Andrew Roth is a sound designer specializing in installation work– both sound design and engineering. He got his start at Earwax Productions in San Francisco in the late 1990s as an audio editor and expanded into radio, television, film and video games. Nowadays he still dabbles in film, commercial and video game sound, but his passion lies in sound installations. Some of his more notable work includes installations for Disneyland, the San Francisco Conservatory, the Smithsonian Institute, and Universal Studios.

You’ve got a pretty broad scope of experience from video games and radio to television and film. What was your first installation sound design work and how did it come about?

My first installation work was actually for Disneyworld for the Innoventions Pavilion at Tomorrowland while I was at Earwax. I was pretty low on the totem pole, so it was just making assets. I wasn’t onsite to do the actual installation work but I kinda understood about designing sound for a specific space rather than something like a game world.

The first one where I still didn’t do the actual on-the-ground installation work, but was more involved with the intricacies of the pre-show, post-show, UI stuff, creating the whole experience was a theme park in Florida called Wannado City. It was an underwater submarine sea base thing for kids. You stand in line, there was a pre-show and videos, transducers in the ground. I understood about multi-channel audio and distribution across several rooms and shaking the floor using bass tracks. The whole thing was about diving into the ocean and discovering sea creatures. It was kind of a mini-Disneyland kinda of experience.

The actual me buying all the stuff, getting in there and putting it all together was in San Francisco at the Conservatory of Flowers at Golden Gate Park. I created high-count multi-channel shows, upward of 24 discrete channels all playing simultaneously out of different things in a room. So I was researching how to inexpensively get that kind of a level of show for a small institution like that and then it kinda built from there.

So it sounds like your process has evolved as your jobs have evolved…

Yeah definitely. And it was really scary at first. I remember the first couple months of researching and calling upon friends who have done this stuff. Like in any creative field it’s a little scary when you jump into something new but it’s exciting and when you get over that little fear hump, then it becomes joyful. And then you wanna go bigger and get into animatronics and stuff. The next place I worked on after that was called Urban Putt, which is an indoor miniature golf/restaurant/bar experience. And I started with them from the ground up to design immersive audio in different rooms; every hole has robotics and mechanics. I started getting into all kinds of triggering mechanisms. I’d always been a tinkerer so this was great because it fused my love and passion of both sound and tinkering.

What is it about installation work that you love so much to consider it one of your primary passions?

In this age, I’ve gone through peaks and valleys of the game world and television where money comes and goes. There’s a lot of disruption in various media markets but if you find the right installation work, that’s hard to be outsourced because it’s right in front of you. I’ve found that installation work, while its very interesting to me because I love immersive and interactive audio experiences; also, it requires a certain skill in a space that can’t be outsourced.

What is your initial process when approached with a new larger scale installation?

First I think about the acoustics of the space and what’s possible. I think your imagination will run away and should run away but the first thing is what’s possible as far as the customer or user and their experience. If it’s a big room and the acoustics are really poor, I have to think about designing things more intimately or quietly. So the first step is what’s possible in here. And then there’s the brainstorming of how can I make everything happen and then the next step is how do you put those two things together. I mean there’s always the budget too, but I’ve found there are ways to convince even smaller institutions to extend their budget just a little bit to get real good multi-channel sound.

This just happened for me recently at the San Francisco Zoo. Most people aren’t thinking beyond surround sound, but when I come in and say “here’s a player, and just get this and a couple amps and we can have 16 or 24 channels and we can do different things over here.” And then you just need a few audio repeaters. Audio repeaters are the devices you use for interactive, randomized, triggerable sounds. It’s amazing how Arduinos and little technologies like that make these things possible for anyone now. It used to be the purview of larger institutions, but now it’s within the grasp of these smaller ones. You just need someone who has the knowledge, or desire, or the nuts…maybe I’m just crazy.

Do you use software to control your installations, or are you primarily hardware focused?

Definitely hardware. I know people who use Max, but I’ve never taken the time to learn it. I’m a fan of extending simpler systems. I have friends who do installation work and they’ll get a computer and use Max and run things off of the computer. But I’ve gotten so much into the hardware world and programming them even through basic subroutines, and I’ve found that the hardware is so much more robust. If there’s any problem, I can go there, but I don’t want any problems. At the Conservatory of Flowers it’s humid. Every time I clean a show out I have to sweep the cockroaches out of the amplifiers. Everything has to be super duper hardcore robust, flash-based. It gets rained on, it gets dirty. At Urban Putt, it’s drunken 30 year-olds and destructive 12 year-olds (with golf clubs!) and there’s a part of me that doesn’t trust a computer booting up everyday. I just want a chip and amplifiers and something that’s as destructive-proof as possible.

What are some of the biggest challenges you face when initially designing for a theme park, museum, or other large scale sound installation?

