like to come down to your ranch in South Texas. Bingo! I also was prepared to pay. Sometimes this was free. Other times it would be a couple of thousand dollars. These recordings came out the best usually. Paying gave me a certain amount of control and told the owner that I was serious.

P-38. He regularly performed at air shows. The Nazis called it the “Forked Tail Devil”. I said “I’d like to record you, I’m going to make a CD about your airplane’s sounds and I want to interview you.” I’d like to come down to your ranch in South Texas. Bingo! I also was prepared to pay. Sometimes this was free. Other times it would be a couple of thousand dollars. These recordings came out the best usually. Paying gave me a certain amount of control and told the owner that I was serious.

I also traveled to the UK and recorded the only flying German Messerschmitt Bf-109 with a genuine Daimler Benz DB-605 engine. This was the real deal. For this trip, friends offered to lend me some money to do the trip. It was awesome. I also arranged to record an interview with a German WW2 Ace, General Gunther Rall on this trip.

On another trip I was able to record an entire collection of flying WW1 planes while my friend photographed the collection. This was in perfect conditions; a private ranch in Paso Robles where the owner had built an Aerodrome on top of a mesa. There was not even a light breeze at 8:00 am when they flew the planes.

These WW1 planes were designed and built in the mid teens. The entire aircraft was far back on the aircraft evolutionary line. For cooling purposes the designers made the whole engine rotate with the propeller connected to the front of the rotating engine. The crank shaft is attached to the body of the plane, so the crank shaft doesn’t move, the finned engine spins in space. And it must weigh hundreds of pounds. Can you imagine that spinning cast iron thing, with a propeller on it, in front of the airplane? If you changed direction it was like a gyroscope. It fought you. It didn’t have a throttle in the conventional sense either. The only way they could control the speed of the engine was with a “blip switch” to cut the ignition and spark to individual cylinders. So the engines had 9 cylinders on it, and at full speed it was 9 cylinders firing, and it sounded like a lawnmower eerrrhhhhhhh, you know. And if you wanted it to go slower, you would move a little lever back that said 9,7,5,3,etc. so it would be running on fewer and fewer cylinders, and it sounded sort of like a corn popper. They flew these planes and it was just gorgeous. Other ones, they had so many wires and cables on them, holding the wing and everything together, in addition to the engine sound it would be just a rush of wind through the wires and cables. Really really cool combination of these two particular airplanes.

Sometimes it was a matter of being brazenly polite. During the period when I was recording Lefty Gardners P-38, he was performing at an air show in Fresno. I said Lefty, “I’d like to record your aerobatic routine during your performance up close and personal”. “I’d like to get right near the runway while you’re doing your performance”. That meant he would be doing the maneuvers right over my head. I said “I want to be on the taxi way, right next to the runway, and I have to be able to drive out there.” We had a 1980 VW camper at the time. So I said “I want to park out there while you do your performance”. It was loose enough in those days that he was able to go to the directors of the air show and say “I’ve got a friend of mine who’s doing a record or CD about me, and he said he’d like to park right on the runway while I’m doing my performance”. Well they let me do it.

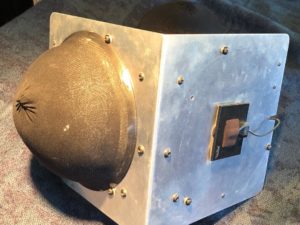

Jeez, so there I am parked in the van right out on the edge of the runway. I slid the door open on the van and placed the microphones on the side windows about 4 feet apart. By then I had discovered PZMs. They had a real natural sound to the point where if I moved away from them, and a fly or a bee landed on the microphone, I’d slap the side of my head, it sounded so natural. It just sounded like I didn’t have headphones on. It was just like real life, and that’s what was coming out of the microphone. So this I really liked. So I taped the PZMs to the side window glass of the van, and covered the mics with large kitchen strainers and that kept the wind from messing up the recording. I was very quiet in the van with my battery operated Sony PCM F1. During the 2 days of the show I got over a half hour of gorgeous P-38 sounds. It doesn’t always come out like that, but sometimes it does.

