An epiphany

Silence! Be quiet! Because listening is active, because the birds have already left but their sound still reverberates. Silent all ears that listen, stunned by the noise that is gone but still relishes. The soundtrack? Our life! That one of changes, transition, mutation and mysteries, that one able to peer into the recesses of the deepest realities, responsible for questioning the apparent manifestations of the abstract and the concrete to go into unexpected territories of consciousness. These are the realities of sound phenomena, the challenges of searching for a continuous vibration, a pure sonic experience.

Let the mind travel around 2.500 years ago: we’re here in the Pythagorean School, waiting for the teacher to lead us into the most unlikely truths of the cosmic harmony. Our eyes are eager, the heart rumbles and a curtain, the veil of listening, can be seen on the horizon. Suddenly, a voice is heard, the teaching begins. The eyes, yet expectant, cry for the face of the talking master, who is not (and will not) on the retina. The curtain is still there and is the only visual reference for the sounds being heard. The voices possibly emerge from the cloisters of the mind or perhaps from the same shadows in the curtain, where the teacher continues his mission.

Silence! Be quiet! Because the sound is active, the akousma has emerged and the sonic code is already running through the mazes of the passions and the cusps of thinking. Slowly and without seeing, the oral reality becomes symphony, opening the doors to an intimate universe, the acousmatic. The teaching behind the curtain now makes sense and invisibility brings a message to the cochlea that is impatient because of its blindness. Over time it gets calmed, the world of sound is clear and the government of tongue and thought becomes possible, and with them also the desires and the scars of those memories that despite of being absent, still hit the listener’s soul.

And so, behind the curtain, sitting in silence, the initiation begins.

The acousmatic listening

“In ancient times, the apparatus was a curtain; today, it is the radio and the methods of reproduction, with the whole set of electro-acoustic transformations, that place us, modern listeners to an invisible voice, under similar circumstances.” – Pierre Schaeffer, Treatise on musical objects

The word “akousma” has its origins in the greek language; a word that is a mystery on itself and has a lot of stuff to teach; yet on its basic form, denotes the act of listening, or the moment of audible perception, suggesting no other distractions, such as the visual. That term had a big importance in the school of Pythagoras in the Ancient Greece because he used to teach acousmatically, behind a curtain, only caring for the sound itself and inviting to “just listen”, in silence.

That was present mostly in a context of semantic teaching, an exploration of the message present in the sound without being distracted or influenced by other perceptions. In the middle of the past century, the French genius Pierre Schaeffer, used the “acousmatic” term for his research into music and sound. The starting point of his exploration was to find the state of acousmatic sounds, that is, behind the curtain, without the visual stimulus.

Schaeffer’s exploration, however, was not limited to just closing the eyes. He also tried to theorize and justify the basis for what was initially called musique concrète, then became acousmatic music, and today is maybe simply understood as acousmatic sound or acousmatic experience, in which sounds are an open and undiscovered reality of their own. In his magnum opus, the “Treatise of Musical Objects”, Schaeffer realized about the importance of the listening modes when defining and understanding sound itself, besides having devised a way for theoretically organizing sounds in different species and categories, based on the idea of sound objects, which is the result of one of his most important research findings: reduced listening, the act of looking for sound in its own sonic world.

What we know as acousmatic sound is nothing more than the sound in the universe of mere sound. Reduced listening leads to a conception of sound reality in the territory of pure sound, which is not linked to physical causes that produce it, nor contains the semantic content or visual elements related to it, nor even the tools from which sounds are played (such as a computer, a speaker, etc). The reality of sound itself is a reality of sound-objects or sonic imaginative structures, of just sounds. It’s a exploratory space of the sound image in its pure state, in which are evident its own morphological characteristics and qualities.

“The acousmatic situation changes the way we hear. By isolating the sound from the “audiovisual complex” to which it initially belonged, it creates favorable conditions for reduced listening which concentrates on the sound for its own sake, as sound object, independently of its causes or its meaning (although reduced listening can also take place, but with greater difficulty, in a direct listening situation).” – Michel Chion

Since the beginning of the acousmatic movement in the Pythagorean School, there’s a persistent question around the fact that any sound image is altered depending on the way we listen. Depending on the way we consciously process the sonic phenomena, the sound that is created in the mind, changes dramatically. Listening modes affect not only our perception of sound materials, but also expand the possibilities of it, its scope both in our mind as when we’re trying to transform sonic pieces, fix them in time or combine them in diverse ways.

