From Design to realisation. Sound Design concepts should exist throughout. Photo: Pexels

Sound design in VR presents any practising professional with a remarkable array of challenges as they begin, work through, and reflect on any VR projects that they work on. As designingsound.org is focussing on Pure Sound Design in the month of August, I thought I would share the approach I take to my sound design at my workplace Zero Latency. I’ve been working in house with Zero Latency since March 2016 (about 6 months), and have had the opportunity to establish and iterate on my own practice and pipeline. ZL has it’s own caveats and challenges that it presents (our tight time frames are a big one, the multiplayer free-roam nature of the system another), but this presents an excellent opportunity to discuss the way that planning and prediction of player experience can and should impact on your sound design practice.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]… this presents an excellent opportunity to discuss the way that planning and prediction of player experience can and should impact on your sound design practise.[/perfectpullquote]

Compressed timelines mean that sound design might have to occur in-step with the rest of the game development. While this can be a sound designer’s dream come true, it can make it very difficult to scope your work. When you only have 6-8 weeks to develop a project, scope and staying ‘relevant to design’ are critical to your time management. I’d like to share a few of my spatial and temporal planning techniques, as well as some of our general philosophy behind shaping the ZL sound experience.

Planning a VR Environment

When approaching a new VR project, the rush of ideas when discussing the concept and gameplay is a heady cocktail that can give you a push in the right direction early. Concept art, reference material and general creativity all convolve to facilitate a rapid process of sound ideation. It’s easy to get wrapped up in this, but one of the best ways to allow for all of these ideas to be catalogued is to actually catalogue them. It’s no secret that audio folk are excellent documenters, and with VR you can also map out your plans (as well as creating your spreadsheet).

The environmental audio (ambience) can be mapped when the level design and construction is complete, giving you a physical form to help shape the 360 degree audio world. Creating visual maps of the audio environment can help to create evenly paced (or purposefully unevenly shaped) audio environments and can help to clarify focus points that will help guide players, or help to collaborate with artists on creating elements that help enrich the player’s experience of the game.

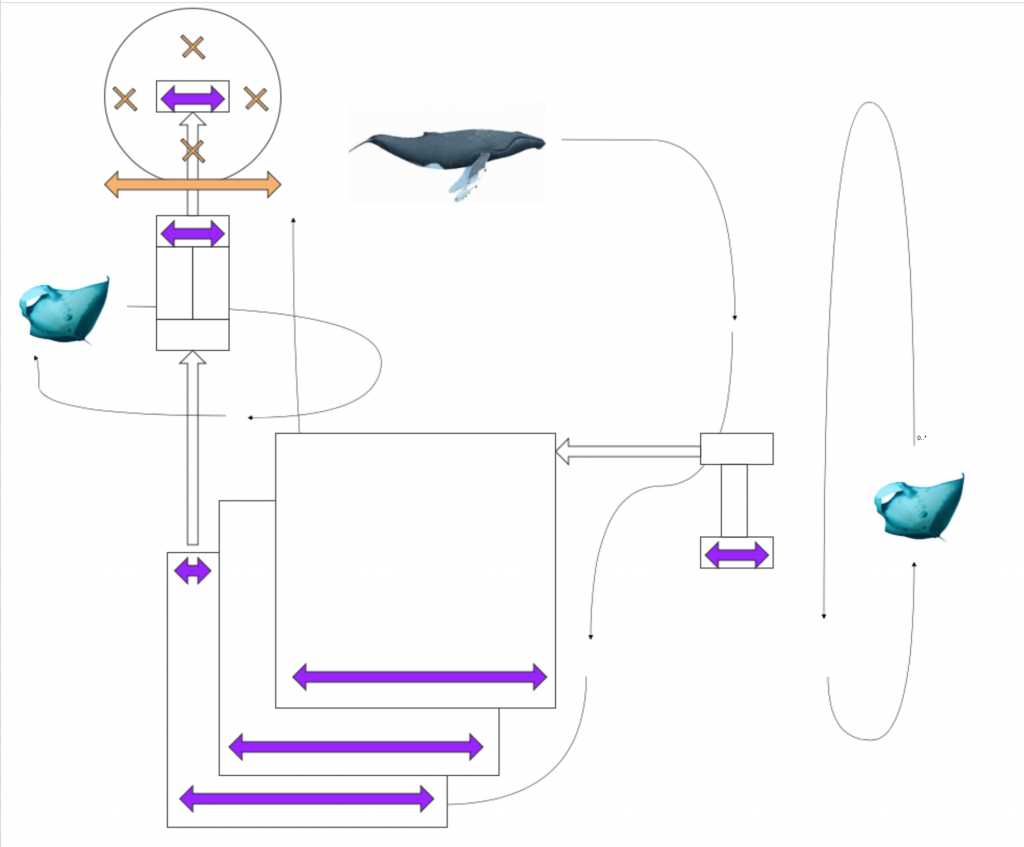

– Spatial map of Engineerium – featuring basic level features, music trigger points (purple) and sound trigger points (orange).