Jeez, so there I am parked in the van right out on the edge of the runway. I slid the door open on the van and placed the microphones on the side windows about 4 feet apart. By then I had discovered PZMs. They had a real natural sound to the point where if I moved away from them, and a fly or a bee landed on the microphone, I’d slap the side of my head, it sounded so natural. It just sounded like I didn’t have headphones on. It was just like real life, and that’s what was coming out of the microphone. So this I really liked. So I taped the PZMs to the side window glass of the van, and covered the mics with large kitchen strainers and that kept the wind from messing up the recording. I was very quiet in the van with my battery operated Sony PCM F1. During the 2 days of the show I got over a half hour of gorgeous P-38 sounds. It doesn’t always come out like that, but sometimes it does.

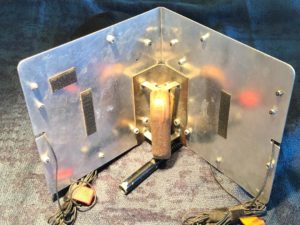

DS: Can you explain what these are?

JA: They’re metal kitchen strainers with stockings on them. They covered up a pair of PZM microphones velcroed to a 20” by 10” flat aluminum panel folded in the middle so that there were (2) 10” by 10” square metal panels at 90 degrees to each other. They had a metal handle that I made to hold them. They worked well. I could even stand in prop wash without wind buffeting. Later I started using a Crown version of my system (holds up Crown SASS-P MK II). This is what I eventually started using, and the idea of course is that the microphones are about as far apart as your ears are on your head. It also has a protuberance that sticks out like your face does relative to your ears. It’s not as dense and heavy as your head but it worked wonderfully for me with what I wanted to do. It makes really natural sounding recordings, rather than a single point, or a spaced pair. These are actually PZM microphones in there. After I went from a single point, that’s what I started using. And I tried all different kinds of mics, such as a pair of Schoeps boundry mics and B&H omni mics on stands. In the end the SASS-P worked the best.

JA: They’re metal kitchen strainers with stockings on them. They covered up a pair of PZM microphones velcroed to a 20” by 10” flat aluminum panel folded in the middle so that there were (2) 10” by 10” square metal panels at 90 degrees to each other. They had a metal handle that I made to hold them. They worked well. I could even stand in prop wash without wind buffeting. Later I started using a Crown version of my system (holds up Crown SASS-P MK II). This is what I eventually started using, and the idea of course is that the microphones are about as far apart as your ears are on your head. It also has a protuberance that sticks out like your face does relative to your ears. It’s not as dense and heavy as your head but it worked wonderfully for me with what I wanted to do. It makes really natural sounding recordings, rather than a single point, or a spaced pair. These are actually PZM microphones in there. After I went from a single point, that’s what I started using. And I tried all different kinds of mics, such as a pair of Schoeps boundry mics and B&H omni mics on stands. In the end the SASS-P worked the best.

So the planes, a whole raft of WW2 fighter planes…P-51 Mustangs, Bearcats…sometimes someone wanted me to record it because they were doing a video, so I got in the back seat and recorded audio. One of my favorite ones was a Lockheed Electra, which is similar the kind of airplane that Amelia Earhart flew and died in. Jeez, that’s one of the most beautiful recordings that I have ever done. I was in the front seat on the right hand side, only a couple of feet from the right engine and propeller.

So the planes, a whole raft of WW2 fighter planes…P-51 Mustangs, Bearcats…sometimes someone wanted me to record it because they were doing a video, so I got in the back seat and recorded audio. One of my favorite ones was a Lockheed Electra, which is similar the kind of airplane that Amelia Earhart flew and died in. Jeez, that’s one of the most beautiful recordings that I have ever done. I was in the front seat on the right hand side, only a couple of feet from the right engine and propeller.

I recorded a B-17 bomber from the inside. I stood right behind the pilot and I got the whole start up, the take off. Another recording was inside a Lockheed Constellation. That’s a big beautiful 4 engined propeller driven airliner. It had a beautiful swoopy shape and 3 rudders. It had a haunting sound, 4 very large engines in it, and I got a beautiful startup, take off, and landing, from inside and outside perspectives.

