[Author’s note: much of what I describe below could be construed as “reactive audio,” not “interactive” because sound is most often reacting to other systems and world parameters rather than directly affecting them in a feedback loop. For the sake of brevity and sanity I will refer to both reactive and interactive sounds below using the widely accepted and used term of “interactive audio.”]

The sculpting of the relationship between sound and an environment or world state is perhaps one of the greatest powers we hold as sound professionals. Obviously this is often conveyed in linear media via music. Think of Bernard Herrmann’s strings in the shower scene of Psycho, Wendy Carlos’ score in The Shining, or the “ch-ch-ch ha-ha-ha” foreshadowing a grisly Jason Vorhees splatterfest. Even the subtle, otherworldly sound design within a surreal tale like David Lynch’s Lost Highway grounds the inexplicability of the plot into the strange world in which it occurs. In each of these examples, the sound is at least as critical as the visuals to make the audience feel something. But the sound and visuals are the same every time, meaning we get the same experience with every replay.

With technology, we have the ability to extend the power of audio into interactive mediums, and we’ve been doing it for years. It is this direct relation between user actions and sonic changes that provide feedback to a user that something is happening and this is the kernel of effectiveness which we call interactive audio. Let’s explore some examples of interactive audio across a few different mediums and look at how these examples affect the user and what responses they evoke.

Games

Video games have been kicking around the term “interactive audio” for years, most frequently in the realm of music. While this is usually a means of “action changes, so the music responds to these changes,” there are several examples where audio has a more tightly integrated, and thus effective, approach to interacting with player control.

The quintessential example of interactive audio for most people is Guitar Hero and its spiritual successor, Rock Band. These are also prime examples of music being the driving force of interactivity because these games are, in fact, music simulators. You play along with a song performing similar-ish actions to musicians. Pressing buttons in rhythm to the music rewards you with points and a successful round. If you mess up, you hear your error through sound effects and music dropouts which simulate flubbing a song while playing it live. Even Harmonix’ earlier games, Amplitude and Frequency used a similar gameplay mechanic with a similar reward/failure loop tied directly into music performance. Interestingly, while audio interactivity is ingrained into this style of gameplay, we see most of the unique bending of the sound to player actions when the player performs poorly. Only in failure does the song sound different than if it were playing outside of the game space. From the standpoint of the game’s directive (make the user feel like they’re actually playing these songs), it makes sense. Play perfectly and you’ll be rewarded with the feel of “I did it! I played Stairway to Heaven!” Fail, and you get the feeling that you need more practice.

Parappa the Rapper

Before Guitar Hero there was Parappa the Rapper, the Playstation rhythm rapping game that was all about pressing a button to the rhythm. But even something as simple as Parappa introduced the ability to “freestyle” your rap by pressing buttons in rhythm beyond what the game instructed you to do. Doing so would give you bonus points and also transform the soundtrack into something with a new, remixed feel. This interactivity provides several layers to the game: it adds a new dynamic to the soundtrack, which is normally the same 2 minute song played over and over until you move on to the next level. It enhances the difficulty and player satisfaction by challenging players to try and be creative in how they press buttons in a game whose main mechanic is to follow onscreen instructions. And it promotes replayability by giving users a chance to do something new and different in each playthrough. Not bad for a simple sample trigger!

A more complete example may be the game Rez. Initially developed for Dreamcast and ported to PS2 and more recently PS4 and PlaystationVR, Rez has the look of a wireframe old-school arcade game like Tempest with mechanics similar to the 16 bit arcade classic Space Harrier. In Rez your character pulses to the beat, a simple scaling trick which instantly roots the music into the action of the game. Rez was pretty revolutionary for its time because the music itself changed based on what you were shooting and what was spawning or being destroyed on screen. The music was all 120bpm, 4/4 electronic music, and the way the player attacked the objects on screen gave the music the adaptive ability to retrigger loops, change instrumentation, or play sweeteners on top of the score. It’s pretty fascinating to watch playthroughs of the game and hear how every game session sounds different. The way the player chooses to attack will completely affect the music structure and samples used. Similar to how the player “remixes” the Parappa vocals by pressing buttons, players in Rez are essentially remixing the soundtrack to the game (both sound effects and music) by playing the game. It is the player’s input that affects the audio output we hear.

Rez

Thumper

Thumper is another rhythm action game where the music, sound and visuals are all so cohesively tied together that it feels “right.” You get sound when you expect it, and it matches the flow of the visuals. Every time you turn a tight corner, the track itself flashes, and the flash matches a swell in the music. Each power up or enemy destroyed provides a satisfying low frequency hit or music sample that matches the percussive feel of the action onscreen and ties seamlessly into the game’s pulsing score. Pitch and beat stutter effects are also present in the game play that all affect the game’s score. Tying sound into the onscreen action not only sells the action better but also emphasizes the relationship between these aspects of the game and our core information senses of hearing, seeing, and (sometimes) touch. More on that in a minute.

