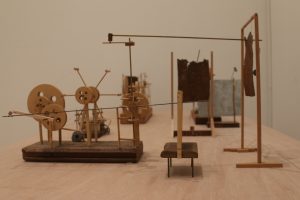

O Grivo is a duo of Brazilian musicians-sound designers formed by Nelson Soares and Marcos Moreira, whose work can be currently seen and heard in the US as a part of the Soundtracks exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco. The duo has a broad palette of activities, ranging from film sound to the visual arts. All the different aspects of their work seem nevertheless to be articulated in a very balanced and simple manner. The relationship, for instance, between what we hear in of their concerts and the physical presence of O Grivo‘s delicate, handmade sound devices make us feel their music as a very concrete, close experience. It is as if we could touch it, walk around it, even ignore it momentarily to pick up its thread later. Their music could perhaps be related to what a zen philosopher would call kono-mama or sono-mana by which “the meaning thus revealed is not something added from the outside. It is in being itself, in becoming itself, in living itself (…) Kono- or sono-mama means the ‘isness’ of a thing. Reality in its isness”

DS- Your scope of work comprises a very broad range of activities. I would like to know how you have developed them in the course of your career and how they relate to one another. Could you talk about how it all started?

Nelson – Sure! The duo started in 1990. I’m a drummer and Marcos used to play the guitar at that time. For our first presentations, we used pre-recorded sounds as well as a form of accompaniment. Gradually, we started building some sonic gadgets but it was all very primitive yet.

DS- Were these gadgets mechanical or electronic at first?

Nelson- Mechanical.

Marcos- Actually, the samples we previously used on stage were made from a handful of ordinary objects. We manipulated those objects and recorded the sound of them. At first, we decided to bring these same objects to the stage and play them live. And, later, we started to create our own devices. At that time, they were very primitive, as Nelson has already said. The motor that made them function was making more noise than the devices themselves!

Nelson- As I remember these machines and objects were huge, they took the whole stage…

DS- And how did you start working with film?

Nelson- The first thing we did was the score for a film by Patrícia Moran called Adeus, América (1996). A little bit after that we started doing a series of concerts as part of a project called Cine-Olho (Kino-Eye, which is also the name of a movement created by the russian director Dziga Vertov in the 1920s). There, we did live music as an accompaniment to silent films, and used conventional musical instruments along some of the first devices created at the time. It was our first experience performing with projected images and the films were spectacular: René Clair, Chaplin… we enjoyed it so much that we keep doing this up to now.

DS- And were these concerts all about improvisation?

Marcos- Not quite. We did some serious research beforehand. There was a bit of improvisation as well, but not very much.

Nelson- It depended on the film actually. For instance, in a film like Anémic Cinéma (Marcel Duchamp), we let things run very loosely. In other films everything was rehearsed and controlled. We started working with Cao Guimarães at that time as well. He made a lot of experimental short-features and we did the sound for those. Soon, we started to project those short films on our presentations as a new element of our work. Forthe concert we recently did at the MOMA, we projected a video made by ourselves: some images of our sound machines, done with a macro lens, showing their details in an almost abstract way. The movement of the machines themselves is what edits the images during our presentations. It’s nothing close to some kind of narrative, but just a simple, direct way to articulate these two elements.

DS- These machines and sound devices play a very important role in your work. How did you get to the point you are now? Why do you think these machines are important?

Marcos- This may sound funny, but it is the truth. As we were only two, it was kind of hard to make more complex orchestrations having only two sound sources. That’s why we started playing with these objects. We wanted to create new possibilities for our work. The samples used at the beginning of our career had that same purpose, but the machines were somehow better. And I think this is due to the fact they were producing sound live, just like us, and also because they have a physical presence. This was much more interesting and opened much more possibilities than the samples ever did.

Nelson- Finally, the world of visual arts developed an interest for these machines as well. And sometimes only for them. We got kicked out!