In short, listening is the main responsible for this “acousmatic state” of sound. Listening is the only way to know, to investigate or think of sound as such. There’s no sound object if there’s no listening that leads to it. And if we go further, in sound design, there would be no sound effect without having such object of perception at the first place.

A universe of mere sound

Sound objects are silent silhouettes floating in an ocean of memories. They are nothing but perceived sounds, raw materials, shapes of listened phenomena, already out of their physical realm. That characteristic is what makes it possible to be creative in terms of the images we’re able to evoque with them. Actually, we could think that a discipline such as sound design, takes its essence from that perspective, since the fact of not having any kind of fixed contexts to the sounds we capture, makes it possible to give different contexts to those elements and to give birth to what’s often called “cinema for the ear”.

“Far from simply isolating the ear and offering a privileged glimpse into the essence of listening, the acousmatic listener continually attempts to use the knowledge he or she has garnered from fellow senses to make sense of his or her auditory experience. […] Acousmaticity, the determination or degree of spacing between source, cause, and effect, depends on the cognitive state of the listener and the knowledge they possess about the sound heard, its environmental situation, and its means of production, among other factors.” – Brian Kane

In the acoustic field, there can be a difference between the sounds we could imagine and the sounds that are in fact vibrating in the air. But, in the universe of listening itself, there’s only universes of sound, not acoustic in the strict sense, but acousmatic. That means there are no acoustic causes at certain point of perception; there’s no solid, or liquid or gaseous, there’s just the sonic. In the acousmatic universe, the object is already “bracketed”, isolated on its own field, placed on his own perceptive domain, detached from any causality or reference; completely given to the imagination.

That universe is the home of a sound designer and his/her work is pretty much the act of going back and forth between the acoustic/causal and the acousmatic/non-referential worlds, between the symbolic/semantic/contextual territories and those essential, sonically reduced or “acousmatized”. The sound designer has a privileged position because his/her role is able to get into different modes of listening in order to establish different contexts and meanings towards the material he/she creates; as said before: the way of listening is actually radical for designing sounds because the listening perspectives shape the notion behind the sonic phenomenon itself, thus creating new contexts and appreciations, similar to what happens in music.

“In acousmatic music, one may recognize the sound sources, but one also notices that they are out of their usual context. In the acousmatic approach, the listener is expected to reconstruct an explanation for a series of sound events, even if this explanation is provisional. Like reading a detective story, one invents a scenario to find the chain of causality that explains the situation.” – François Bayle

Sound design starts naturally as an art of listening and then comes to the fixed images, at least at its fundamental state. The greatest sound scenes created in visual or non-visual media are mostly the result of a particular way of listening, and many times, because of the acousmatic contract, as a result of the dialogue between sounds that are just sounds and sounds that could mean something. An iconic sound effect is not necessarily complex in terms of technical aspects or its difficulty to be made, processed, layered or designed. It’s just a special sound that is found by the creativity of relating the acousmatic properties of the sound and re-contextualizing it in new ways, as the gestalt process over listening.

Let me explain: the acousmatic process evolves into what’s called reduced listening, a method in which sound is detached from any non-sonic context, getting bracketed in its own realm, isolated of any other universe. There, the acousmatic process is not just a mere way of conceiving sound, but actually an activity, an exercise. That is perhaps the most brilliant aspect of what Schaeffer started: not just a prolific theory and a liberation of musical perspectives, but an invitation, a practice, a way of leading us to focus on listening. That’s how the concrete music proposed it and how its advocates defined it. As Brian Kane states in his recent book “Sound Unseen”, “Schaeffer understood the acousmatic reduction as more than simply a theoretical prescription to withhold presuppositions. Rather, it promoted an art of listening”, an aspect that is truly important because it opens the way to the real acousmatic experience, the perception of sound directly, and forces the student to listen, as Kane says, “it must be heard.”

