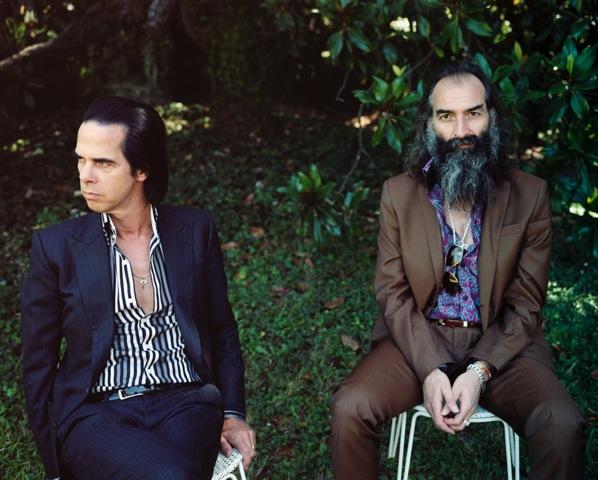

Warren Ellis is unstoppable. The busy Australian is a member of – at least – three different bands: The Bad Seeds, Grinderman and Dirty Three. He plays violin, piano, bouzouki, guitar, flute, mandolin, viola and, yes, probably even more. He is pretty much constantly touring the world, making records or creating soundtracks. Anyone who’s experienced him onstage with Nick Cave knows his powerful presence and amazing musicianship – he’s been a member of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds since 1994.

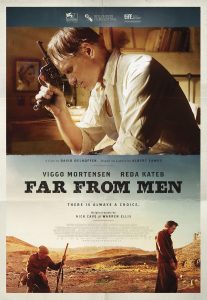

Together with Nick Cave he’s scored several films, among these The Proposition (2005), The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), The Road (2009) and just recently they did the score for the French drama Loin des Hommes – Far From Men is the UK title – which is based on the Albert Camus short story and set in Algeria in the years leading up to independence.

This month’s theme here at Designing Sound is Destruction and Ellis is someone who’s not afraid of gritty, noisy, textured, explosive, destructive sound – his approach to sound is often to use accidents in creative ways. Here he talks about his methods and inspirations – and why he loves cinema:

WE: The thing I like about cinemas is that they have this fabulous sound system, so with sound you can really go to town with the sound design. Most of the music you make with bands today, you know it’ll be made into an MP3 and put through a set of speakers the size of a keyhole. That’s a fact of life, it is what it is. But last night I was at the cinema where Loin des Hommes was screened and I could fucking hear the sound coming through the walls and it was fabulous. I love that about the cinema. It’s one of the last places for that. Rock concerts and cinemas are the places left for that, so it’s great to be able to make music there.

DS: The movies you work on are very different but you can tell that the directors listen.

WE: I think that anybody who wants to work with us knows what we do. They understand the history that went on before, whether it’s The Bad Seeds or it’s the cinematic language that we use to discuss now. We have a broad base now of both our existing works. But I think that if they’re aware of the history, they already have an idea of where to go. They know that it won’t be a background thing to fill out an emotion. Certainly, when we’re making the music it’s never about that. It’s never meant to override or take over a scene, but it shouldn’t be just a wallpaper or glue. I remember doing The Proposition, it was very fast and over in something like four days, bang-bang-bang. Ten-eleven hours in the studio, idea after idea. Watching the film once and then literally trying to make something. I think in the end of it, there were ten CD’s of ideas. Some were great, some were crap, but it was just idea after idea. At the same time, an editor would sit there and try to cue and try to put a body in. He’d say something like “I think we can get a cue in here”, so it was done in a very rock’n’roll approach. It was done in four days, five days at most.

Jesse James was the next one we did and the movie blew me away by the presence they’ve given the music. It was so loud and not underwhelming at all. It gave it a life and a purpose of the film that I hadn’t anticipated. It was the first time that the people who knew what I did, who went and saw it, it was the first time they came up to me and said wow.

In Loin des Hommes all the basses for the pieces were formed using champagnes bottles, blowing across the tops of magnums of champagne, putting them through effects. I had an alto flute that I de-tuned and I wanted to think about the structure of these hip-hop records or the latest Kanye West-record where you have these really extreme sounds that cut it. The soundtrack doesn’t resemble this, but in the back of my mind, I thought that could be an approach to apply to the score. So suddenly I get these super-low flutes that are pitched two octaves down because I put them through an octave-pedal, cutting in like they do on those records. I used anything but standard instruments to generate those things. Afterwards Nick got the melodies going and we put some chords in, but for me these sounds provide a big canvas to paint something hopefully quite different. I find that very challenging and exciting.

DS: It seems like you’re constantly exploring sound and sonic approaches.