DS- Due to the nature of these machines, I believe there is room for variation and for the unexpected to happen. At least, much more than you had with the samples…

Marcos- We try to overthrow somehow the mechanical, monotonous aspect inherent to such devices. But, of course, there is also a fixed value which is the sound made by the device and the fact that this sound must suit our intentions for a certain piece of music. But, once this has been stablished, it’s all about creating variations. In order to achieve that, we use things such as timers that stop the whole device or certain parts of it. We also manipulate the sounds generated by these machines in numerous ways by using plug-ins to process them as a second layer of possibilities. From something very simple at its origin we try do develop a trajectory of changes by exploring this material in every way we can.

Nelson- There is also a great deal of randomness. We change strategies from time to time and according to each new project. Sometimes, it’s just Marcos and me playing, sometimes the machines have the main role, other times they only serve as a very discrete accompaniment. Last October, in a series of concerts in Germany everything was really controlled: “This machine will start playing there, and at this point I’m going to play this and Marco that…”. At the end of the tour, we were tired of this arrangement. Our last concert in San Franscisco was entirely diferent, much more relaxed. We tried combinations completely unexpected that we thought would never work before; all of the machines played together at once; then, none of the machines played anything… there was nothing stablished in advance.

DS- I saw the video of an exhibition you did in São Paulo and there were like ten devices functioning at the same time. This could lead to the impression of saturation, an overflow, but it was quite the contrary. There was still a great use of pauses and silence which I think is a very strong characteristic of your work.

Marcos- The sound that these machines produce are really complex in what concerns the timbre, but that’s pretty much it. It is what it is. And for one to really contemplate these sounds in their nature, more time is needed. So, in our work, time is dilated. Things change very slowly, but when they do, the impression is also bigger. Our music is not the music of a virtuoso. Therefore every note counts and the timbre must work above all.

DS- Your research with sound devices seems to be a search for new, interesting timbres…

Marcos- Yes, the timbre is very important. And it’s not an easy task to find these sounds. It takes a lot of time, a lot of research. It’s not every sound that we find interesting enough or that would fit our work.

DS- And I think your work in general is pretty much focused in this very “concrete”, almost tactile, experience of sound…

Nelson- I think I agree with you. Our work is very concrete, there is not much room for conceptualisations… The machines contribute also for this impression, I guess. They are a physical presence, they are functional. They are also a very straightforward representation of what you are listening.

DS- Back to the exhibitions, what do you think of them as a form of reception of your work?

Nelson- I think that one great thing about these exhibitions is that people have the opportunity to explore our work in a very freely way, literally walking around devices. Someone can approach one machine and then another… These movements give them very different perspectives on the sound of each machine and its relation with the others. At our concerts, we try to create this kind of immersion. They are usually quadraphonic. We try to put our audience “inside the music”.

Marcos- We love, for instance, when there is no stage whatsoever separating us from the audience.

DS- Working with cinema, you did the production sound on some of the films for which you also created the music. The fact of being on set, in the field, influenced your compositions?

Nelson- Due to other commitments, we haven’t been doing much work on the set. It’s very difficult for us to be entangled for a month in a film. Most part of the work with production sound we did was also for small projects with a small crew. To be honest, I sometimes found it very monotonous. Specially f you’re doing fiction, you know. Sometimes you wait for hours to shoot only for a couple of minutes.

DS- But during these productions did you at least record interesting wild sounds that could be used later in the process?

Nelson- Most of the time we did not have the opportunity for this. But, since you brought it up, recently we did the music for a feature, Joaquim, where the director, Marcelo Gomes, asked us to build our compositions using field recording material. So, we used a lot of things we had recorded way back, at the beginning of our career. And it was great! Although we don’t do much of it ourselves, I know there is a lot of great people doing wonderful stuff in this domain of field recording.

DS- I’ve read once a definition of your work as being a kind of “amplified minimalism”, where the word minimalism was due to the use you make of very small, delicate objects to create your sounds and amplified was referring to the kind of electronic manipulation that you do with this material. Do you agree with this definition?

Nelson- Well, first we should have in mind that there is already this very stablished movement called minimalism in music, with composers such as Steve Reich associated to it, based on repetition, very dilated in time… Our work has something of that. But minimalism in our case refers much more to the act of producing complex sounds out of minimum resources as you have put yourself. We are, in a way, much closer to John Cage than to Steve Reich.