That exercise has a big potential on the acousmatic point of view listening in a film. That is when designing sounds that would be placed in spaces which are not necessarily dependent on what’s visually happening in a particular moment. Nondiegetic or unseen sounds that could appear in the story have big possibilities in terms of storytelling and imagination because they often rely on that mystery of the acousmatic presences, the unknown sounds, noises that are not present to other senses, not dependent on causes different than the sonic; although in situations such as a film, the usual axis would be the story itself, and the question here would be both about the possibilities of sound by themselves and not always dependent on what is being watched, but also on how the contrast with the visual information could be established.

“When a sound cannot be identified, for however long, we normally are compelled to find out what is the source. Perhaps if it seems innocuous, weak or doesn’t repeat itself, we may not give much attention and ignore it. But if there is any power to the sound in either reduced listening (e.g. loud, sharp attack, repeated) or semantic listening (e.g. scary, funny, oddly familiar), then our conscious minds can barely resist being drawn into the quest of source with causal listening. It serves as a catalyst for problem solving, shifting complacent energy into action. The speed of moving from unknown to known may also be influenced by culture, education and exposure to similar kinds of sounds.” – David Sonnenschein

Also, in that point in which sounds are nothing else but sounds, in the actual practice and perception, the sound designer finds another creative possibility, by being allowed to give another context to any element, actually going into the ambiguity of the sonic images and its relationship with other aspects: narrative, emotional, visual, evocative, imaginative, symbolic, etc.

As said, in the acousmatic sense, the sound object is not dependent on the causes, is not related to anything we could find in the common material world. That state of the sonic matter allows to not only listen to the sound as just sound, but to give it a new context, which is what happens all the time in sound design: the lightsaber sounds like a lightsaber, not as its cause: a signal interference; horse walks sound like horse walks even when foley artists create them with coconuts. There are spaceships created with toys, sci-fi sounds made from toilets or dramatic room tones built in rooms that are not necessarily the ones that are seen in the film.

If sounds wouldn’t have its own realm, those illusions would be imposible to create. And there could be thousands and thousands of examples of this. In the art of foley for instance, there are a lot of creative examples of different resourses and objects that are not valued because of their qualities in the physical world, but their richness in terms of the acousmatic spheres, the morphological qualities and its properties as raw materials, which potentially affect the notion and creation of texture, form, and of course, space, which is actually deeply affected by that acousmatic relationship.

Invisible listening, an invitation

Sound designers are permanently crossing the frontiers of the mentioned fields because sounds are not attached to other references and the microphones (fortunately) doesn’t capture visual images, descriptions or thoughts. What if when capturing sounds in the field we could capture the context, the visual image? The possibilities would be very different.

That’s why it is so important that we actually get into listening to the sonic universe in the acousmatic position, being able to detach ourselves of listening to sounds of visual environments in order to get into only sonic territories. It’s a constant exercise that doesn’t needs to be positioned in the place of other critical, analytical or contextual modes of listening, but can be found as a unique way of relating with sound and complementing the other sonic process and listening methodologies that humans are capable of.

Also, it’s just done by closing the eyes (which is really a great practice, as Doron pointed in his last article), because actually it can be done with the eyes opened, although it’s more challenging in some ways, at lest for people who is not searching for sound them majority of time. This practice is really about understanding the different relationships between the senses and particularly the way the sonic phenomena arises from the relationship between the causal realm and the territory of pure perception. In other words, it’s a way of expanding the possibilities of sounds inside ourselves, and with that the act of being conscious of our own sonic realities.