The videos above do not really do justice to the interactivity of the experience because the relationship is so intimately bound between game and player. To someone watching a video, it just looks like a video game. But to the player experiencing the lockstep relationship between audio and gameplay it becomes something new; a more complete experience.

It also bears discussing the interaction between animation and sound further because it is a highly effective, thoroughly underused way to enhance intended mood. Whether stark or whimsical, audio tied to and interacting with the visuals can lock the action of a game deeper into the soundtrack while also pulling the user further into a sense of immersion. From the automatons marching to the beat in Inside to creatures bobbing their heads to the score in Rayman to Sly Cooper’s marimba footsteps when sneaking around in a barrel to the music layers triggered when doing a super-powered jump in Saints Row IV, music or sound effects tied to animation enhance the play experience by tying the sonic palette to the wider scope of the world and its gameplay.

Linking sound to actions in the world and having sound react to or interact with game state helps provide focus to a game and creates a sense of tempo in the action. But why is this the case? Naturally, the answer lies in that bag of gray matter sitting in our skulls. Cognitive scientists have been studying the phenomenon of multi-modal and cross-modal processing for years. Multi-modal processing is the act of multiple senses all providing information to the brain about a stimulus, while cross-modal processing is the act of one sense affecting the perception of another. For example, there have been studies showing playing audio cues during visual stimuli can make the users think they see visual cues that are not there. Therefore sound can imply visual data in certain scenarios. That is power! Various studies have also shown a more complete understanding of a situation when given clues or information through more than one sense. While there haven’t been any studies (that I know of) specifically looking at cognitive brain function and the use of interactive audio, I hypothesize that audio interacting with visual and game state stimuli make multi-modal integration tighter and therefore enhances perception of these events.

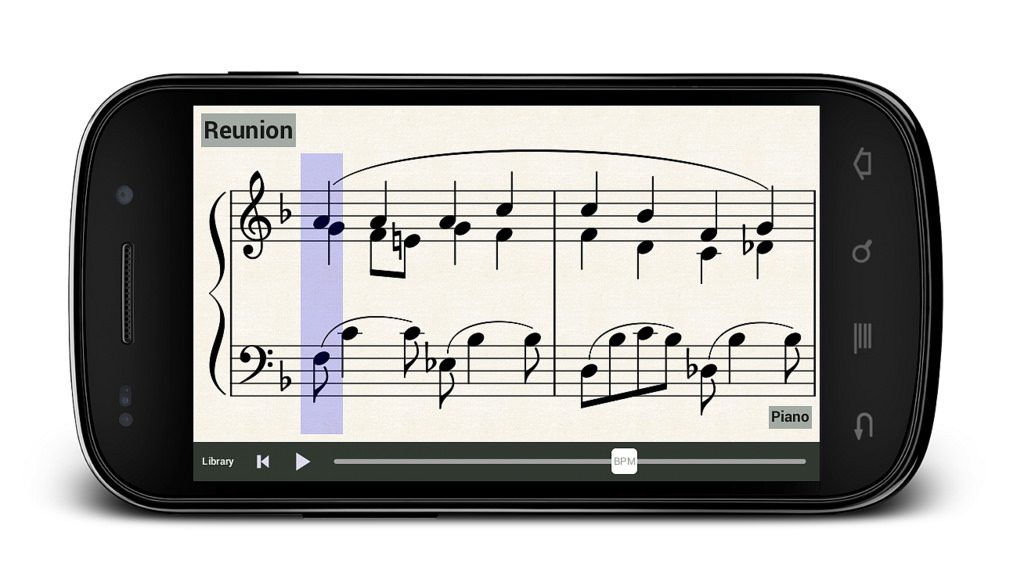

Apps

Computer and smartphone applications have been another place where we experience interactive audio. Any audio enthusiasts above a certain age group may remember the early web sensation that was Beatnik. Created by former pop star, Thomas Dolby, Beatnik allowed you to remix music on the fly in a web browser. Pretty revolutionary for the late 90’s! Nowadays we’re seeing similar, more sophisticated applications on smartphones. From the DJ Spooky app which allows you to remix your entire music library to the audio app for the movie Inception which produced a generative score based on player location and action, we are seeing these tiny devices creating compelling, iterative experiences for users through interactive audio.

DJ Spooky app

Turntabalism and DJ mixing are excellent examples of (formerly) low-technology interactive audio. With 2 turntables and a mixer, a person can take two pieces of music and transform them on the fly into a singular new composition. The DJ interacts with these two pieces of vinyl (or CDs and mp3s nowadays) and creates a wholly new experience from this interaction. Using these skills as a jumping off point, DJ Spooky, well-known DJ, musician, author, artist, and busy bee, helped create an app which allows a user to utilize these same tools to remix their entire music library. Using controls and gestures on a touchscreen users can mix, trigger samples, play loops and even scratch samples and music from their own library. It’s a fun, dangerously addictive toy/performance tool and what keeps users coming back is the interactive nature of manipulating linear audio. The interaction between the user’s fingers and their music collection, slowing down a track, scratching it, or firing off a specific phrase at will to create something entirely new used to be an art that took years of practice and lots of gear to master. Now it all lives in a few dozen megabytes on a tiny phone or tablet and provides users with an instant ability to mix and remix any sound into something new.