The environmental world of Engineerium features a huge array of visual and auditory elements to immerse the player very efficiently. With a play time of 12 minutes for this title as well, set dressing (visuals) and the ambient audio environment is hugely important to enhancing vibrancy and transporting the player quickly into the world of the game. This is true for any game, but particularly for Engineerium, the interactable world is suspended high above a vast uniform ocean, and the focus we wanted to bestow to the player meant we wanted to limit the number of interactive elements to those purely critical for the game to be completed. This meant that the world needed the implication of diverse lifeforms through the audio ambience, but at a distance which does not create an expectation to take visuals of the creatures.

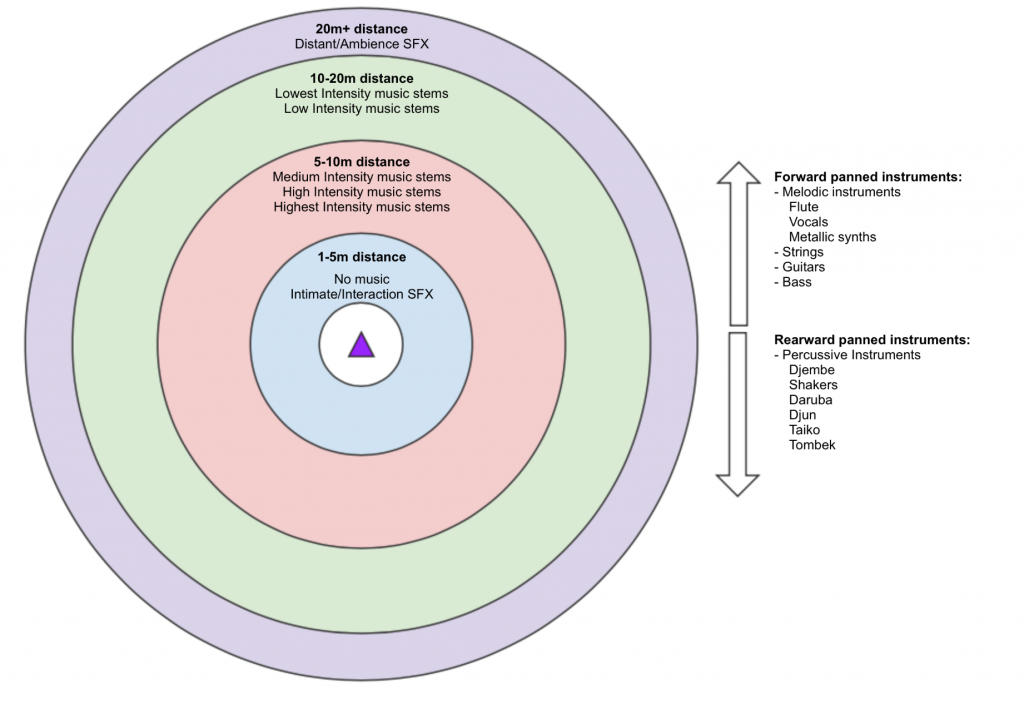

The spatial work of Engineerium includes randomized and scattered animals and environmental elements, as well as the fixed “ocean” and “sky elements” and triggering points to manipulate the mix of the animal based environment with the water based environment (based on the proximity to a major water feature). This spatial plan was then layered with a spatial plan for the music, which was important for giving all elements in the audio space (to avoid competing), and was very constructive in communicating how the intensity of the music should develop (in both energy and spatially) with the composer.

– Player-centric map of audio ‘zones’ outlining the movement of music (relative to the player and SFX).

Macro Sound Design

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The ‘macro sound design’, or what some would consider the overall sound ‘direction’, prompts you as the designer to consider the overall feeling or experience that the players will take away from the game. [/perfectpullquote]

Players can die as often as their skill level allows, but all players essentially ‘win’ the game. To make this design, all interactions the player has had to be heavily curated to feel ‘natural’, ‘powerful’ or ‘creative’ (depending on the genre of the experience). This often means that the players need to be delivered critical information at the right time, without fail, and the audio delivery is one important element of this. For each project, defining the philosophy allows you to define how player interacts with the world, and how you will allow them to feel success and enjoyment in the experience.

Taking the example of the ZL project ‘Zombie Survival’, which is a 12 minute long tower defence style project where players are dropped in to a fort with the promise of a helicopter rescue at the end of the experience. In this project, there is essentially only one moment that is critical for the players to achieve ‘success’ – they need to board the ‘platform’ that the helicopter will use to lift them to safety. Knowing this, and that there would be four waves of zombies delivered to the player, the audio plan formed as follows:

Beginning (0-4 minutes) = establish audio environment and ambient intensity, use VO to establish ‘survival’ concept so the players can be rescued

Middle (4-10 minutes) = build intensity of audio environment, consistent build of ambient intensity, use VO to destabilise the players and introduce other deployments that get ‘taken’ by zombies to make them feel uneasy.

End (10-12 minutes) = peak intensity of audio environment, peak ambient intensity, introduce chopper with a passby and use persistent VO to time the rescue and direct players to success.