Aside from the basic thing of people not thinking about these installations in terms of audio needs, the first challenge is to not scare people off. “You know rather than playing a CD, why don’t we do this where I buy you 20 speakers?” The Conservatory has been great in that regard in that I just built a permanent multi-channel rainforest installation for that. And we just got some amazing washing machine-size subwoofers that we’re burying in the ground because there’s a simulated thunderstorm every day and I wanted it to sound great and not like the Safeway produce section. Once you’re specing things that are good for sub-zero or can deal with rain or insects or animals, dealing with a museum isn’t hard just as long as you can get them to buy into the vision.

Usually sound design is a more captive, directed experience, that is the audience is focusing on the actions creating sound. In a more open environment, I imagine there are more distractions for the intended audience which can add to the challenge of designing for these spaces. How do you try and ensure users are able to enjoy the sonic experience you have crafted for them?

You hit the nail on the head. That’s the hardest thing, especially indoor situations, which is the majority of what I’ve done. The cacophony of all the things going on, whether that’s the sounds I’ve designed, or crowds, air conditioners, everything in the room. So you learn about acoustics and treatment of walls and the directionality of speakers and how they’re oriented. Sonically, just like colors, you realize that you’ll get more through a use of higher frequencies and being more conservative with your lower frequencies and only using them in certain areas. For example, in Urban Putt there’s a submarine in an underwater room so you get a whole lot of rumbling, there’s transducers in there. For the water outside of the sub, it’s in the same room, but you take all that bass away because you know people will register that difference. It’s funny people tend to think the same about audio as they do visuals like if you don’t see it, you won’t hear it. I’ve had architects suggest to turn a speaker around so you don’t hear a sound over there. And obviously it doesn’t work that way, it may filter the sound, but the sound will still propagate throughout a space. So sonically you design by the frequency ranges that aren’t going to clash with each other. And also taking turns. You want people to walk in and have all this stuff going on, but people can only concentrate on one thing at a time, so maybe I only have a third of the things or half of the things going on at a time and they’re cycling between these sets of sounds and spread out in a way that provides the experience without sounding too cluttered.

Sitting at the Conservatory of San Francisco was great because I could actually sit there and watch peoples’ reactions. The Disneyland one I could never sit there and watch what people did. But at the Conservatory I could see what people would react to and notice or wouldn’t notice. It was really educational. As a sound designer, as I get older, even though there’s an infinite number of tracks and sounds and textures, what I keep coming back to is old sound, like movie sound from the 30s and how they have such a narrow sonic range, so they just play a certain sound effect here or a certain music cue there in a very obvious and clear way. I love doing textures and getting complicated and all that, but in installations, you really see how you have to be so specific and uncluttered in what you’re trying to get across in each speaker, in each moment.

I’ve been fascinated by Disneyland since an early age in that regard. I just got back from there with my family and at one point after they all went back to the hotel, I spent some time walking around like some creepy middle age guy just listening and looking at where the speakers were and how the show was constructed both in the attractions and ambient wise. Everything is very specific. At Splash Mountain, there were speakers about every six feet as you’re going along. And that’s a lot of speakers! But that’s how I sell it to people who don’t really understand. Like a museum or somewhere they may not be thinking about sound so much. The Zoo was like this. They think the more speakers, the louder it is and I have to explain that the more speakers the quieter it can be because you don’t have to have one speaker over here playing to someone twenty feet over there, so you can keep the volume down and it’s more even across the whole soundscape.

It’s interesting that with the rise of VR now, you’re using a lot of similar concepts of 3-d audio but in a real, practical environment rather than as a binaural image. Having these multiple speaker arrays seems to afford you the ability to do object-based sound and true 3-d audio immersion.

Yeah I’m really interested in that. I mean there’s so many different delivery formats. There were a couple jobs where I wanted to hear the virtual space binaurally but then still have it programmed up for all the different speakers. There’s some great software coming out from Ircam called SPAT Revolution that lets me do that, so I can spit out A-format or B-format. I can lay out my mix as an object-oriented thing like Dolby Atmos.

Are there additional design considerations based on the location of the installation: i.e., a crowded theme park, an outdoor park, and indoor conservatory, etc. that you need to account for when planning and designing for these exhibits?

As I said before the space itself is the biggest deal. But the ambient sound of the space itself is important as well. Is it going to be a crowded museum or a quiet place? I did an installation at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, and I could be very subtle because I knew there would never be 100 people in the room with lots of crying kids. But on the other side of that is a place like Urban Putt, which is nuts. There’s people playing golf and alcohol and robotics and smells being pumped in. So almost anything ambient is kinda useless there because it’s such a loud environment. There’s no point making a subtle, beautiful ambience because the ambience of the space itself is so cacophonous.

So it feels like your work is generally either in quiet or loud environments. Have you been able to play with dynamic range in your work when you’re generally dealing with two extremes?