Inception

At the time of its release, the Inception app, a free iOS movie tie-in download was dubbed an “augmented sound experience.” Created by the innovative team at RJDJ, it combined samples from Hans Zimmer’s score with smartphone technologies such as GPS, accelerometer, gyroscope and microphone and DSP technologies such as delay, time stretching and reverb to make a truly interactive application. The premise of the app is that you unlock “dreams,” which are sonic textures created from the score and heavily processed. As you do things in real life, the app begins playing these textures processed in a suitable way. For example, if you launch it after 11pm, it begins playing really spacey, dreamy textures with layers of post-processed delay. Other tracks and effects are only unlocked with other special events, like being in Africa or being in sunlight, each with its own unique experience. Similar to augmented reality games, but audio-centric; your experience of the app is what you hear and it in turn is affected by elements like location and time. Your very being, where you are or when you are, is the driver of the changes you hear in the sonic textures. If you have an iOS device, you should download and play with it yourself to get a glimpse into certain ways we can affect a user’s experience with various parameters and technologies around us.

H__R

RJDJ also has a newer app currently titled H__R (apparently there is some litigation regarding its name; it’s looking for a new name now) which gives the user control over these features a bit more explicitly. With H__R the user puts headphones on and is given a series of presets such as “Relax,” “Happy,” or “Sleep.” Each has sliders the user can play with to affect the sound input of the microphone. Select the “Office” preset and you have sliders to control Space, Time Scramble, and Unhumanize. You can use these sliders to dampen and filter the sound around you making it sound like you’re in a big space with lots going on or you can zone out into your own quiet time. You are effectually tweaking your mix of the world around you. This app is especially interesting because of the way it tweaks your perception of everything you hear with some sliders on your phone and some clever under the hood DSP. It’s yet another example of how interactive audio can affect the way we hear and create a new experience in “the real world.”

Installations

One last area where we’ve seen a lot of interactivity is in art installations. I find these the most interesting because unlike games or other media apps, they involve a bit more human interaction, not just via fingers or hand gestures, but humans moving around to experience the way sound interacts with the environment. While art installations incorporating interactive sound may often be relegated to art galleries and workspaces, they also challenge the ways we perceive and react to audio in more interesting ways.

An example which we may see outside of galleries and in places like public parks is a whisper wall or other means to concentrate and direct vocal sounds to a listener far away from the speaker (see the image above). While this is technically just a demonstration of physics and sound propagation it is also a means of architecture driving interactive audio. At the “Murmur Dishes” installation in downtown San Francisco, I have seen people walking down the street stop what they’re doing to begin interacting with the sculpture. One person going to one side, the other on the opposite side and talking quietly while staring back at each other in amazement with that look in their eyes of “Oh my God! I can totally hear you right now!” This is an interactive sculpture with audio as the feedback of the experience. Users rely on the audio to prove to themselves that this seemingly aural illusion is in fact real, and it is through audio (sending and perceiving speech) that the users interact with the sculpture.

Let’s look at another example of an art installation incorporating interactive audio to get a better understanding of how audio can be used to affect user experience. Anne-Sophie Mongeau, a video game sound designer and sound artist, created an art installation which was a simulation of the experience of being on a large sailing ship. The exhibit featured a custom 11-channel speaker layout playing back sounds around the exhibit to simulate various ship sounds from the creaking of the deck to the wind in the sails above. Weather including wind and rainstorms would randomly occur periodically while visual projections supported the changing weather and the ebbs and flows of ocean movement. In the middle of the room was a ship’s wheel. Invariably people would gravitate to the wheel and see if it moved. Indeed it did and every turn elicited a heavy, creaky, wooden “click” from a speaker mounted at the wheel. The more someone would turn the wheel, the quicker the weather patterns would change. Anne-Sophie designed this system using Max/MSP, which is a fantastic tool to create complex dynamic audio systems using internal or external logic or controllers.

Adding the wheel and its interactive components transformed the piece from a passive art installation into an interactive experience. Users were no longer walking through an exhibit and hearing waves and sails. Instead, they were on board the ship, steering it into and out of squalls. The immersion of interactive audio can be exhilarating, especially when it is taken out of the living room or the screen and propagated to a larger venue.

One may be tempted to infer that interactive audio is so effective because we are used to static (non-interactive) audio, but in looking at various forms of popular media, we are seeing more and more examples of interactive audio everyday. Their effectiveness lies in how they tie into other systems and also how they provide instant verification that player action is affecting the experience whether that’s at home on a console, on our smartphones or at a museum. This has long been the appeal of interactive audio, to craft an experience and have it adapt to user behavior, and I expect we will continue to see new applications and implementations of audio as a driving means of interactivity continue to mushroom.