“One can look at seeing but one can’t hear hearing” – Marcel Duchamp

As you may know, silence is the topic chosen for this month here at Designing Sound. One may think silence is not existent if we value it as an absolute sonic absence, but here I’m going to examine its role and possibility towards the act of listening to sound, silencing, not as that state of complete sonic deletion but as a force able of letting sound to be. Here’s not about asking “what is silence?” but just creating an invitation to be silent and just listen.

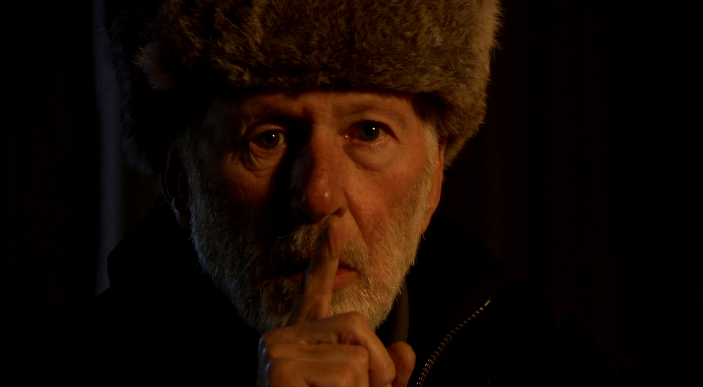

A silent voice

“Silence is not the absence of sound but the beginning of listening. This is listening as a generative process not of noises external to me, but from inside, from the body, where my subjectivity is at the centre of the sound production, audible to myself. Silence reveals to me my own sounds: my head, my stomach, my body becomes their conductor.” – Salomé Voegelin

I think silence is found in sound itself, not outside of it and not as an opposite of vibration, but on its direct possibility, the condition where all sounds are already happening. As John Cage said, “silence is not acoustic, is a state of the mind, a turning around”. That turning around is openness and liberation towards hearing, a connection to what’s already sounding. Silence here means a spiritual connection to sound, shapes the soul of listening, its endless space. It makes listening possible also making it a careful and conscious activity.

I like to value silence as an activity, as a verb, not an object, not “something”, not a word even, but a process or experience that leads to anything. A good friend of mine once said to me: “silence is the best sound you can listen to”. And over the years, that premise has been teaching me a lot of things, primarily the fact that what we listen to is not a sonic sound, but a sonic silence, a vast universe of silent forms we call sounds.

Sound, silence, both faces of one same coin. They’re one and need each other to exist. We can not value them separately because they’re always creating one single phenomenon. Sound is only possible in the present moment and the present moment is silent in the listener’s mind. Sounds are constantly silent, constantly passing by, constantly dying as they live. They don’t stay because staying is not something sounds like to do, they simply can’t.

“Sound is absence, beguiling; out of sight; out of reach. What made the sound? Who is there? Sound is void, fear, wonder. Listening, as if to the dead, like a medium who deals only in history and what is lost, the ear attunes itself to distant signals, eavesdropping on ghosts and their chatter. (…) Sound is a present absence; silence is an absent present. Or perhaps the reverse is better: sound is an absent presence; silence is a present absence?” – David Toop

Quietly listened sound

Any sound, if you think about it, always comes from silence and leaves in silence. We can never really see a sound, name a sound or catch a sound, because in order “to sound”, a sound needs to die, needs the silence, its ghostly essence; as any vibratory activity in our life, it is transitory and ephemeral, always moving over what’s eternal, that quiet and open territory, that sound of listening, that act of being.

For instance, if we try to listen to listening, it’s like trying to listen to silence, which is actually trying to capture the nature of sound, which is not sonic but silent in our mind.

“Common sense would have it that somebody listening doesn’t make any sound; or else, if he (sic) does, it is not only secondary (leaning over, for example, or moving around) and not as a listener. Listening as such is thus silent, it cannot be heard.” – Peter Szendy

Listen by David New, National Film Board of Canada

In various philosophical traditions, there has been a deep study of the sonic phenomenon based in the study of the act of listening as a universal silent activity. Not silent because of being “not-sonic”, but the contrary: so silent that allows to listen to all the sound. “To listen” is here “to make silence”, “keep silent”, “remain silent”, which leads to a deep state of awareness to sound, a state of attentive listening.

The best method for understanding sound and connecting deeply to it is by keeping silence. It’s the true way of listening, by silencing any activity in order to deeply feel the unstoppable emergence of the sonic manifestation. All sounds happen in silence, always transiting over that infinite space.

And I’m not talking about going to the mountains or taking refugee in a silent natural place or something like that, although that kind of environments is always great for many people. I’m talking about doing silence as a way of connecting with sound, any sound… When walking, when working, when living. In any moment, any place, there’s the possibility of being silent, not as “killing sound”, but actually as an attitude towards what’s already living and happening in the auditory realm, in the vibratory layer of everything; the quiet presence of listening in a world full of sound.

