When thinking of voice user interfaces as pure technology, it may not sound appealing to some of us who are in this business for the art. Even when thinking of the technology behind the art, it is comprehensive why some people would shy away from it. What’s compelling about VUIs, however, is not necessarily the ones and zeros that magically enable machines to speak to us; rather, it’s one element that all of us deal with every day: communication.

As sound designers, the single most important aspect of our craft is that of being able to effectively communicate with an audience, be it with dialogue, music or effects. Similarly, the critical outcome of a voice user interface is to clearly communicate with, and understand us.

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence technology has been enabling us to design impressive conversational systems. Take the Google Duplex for example. Announced in May during its I/O conference, Google introduced to the world the astounding interaction between its voice assistant and a real person over the phone.

Looking back at movies that have explored the human-computer relationship, it’s interesting to observe how much speech recognition has evolved to where we are now. However, before diving into the cinematic universe, let’s talk about some key characteristics of VUI design, as well as briefly touch on the following voice-based technologies.

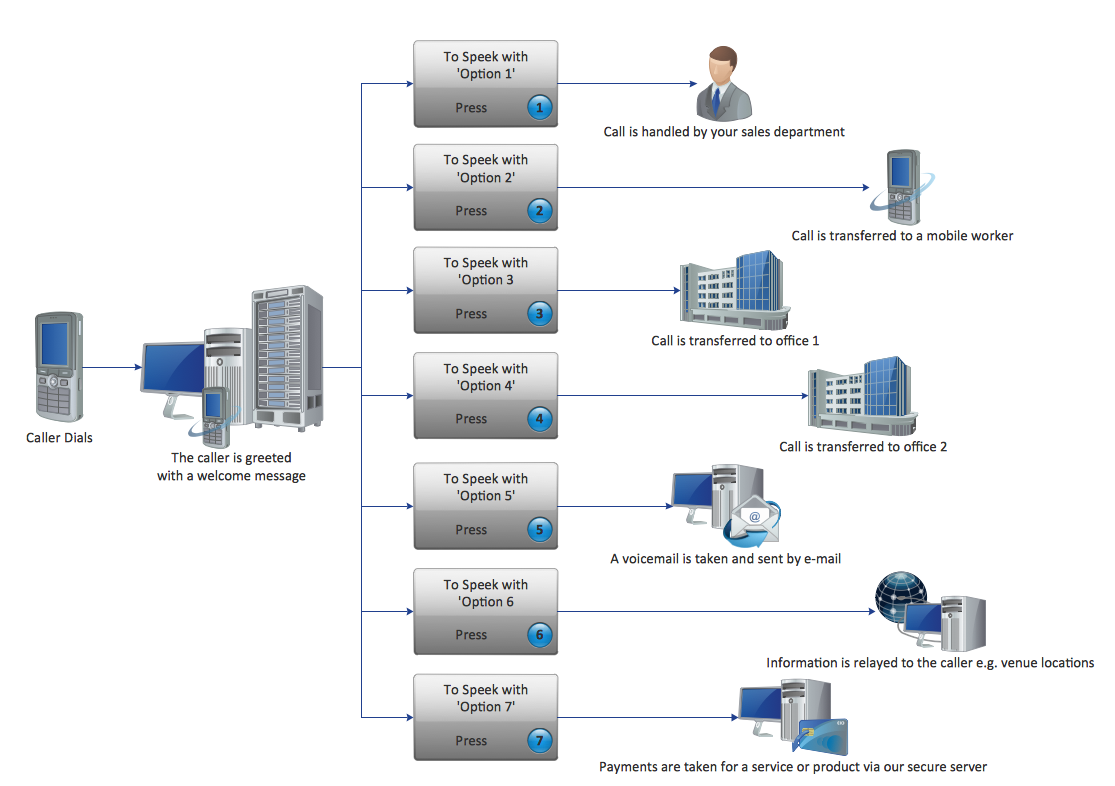

IVR — Interactive Voice Response

On Chapter 1 of her book, Designing Voice User interfaces: Principles of Conversational Experiences, Cathy Pearl introduces the reader to interactive voice response systems, which are designed to recognise speech and carry out tasks. A common use for IVR systems is that of selecting options within a customer-service telephone call, such as internet setup, credit card enquiries or the booking of medical appointments.

Furthermore, interactive voice response are advantageous as they are available 24/7, which means that a customer is able to retrieve information and/or book appointments anytime they need, regardless of the availability of an employee. On the other hand, despite the economical and practical conveniences of IVR systems, its form of communication is not as effective and interactive as that of VUIs. Lack of intelligibility and excessive information are common disadvantages of this model.

TTS — Text-to-Speech

Text-to-Speech systems, also known as Speech Synthesis, are accountable for converting normal language text into speech. As opposed to IVR systems, a person records a broad variety of speech units which are then sorted into linguistics categories, such as phonemes, syllables, phrases and morphemes. Then, a database is created and as soon as person types something, the system will therefore analyse the database, link the units together and transform the given text into speech. The Kindle app, for example, has a built-in TTS system whose quality is quite impressive.

The advantages of TTS lie upon listening to books where and audio version isn’t available, as well as assisting people with dyslexia or other visual impairment, for example. Conversely, as Clifford Nass and Scott Brave describe in their book, Wired for Speech: How Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer Relationship — at Location 249 on Kindle, within the ‘Voices’ section in Chapter 2 –, speech systems tend to have inexplicable pauses, misplaced accents, discontinuities across phonemes and inconsistent structures that make them sound nonhuman.