Another big event was around ’93, they had gotten a WWII Messerschmitt German fighter plane fully restored, and they were starting to fly it in air shows and I said jeez, I need to get that. I’d never flown to Europe. I’d never done any serious traveling. I was kind of agoraphobic about flying, and especially flying all the way across the ocean. So I called up the people that had restored it, and I said that I wanted to come over and record it. I had to find out who to call and all that kind of stuff. It was quite an adventure. They told me they would charge me $2,500 to fly the plane for me. So I did that.

Colette and I went over there. They flew the plane slowly by me, in a display mode. People don’t understand sometimes, you know, what you want. I knew what I wanted, but maybe I wasn’t so good at explaining it to them. So this guy is flying the plane like I ask, kind of lazily coming by. I didn’t know how to complain to them then. So I got back home and I took a listen to it, and I said “jeez, I can’t do anything with this”. And I had to figure out how to tell them that I couldn’t do anything with it, because they had contacted me and said “how’s it going with the project?” I said “well, I can’t really use the recording. It doesn’t scare me. This is Germany’s top fighter plane of the second World War. They strafed, and shot up, and killed American pilots. There was an emotion in there, it wasn’t just lazily flying by at 100 MPH or something like that”. Well, that was the perfect thing to say because they said “well, we understand that”. I knew that they flew the plane aggressively on occasion. And I said “I’d like to come over again and I’d like to record it, and I don’t know if I can afford the $2,500 again, so what can we do?”

So they let me come over, and they got a really good aerobatic pilot, one of the other pilots. We came out Easter Monday morning, a holiday in England, and he just ripped the place up. Aerobatics right over my head. It just sounded awesome. It was at full power – all of the really really interesting sounds of that airplane, on display and on tape. It doesn’t sound like any other airplane.

I figured out that I was running out of things to record. One thing about airplanes is there’s millions of airplanes, but there’s not so many different engines. The same engine in different airplanes almost sounds identical. Like a British Spitfire, for instance, has the same kind of engine as a P-51 Mustang. I don’t think anyone can tell the difference if one’s flying by or the other’s flying by. It mattered more what kind of engine it had in it.

DS: Are there any airplanes that you are looking to record in the future?

JA: Yes, sometimes it’s not necessarily the plane, but the circumstances that the plane’s being flown in. I can’t imagine all of those, but I’m running out of them. The other thing is, making a CD and hoping on selling them. Most people know about 3 or 4 or 5 airplanes. B-17, P-51, Thunderbolt, and a few other various WW2 airplanes, so if I come out with a F7F Tigercat, they don’t even know what that is. I liked it, and I thought it was a real interesting CD, but the general public really didn’t know what it was. It boils down to how good it sounds regardless of what kind of airplane it is.

I’ve done a number of airliners, so I got that. I did bombers, and I got those. Those unfortunately cost a lot. If they take that plane up it’s going to cost me thousands of dollars to get a ride in it. So that becomes a limiting factor, unless I can somehow get it free, and I don’t like to do that. One plane that I’d really like to record is a Russian Bear. I don’t know how I’d ever be able to do that. It’s this real strange airplane that the Russians built and still use. There are 4 huge turbo props on it. It looks strange, big 4 engine swept wing bomber. Our B-52 is what counters that. The B-52’s just a jet. But this turbo prop… I’ve seen videos on youtube of it, and it has a nice sound to it. I’d love to record that. There’s a few other engines, a Hawker Typhoon for instance. That is one that had a very elaborate engine that was touchy and had many problems, but when it was working, it was the fastest. The engine was a Napier Sabre with 2000hp and 24 cylinders arranged in an H pattern block, 2 flat 12s on top of each other.

DS: Do you have a favorite airplane recording?

JA: I’d have to say that it was the Messerschmitt Bf-109.

DS: When you first decided to make your aircraft recordings into a record, how did you decide what kind of information you would put on the record?

JA: That’s a great question. Unbeknownst to me, I had discovered what I wanted to put on the record back in the late ‘50s, when I was in high school. I have happy memories of that period of my life. The Indianapolis 500 mile races were broadcast over the radio back then. I used to sneak downstairs to listen over my folks’ Magnavox at around 8:00 am on race day. I loved the sounds and the excitement.