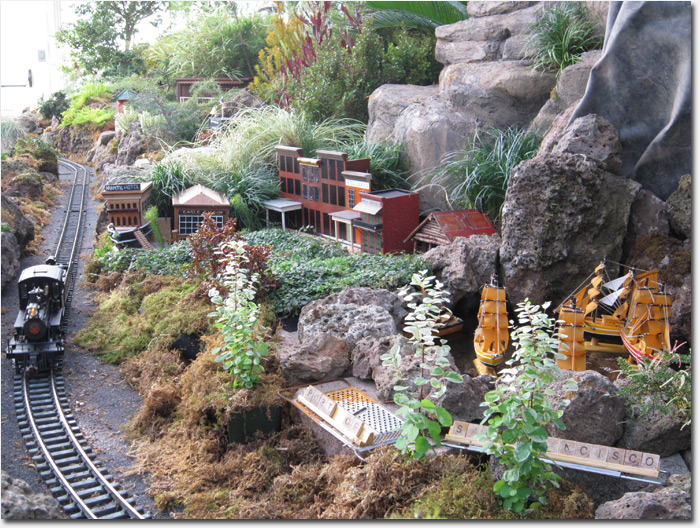

I think it depends on the show and what you’re trying to do. Urban Putt has multiple rooms, so when you get them into a smaller room, you can start focusing the sound a bit more and grab them and do different things. The room itself is quieter than much of the rest of the environment. Even the Conservatory, for the Garden Railway exhibit we had all these natural San Francisco sounds, and we had a single musical piece that would move throughout the room and then once an hour, there would be an earthquake. So the subwoofers start to rumble and there’s a glass ceiling and I put speakers up there and played breaking glass sounds. And then it would just get quiet. And one thing I love about those shows is that it can feel like this big space with all this stuff happening and then you just press stop and the whole room becomes this little room again. That’s another thing that helps convince museums as to the power of sound in their installation work, is how much it transforms the space.

But in terms of dynamic range, I had the huge crashing sound and it’d be quiet, and then there would just be this one famous fountain you’d hear. So I’d sculpt the room to be loud and quiet just as you do in any sound design job. That was fun. But they told me never to do that again because it was really scary for some people. With the rumbling and glass breaking sounds people ran out of the room thinking it was a real earthquake!

What’s been your favorite experience in doing installation sound design?

I think because I have a big love of history, it’s gotta be some of the historical shows I’ve done. It’s given me an excuse and a calling card to go to obscure places and record obscure things. We did a Playland at the Beach show where I drove out to Carson City, Nevada with my wife to record the actual organ that was at Playland (a now defunct amusement park in San Francisco) that’s now in a private collection in this guy’s basement that he built in the desert. That was just so everything could be accurate and authentic. A lot of times I could get away with faking it and a lot of installations do. But especially when it comes to music and certain historical shows when you really want to create a special feeling that doesn’t sound like off-the-shelf sound effects. What does it really sound like? What were the real things? That’s been the most fun.

For the Gold Rush show I recorded my friend playing an old melodeon from the 1860s. You can make up the Gold Rush: throw in some horses, some creaky boats, some people yelling and all that kind of stuff. But if you get each of these elements and each thing sounds a little different and you put them all together, there’s something different, there’s an atmosphere. For me I know it’s more realistic, for someone else it just brings them in a little bit more because it’s not the exact sound they were expecting.

What similarities and differences do you see in installation sound design vs. Linear media such as films or interactive media such as video games?

Well in video games and film, there’s something being created by an editor, a producer, a director, etc. that I need to adhere to. So I’m enhancing and helping to tell the story which is in front of you. And in an installation, you’re doing that but you have much more control, even if it’s someone else hiring you to do something and it’s not your original idea. You have much more control over the experience, how someone is experiencing the story because it’s nonlinear and you can decide, “I’m gonna play this music here and get them all jovial and then hit them over the head with this thing over here.” So you have more leeway and greater command of being a storyteller even if you’re still a hired gun.

Again it goes back to Disneyland. The whole thing about Disneyland is creating this idea that every step of the way, everything you hear is a story being told in space.

What would you like to do next in the way of your installation work?

I’ve gotten to do slightly larger and larger venues and I hope to keep doing that because there’s only so much you can do in a single room no matter how big a room is. Like at Urban Putt there are multiple rooms and I think they’re going to build another one in L.A. that’s going to be split up more and that just allows for more discrete chapters of sound.

Beautiful, so inspiring!!

As I’m in love with sounds installations (that tell a story) and made my most important piece jsuat recently, I was wondering if Andrew would be able to answer a couple of questions.

Cheers

Axel

What a great interview, both the questions and Andrew’s responses are so insightful!

I especially love the idea of the “movie sound from the 30s” sound design approach.

Thanks for the great work!

Best,

Hyphen