Voice User Interfaces — Design

The relevance of the aforementioned technologies comes into play when talking about the design of VUIs. The image below displays the myriad of voice assistant devices available today, all of which are competitively responsible for the same action: understanding and communicating with humans effectively.

In order to accomplish such task, designers must work around two critical elements responsible for making VUIs possible: Natural Language Understanding (NLU) and Conversation Design.

A branch of artificial intelligence and computer science, natural language understanding is the technology in charge of analysing patterns within human speech in order to accurately deduce what speakers actually mean. Despite being quite lengthy, this video from Amazon is an excellent source of information about it — and about voice design as a whole. If you prefer to skip to when they enter the ‘Building for Voice with Alexa’ topic, jump to 14:30.

Conversation design, on the other hand, is about the flow of the conversation and its underlying logic, as described by Google on this link. In addition, Cathy Pearl comments on the misunderstanding surrounding conversation design — that people use the term as a means of identifying any time a person interacts with a system by voice or text. Despite not being necessarily wrong, it goes beyond designing but one conversational turn, that is, one interaction between the user and the system. One of the challenges of conversation design is designing a VUI system where the human-computer interaction surpasses one turn; where the system is able to remember information stored in previous turns in order to maintain the flow of the conversation.

– Open the pod bay doors, HAL.

– I’m sorry Sir, I’m afraid I can’t do that.

For many decades, films have been artistically portraying what high fidelity voice user interfaces could do for us. As opposed to struggling to overcome the one-turn conversational barrier most assistants currently have, Stanley Kubrick’s vision of a voice user interface in 2001: A Space Odyssey was one whose vocabulary and fluidity were proficient and flawless, respectively.

By contrast, the Google assistant has been able to remember previous conversational turns for only a couple of years now, despite its limitations. Have a look at the video below for comparison with the HAL 9000.

Along with conversation design, goes the idea of a persona: what establishes a unique characteristic to the VUI. In other words, what makes it sound more similar to a person rather than a computer. The example demonstrated in Google I/O was, at the time of this article, the closest robotic personification of what a human really sounds like — and that leads us to where technology meets art.

Aesthetics if Film

As opposed to the challenges of reality, filmmakers and sound designers have been portraying VUIs in film as HiFi for quite some time now. However, there hasn’t been much change in the aesthetics of computerised voices in recent years. In 1966, two years before 2001: A Space Odyssey was released, speech recognition was popularised by the original Star Trek series. Among all of the following movies, the aesthetics in Star Trek was the only in which a LoFi approach was embodies. In addition, if you listen closely, you can even hear the voice actress breathing in between sentences — perhaps this was a mistake instead of an intentional edit.

When audiences were introduced to 2001: A Space Odyssey, the idea of a modern speech recognition system was one with a fluid and impeccable conversational system. The same aesthetic is found almost 20 years later on the TV series, Knight Rider (1982), as shown on the video below.

In this case, the VUI’s conversation is not only flawless, but the speech transposes the correct vocal intonations when confronted by Michael, played by David Hasselhoff. While it does add up to the story, when reflecting on its overall aesthetic, the voice doesn’t sound as different as that of an actual person speaking over the radio, for example.

Released in 2013, the movie Her, directed by Spike Jonze, introduced us to the ideal VUI stage — one that by just using a tiny ear piece you could speak anything to the VUI as if it were a friend of yours, who knew everything about you. One of the elements that captured my attention in that movie, however, wasn’t the interaction with the advanced operating system, but a speech-to-text interaction in the opening scene. This approach is interesting as it’s not a simple speech-to-text system, but an interaction with a VUI that clearly understands pauses and other speech nuances, as well as instructions.

Last but not the least, within the Marvel Cinematic Universe, we have Jarvis — and Friday — from Iron Man, which you’re all definitely familiar with, as well as Karen (Suit lady), from Spider-Man: Homecoming. I want to draw specific attention to Karen for one particular reason: while it does sound more like a human regardless of the robotic texture, depending on what is asked of her, the tonality of her speech shifts to what a machine sounds like without a persona. Pay close attention to when she says “well, if I were her, I wouldn’t be disappointed at all“. You’ll hear the comforting tonality she expresses, as if she’s literally beside Peter, whispering. A few seconds later, Peter asks how long have they been there, and she replies: 37 minutes. At that moment, the tonality changes to how Siri or Alexa would reply if you asked them to set a timer.

An Idea

If you read up to here you’re probably wondering what’s the relevance of reflecting about VUIs and lower quality speech recognition technologies. Well, this article was not written with the intention of questioning our artistic interpretation of advanced speech systems in film. Rather, the aim is to expand our understanding of voice technologies and how they are designed so that we can explore it in media through art.

I first came across conversation design when researching material for this article. It had never occurred to me the challenges developers face when making a system understand the subtle nuances within human language. Perhaps we, as sounds designers, could take advantage of these obstacles to better design a robotic voice, where the sonic texture is not necessarily the core of the system, but rather how it communicates with a character.

Whether or not breaking the conventional “rules” of how a VUI behaves in film would be effective is entirely subjective to the needs of the story. On the other hand, I would argue that today’s standards of cinematic VUI design could become another cliché as we approach the baseline that sound designers have been suggesting for years. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Think of it as a stimulus to challenge the known and explore the unknown.

Happy creating.