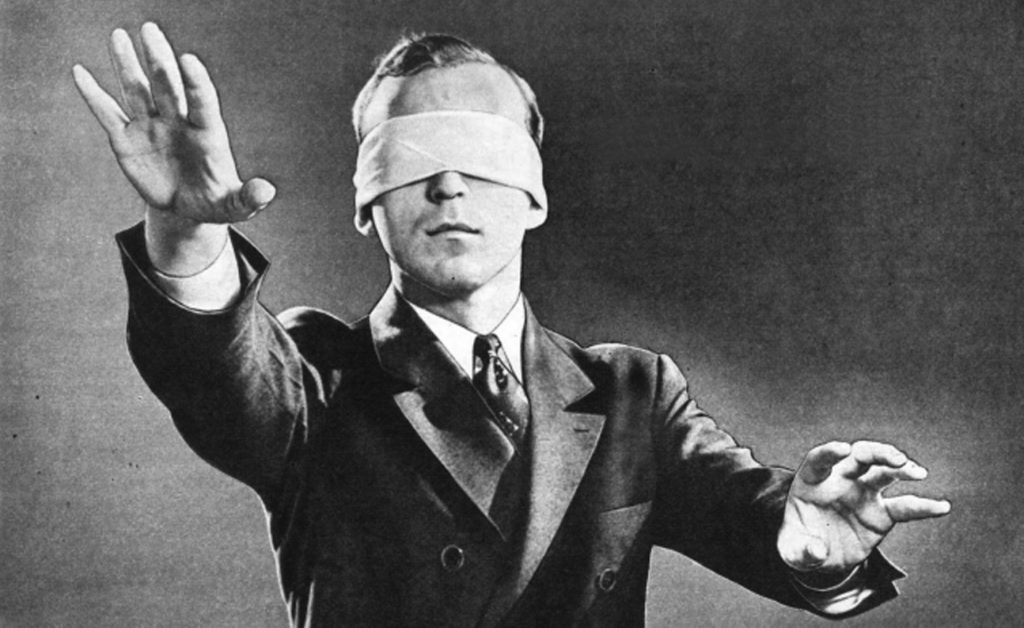

“The acousmatic is an action of focusing on sound, on reducing its context not in order not to see its source but to rethink the context which names and values the source as one actual object when it is a plurality of things thinging. […] The term acousmatic then is predicative; it is a sensory-motor action toward the world blindfolded: plunging the world and the self into darkness and walking toward each other. It means to do an acousmatic exploration”. – Salomé Voegelin

Just as sound design opens the way for the sound-object to come back to other territories but sharing new faces and contexts, at the same time, the sound designer’s role deeply affects the way we connect to the world, because when closing the eyes (or just reducing the importance of the visual/causal) in order to hide the visual stimuli from our experience of reality, we allow ourselves to go beyond the boundaries of perception and start creating the contexts in the moment of listening or recording itself, which then are translated into new relationships at the moment of editing/designing/mixing.

Of course, many times it would be different than composing for sound pieces that are acousmatically intended and will listened in environments actually conditioned for that, because here sound would be usually returned to non-acousmatic contexts, such as some aspects of the story of a film, the visual elements of a scene or the concepts of a game, which are the “design” aspect of the role. But here, let’s just focus on the invitation to the activity of listening and the act of composing sounds from this acousmatic state, because at some point, sound is itself telling the story, not dependent on other aspects and even in visually-guided cues, environments, movements, characters or emotions, there could be always an acousmatic exercise in which the sound designer is constantly challenged to find new relationships between the raw sonic materials and its evocative features.

Just from sound, the possibilities are infinite because imagination is infinite, and actually there are so much aspects of the sound design workflow that makes the acousmatic search a very interesting one: when listening, when recording in the field, when organizing a library, when searching on it; the fact of being able to transform sounds, to shape them, to spectrally analyze them, to chop and reunite them, to reverse, time-stretch or repeat them. Those are impressive opportunities for exploring listening and looking for the shapes and details of sounds on its own world.

The act of listening and recording sound effects or capturing potential material for working on sound design is actually a process where the artist finds its activity as that one of the illusionist of sound, a harlequin of time, storyteller of the unknown. There are tons and tons of examples of that, and the creativity of a sound designer is actually found in that way of giving new contexts, meanings and aspects to any sound present in the world. But, as always, the best examples are those that you can identify, so all this comes to the point of inviting you to the process.

Tools are important; plugins, effect processors, samplers, crazy instruments and controllers; that’s ok, but all of that is nothing if we don’t train our ears first, because inside them where all the magic actually happens. And by training I mean not only to be physically disposed to listening, but also mentally, perceptually, spiritually if you like. It’s not a process of mere listening to whatever could be possible, but a way of connecting to sound, of expanding our imagination from what is going on in the sonic universe. There’s no much science on this theoretical silence, and no matter how much we care about describing the process, the real deal is inside the practice.

So… Silence! Be quiet! Because imagination is active and the possibilities are endless, because listening has its own reality and it’s only a task of the ears to conquer it.