After school I used to hang out at our local record store and browse. There I found on Riverside Records a whole series of Automobile Racing records. One was “Sounds of Sebring” another was “The incredible sounds of the two greatest Grand Prix cars ever built: The W125 and W163, driven in special demonstration at Oulton Park, England”. I played that record over and over. I’m sure I wore it out. You can listen to it in its entirety, right now, complete with ticks and pops, though not very many. Anyway, if you listen to the record you’ll hear the sounds of the cars, the two British drivers being interviewed and Carl Kling of the Mercedes racing team speaking in German about the history of the two racing cars. This was the model I used for my recordings 30 years later.

DS: The topic for the month is inversion. Have you ever recorded an airplane while it was inverted (upside down)? Does the tone or sound of the airplane change when it’s inverted?

JA: This is an interesting question. Let’s think for a minute about the sounds an aircraft makes while moving through the air. There is a relatively large engine, many times it’s over a thousand horsepower. They’re may be multiple engines. There is sound coming out of the engine exhaust pipes. There is the whoosh of air moving over the wings, tail and fuselage. Most importantly, there is the sound of the propeller[s] which can have their tips reach supersonic speeds and break the sound barrier. The relationship between the flying aircraft and you, the recordist, is constantly changing as well. Then there is the relationship between you and the plane, and the plane and the ground, and the plane’s reflections off the ground and buildings and you, which are all constantly changing. What makes recording airplanes so interesting to me is all this movement. If that plane were sitting in front of you, on the ground, with running engines not moving, it would sound similar to a loud car idling.

What makes airplanes sound so great to me is that all this sound is moving through the air. If I’m recording a plane doing aerobatics, it’s constantly moving through the air right side up or inverted or going up or going down, sounding different all the time. I don’t think a plane flying by right side up would sound any different than the same plane flying by inverted.

DS: Tell us a little bit about your techniques. Do you typically record from inside the airplane? Do you record from the ground?

JA: I think the only technique, is avoiding at all costs ruinous noise, including wind, people talking, other airplanes or cars or trucks. I can’t emphasize this enough. If you’re not careful with ambient noise awareness and management, your recording may be unusable. The reason this is so important, is that you will frequently find yourself using expansion and compression techniques, editing, even “gain riding”. When I’m out recording, I can hear people talking or laughing a block away through my mics. I get as far away from that as possible. When I make a recording from within the airplane, I place mics on the inside of the windows, etc. Typically, though, I’m inside the plane with recording gear in my lap. The most important perspective for me though, is the ground perspective, with the plane maneuvering overhead through the air.

DS: Do you put mics on the outside of the airplane?

JA: No, they just get blown out by the wind noise right away.

DS: What type of gear do you use?

JA: I use a Sound Devices recorder with a SASS-P MK II microphone and Sony 7506 headphones.

DS: How do you go about getting ahold of the different airplanes and finding someone to fly them?

JA: Many historic aircraft are owned by museums. In that case I contact the museum. To record at the Reno Air Races, I need to apply for a Press Credential each year, which I have since 1984. Same thing with other air shows. The “Warbird” community is fairly small and many magazines cover the goings on. It’s reasonably easy to make contact with the folks doing interesting projects.

DS: Are you a pilot yourself?

JA: No

DS: Have you ever licensed your recordings for television, film, or games?

JA: I’ve never advertised to the Post Production industry. They’ve contacted me though. Yes, there was The Aviator and a couple of other films, a really good one for the Reno Air Races, Air Racing 3D. I’ve done deals with a number of gaming companies as well. EA, Lucas Arts, and others have licensed my sounds for their games.

DS: Do you plan to release your recordings as sound effects libraries?

JA: Yes, that’s the direction that I’ve been thinking about going. I’d like to make them available on my website in the future. It’s complicated, though.

DS: Do you plan to record any other vehicles besides airplanes?

JA: I really like cars, almost as much as planes. I frequently record them at races. But governing organizations such as NASCAR, NHRA, and CART have all the media locked up. I’ve attempted to work within the rules, but it’s next to impossible.

DS: Any advice for people that are just starting out?

JA: “Do what you love the money will follow”. It’s worked for me very well. Try and eliminate financial success as a criteria for overall success. I wouldn’t trade anything for the people I’ve met and the experiences I’ve had recording airplanes. It’s been the time of my life and I’m still doing it at 76 years old.

Great interview! I loved reading these

Thank you Haydn Payne!