Using the audio to build ambient intensity, and crafting a VO script that builds tension towards the peak ‘rescue’ contributes to the ‘frantic’ and ‘overwhelming’ tone of the general experience, which in turn leads to a greater sense of success when the player completes the experience.

From Design Philosophy to Design Execution

A thorough spatial plan for the audio of a project makes the initial sound design and implementation a matter of iteration and certainly gives you the opportunity to develop your direction and purpose for the overall sound design of your project. Planning a design philosophy around the player’s resulting experience does cue you to start considering the way in which the player’s potential interactions and behaviours, and how that will impact and form the design of your sound.

The most significant reason for a experiencing a divergence between the planned design, or expectation, and the ‘reality’ of the final design is the way that non-expert non-developer players interact with the world. Within ZL projects, it has been noted that regardless of the design theory behind the audio design, music or mixing, non-expert players need a heavy amount of guidance and curation to guide their attention and experience – particularly since ZL moves the players through the system in groups of 6-8 players at a time.

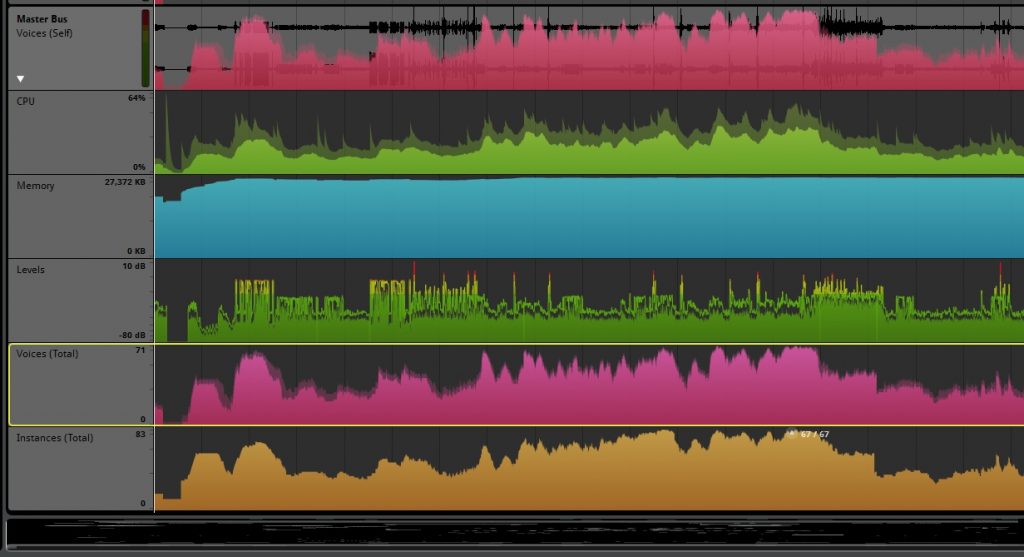

In the ZL paradigm, 6 players caught in a large scale firefight (for example) generate a large number of sound sources, and (in this example) a high SPL for each player as well. It is a generally accepted philosophy that ‘overcrowding’ the aural field of a listener will cause a loss of definition from temporal and spectral masking, making the individual (or even important) sounds impossible to distinguish from each other. In films and other linear media, and even to some extent, video games with single player or controlled multiplayer modes, it is possible to mediate the experience of the player or viewer. However, in larger scale multiplayer games, and certainly in the ZL paradigm where each one of the 6 players in the game might overreact to a large number of enemies at the same time, there is the potential for huge explosions in voice numbers and volumes presented to the player. The image below is a capture of a play through for just one player, note the voice count hits around 70 voices.

Developing a methodology for approaching moments like this can help to ease player confusion and guide the player through the experience more effectively. At ZL, we leveraged the 1st person/other player perspectives to trigger mixer effects, as well as sharp attenuation curves for sounds like gunfire, and deliberately well designed mixer hierarchies to ensure that sounds heard by the player only could be impacted when required. All these elements become a part of the sound design in VR projects, because capturing the essence of the sound can be considered impossible without expressing the relationship of the player to that sound. Much like the way in which you might repeat an action with varying intensity or speed to analyse the sound and how it expresses your interaction, players within your VR titles expect relevant feedback with the environment and VR world around them.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]…these elements become a part of the sound design in VR projects, because capturing the essence of the sound can be considered impossible without expressing the relationship of the player to that sound.[/perfectpullquote]

Extending your sound design practice to include planning for spatial design and player interaction allows you to express your design practice and methodology more extensively. This is a widely useful practise when approaching audio in VR, as the extra layers of immersion and the necessity to guide and mediate that immersive journey do require a more deliberate application of our sound design skills. These elements and practices were developed as a result of the system which I develop for. Many of these practices are applicable to other multiplier VR projects, and particularly in free roam systems like the HTC Vive as well. Some of these techniques can even be scaled to work for seated, fixed position VR experiences as well, as the role and positioning of the viewer (or visitor, or player) is different for every project.

Sally Kellaway has a clone that constantly lives on Twitter @soundsbysal (jokes! She wishes but she has to do alllllllll the twittering herself).