WE: I love making music. The thing that drove me to making music was because I enjoyed it. As a young kid I played classic violin, I loved rock’n’roll, but I didn’t see the connection between making music and enjoying it. I always thought I’d be a music fan. For as long as I can remember, listening to music was a way for me to escape the world. I’m fifty now so when I was a kid there weren’t many escape routes. There was television, music, film. You couldn’t see a film whenever you wanted, I lived in a small town. Music was such a focus for me and a precious thing to have. There are records where I know every inch of the cover, every detail. But somehow I found myself making music in my mid-20’s. I was never monetarily driven, I just loved playing.

DS: For me it often seems that both in soundtracks and The Bad Seeds, there are instruments that I recognize, but there are almost always one element or more that I can’t recognize.

WE: Yeah, The Proposition was the first time I really ran amok in the studio. I had a bunch of amplifiers and loop stations. I’d been talking to Bobby Gillespie about producing Psychocandy, the Jesus and Mary Chain record, and how they got the sound that every time you heard it, it just ripped your head off. How did they get it to sound so amazing. And he couldn’t remember much, but he remembered that there were three different guitar passes they just kept taking up and down. I couldn’t get this out of my head, so I thought, well, why don’t I just take three different amplifiers – a big one, a little one, and a direct line. The recorder had never worked in this way before, so we recorded four passes of everything through different amplifiers and then we’d start it off and listen and raise something up. New overtones would come, it was the same pass, then bring this up and pull this down, raise up another one and it gave these atmospheric shifts. It was a fantastic discovery. It was the beginning.

Then Nick and I had this talk of applying this freedom into our musical band and that was the idea behind our other band, Grinderman. We let ideas through which we normally wouldn’t because The Bad Seeds would have a lot of rules. We tried and start as fresh as we can and we developed this approach – I brought a bunch of stuff in there and we just made music for days on end. Half the time I didn’t really know… Recreating some of those records live was hard because I didn’t note anything down.

Then Nick and I had this talk of applying this freedom into our musical band and that was the idea behind our other band, Grinderman. We let ideas through which we normally wouldn’t because The Bad Seeds would have a lot of rules. We tried and start as fresh as we can and we developed this approach – I brought a bunch of stuff in there and we just made music for days on end. Half the time I didn’t really know… Recreating some of those records live was hard because I didn’t note anything down.

I ended up in this mess of cables, because I could have twenty or thirty different panels, ten or fifteen instruments, I’d just grab things and stick them in and it was all in a tangle. Everything was in a mess. I’m not taking pictures of knobs to see how they are, so half the time I don’t really know what the sound is. I’ve had instances where I’ve done things, left it there, come back the next day, flipped something, turned something on and suddenly an idea comes from there and I don’t remember how that was. That happens a lot with me. I might be working with something and turn it around the next day, so yeah, I’m kind of as in the dark as you are. A long answer to the short questions.

DS: Sometimes it sounds like an accident.

WE: Yeah, those are the great bits. Anytime I think I’ve had an idea I think is going to work, it’s always a disappointment. The good ones often seems to be an idea that don’t get through, but something that gets hatched, that we haven’t anticipated. It’s the side that’s the least reliable part of the process because you don’t know when it’s going to happen, but you have to hope that it will and that you’ll be aware of it. If I sit down and play the piano I just do a certain thing, but when I get into this terrain with instruments that I don’t really know, or when I don’t know what I’m doing with the loop stations and the synthesizers, that’s when I start finding things. Having long days of playing, you notice these things happen where you play worse and worse until you play like shit – and then something happens.

DS: Could you just talk quickly about your relationship to movies.

DS: Could you just talk quickly about your relationship to movies.

WE: The most recent soundtrack that totally blew my mind was Under the Skin. Every level, also visually, is just so amazing and the music is fabulous for that film. It’s so great to see things that challenge your perceptions and that has some confidence in the viewer, which is also why I like Lars von Trier. He’s always throwing something different out for us to look at, always trying to do something with the language of cinema. Also really like Gaspar Noé’s films a lot, I loved Enter the Void which was a perfect film in many ways. Again, a film that has this kind of instinct of film language and where the film is the sum of all its parts, that’s my kind of dream films – like the way Kubrick paid attention to sound in his films. One of my favorite film soundtracks is Aguirre by Werner Herzog, because the counterpoint between the music and the images is breathtaking. It’s out of this world, that one. I watch a lot of films and I love David Lynch for those reasons, too. I liked Drive a lot and Valhalla Rising. I liked Inherent Vice, too. I had no fucking idea what it was about, I was so confused. Again, it didn’t treat the audience as morons. Gravity was also a cinematic experience. It was the first time I tried 3D and for two hours you were in outer space. It’s what you want from a big blockbuster. I went and saw that twice. Like bang-bang. The same with Under the Skin, the next day I went back and saw that again.

I mainly go to the cinema to get sucked into it and I don’t want to just watch a film. For me it’s a moment that’s very special.