Silence and field recording

“My ear, still very much a part of me, became an extension into and through the environment itself. A wandering membrane, equipped with its own feet – ones that allowed me to move beyond my own immediate and confined position, and back again. At last I had found a walking that resonated with me: personally, politically and situationally. It was not in freedom or pleasure, defiance or counter-strategy, but in the pain and restriction of my own experience.” – Mark Peter Wright

Being silent is not to be isolated from the world but connected to it in a new way. It’s a method of realizing our connection to everything, a deep consciousness of the environment and everything that inhabits it. Since ancient times, silence has been even a profound way of connecting to the universe itself, a contemplative activity that makes us aware of all those things we are used to ignore. Quoting Cage again, silence is an experience, “a religious spirit in which one feels there is nothing to which one is not related”.

When it comes to meeting with the soundscape around us, there’s an activity many of us practice: field recording. That process besides of having a lot of technical and rational elements, is an activity that not only let us register some sounds, but invite us to silence, allowing us to listen attentively, whether doing soundwalks or listening quietly and still in any spot. That’s probably one of the most direct ways we sound makers have to explore inside the environment, perhaps one of the most active processes we have at hand, and we even have the opportunity of reproducing the captured material in the studio and deeply analyze it and study it, in silence.

Silent listening can be practiced, doing a very basic thing, as “simple” as not talking and getting out from the inner noises. That’s why recording in the field is a meditation towards sound and becomes an expansion of senses. It’s not about the recorder really, but our ears, our body and the resonance that happens within the sound and the listener, which in silence, are the same.

One of the most fascinating activities a sound designer does is field recording, but more fascinating than that, is what occurs when recording. To go out to discover sounds and imagine other sounds being made from those we aim to record, to find interesting and challenging places to be and record, etc. It’s an intense way of attention to the sonic phenomena; although, the special point here is not just the sound we capture, but the sound we make and how we interact with the environment.

Field recording (and specially ambience recording, in my opinion), invites to deep silence, to meditate in the moment, to completely feel the sound. It forces us to stop, to silent our voices and be quite present in the audible realm. It’s a process that leads our minds to new ways of connecting to sound and although there’s of course a technical process going on and there are a lot of thoughts happening while recording in the field, the real process is the silent one. As Salomé Voegelin says, “silence is possibly the most lucid moment of one’s experiential production of sound.”

An exercise of emptiness

“If we have a hope of improving the acoustic design of the world, it will be realizable only after the recovery of silence as a positive state in our lives. Still the noise in the mind: that is the first task–then everything else will follow in time” – R. Murray Schafer

Silence is the exercise of being, an act of detention, of contemplation; it’s the interest for listening. The real sound is found in the deep silence of the mind because what is really happening is silence, always. Sounds as particular things are always coming and leaving, but there’s a nature on them that plays the role of the only constant, and it is that silence, that ephemeral essence of vibration.

Today’s world needs silence because it needs listening. We’re facing crucial times regarding sound so we urgently need to listen; to keep silence and be aware of what’s the world saying inside/outside us. At the end it’s just about one world, one single sonic universe in which we all inter-connect all the time and in which we all have a responsibility for being conscious and attentive. Not only our work benefits from that, because first of all, we need it, the earth needs it, our minds also; we all need the peace of silence instead of the fear of it.

“Conversely, if I were to hazard a definition of silence I would describe it as the particular equilibrium of sound and quiet that catalyzes our powers of perception. […] What’s unknown, then, is the world around us; what’s missing is our awareness that we do not know. Silence as a state of expectancy, a species of attention, is a key back into the garden of innocence.” – George Prochnik

So, in short: to be silent is not to “not be sounding”, but being conscious of any sound. And to be conscious of it is not necessarily to think, name and conceptualize it, but the contrary: to be as quiet as possible, until the mind starts to get out of unnecessary judgements, where sound is freely listened on its implicated equanimity. There, it’s just about listening to nothing in order to find the sound of everything. We can develop that sense and train our lives for that; the consequences are abysmal.

After all, there’s no sound “outside” us because all is sound and we ourselves are it. There’s always sound and there’s always the silence that opens space for that sound to be experienced. That is very easy to say but in practice is where it gets into the real point. Silence can not be defined, can not be caught, can not “be” without sound. It’s a mental exercise, a peaceful dose of nature, the activity of being quiet and aware.

If we keep the silence, we find the sound.

thank you

Yes, thank you indeed.

As field recordist the most enjoyable part, by far, is not the hunt for interesting sounds; not taking home a flash card full of great recordings – but THAT exact state you are talking about.

When the “tape” is rolling and I just sit there, listening, trying not to breathe loudly or move at all, disappearing into the moment completely.

In that moment, I am calm, because I have to. The nature of the work forces me to be calm. There are no more dials to dial, buttons to press or mics to position – all that is done. But I also can’t let my mind wander too much – or I will lose that calm and perhaps even make a noise by accident. Which is another plus. In order to do the work right, I need to stay in that meditative state for as long as I’m recording. Nothing like spending a few hours like that.