It’s still Paul Davies’ month here at Designing Sound and now is the time to dig into one of Paul’s most celebrated works: Hunger.

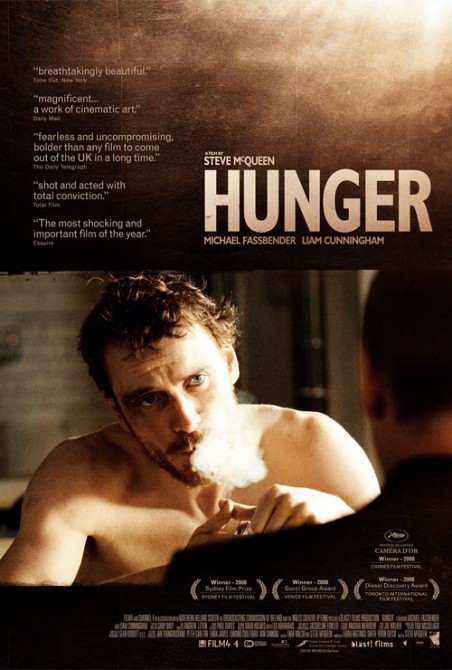

This 2008 film tells the story of the fierce battle between the Irish Republican Army and the British state, which in 1981 led to a hunger strike in which 10 IRA prisoners died. A haunting, intense drama that has received worldwide acclaim – it premiered at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, winning the prestigious Camera d’Or award for first-time filmmakers. It was also a major breakthrough for the lead star, Michael Fassbender. Paul Davies talks about the film’s extraordinary stark soundtrack:

Designing Sound: How did you get involved in Hunger?

Paul Davies: My initial contact for the film was the producer Laura Hastings-Smith, who I’d worked with before, on a film called The Lives of the Saints, directed by Rankin, the well-known British photographer. Laura, because of my work on this film, suggested me and Richard Davey (who had been the re-recording mixer on Rankin’s film) as the sound team for Hunger. I went for a meeting with Steve, which went well, and subsequently we were appointed as the sound post team for the project.

DS: The director Steve McQueen has a background in video art. How did that influence his filmmaking, particularly the use of sound?

PD: As you say Steve has a background in film and visual art, however my relationship with him was no different than with any of the other directors I have worked with in the past. Steve related to me as a narrative filmmaker, and not as a fine artist. The only time I was really aware of Steve’s fine art background was in our initial meeting which happened before the film had been shot and he showed me his visual reference book, which contained images of renaissance paintings and contemporary photographs from the period of the hunger strike. After this Steve’s concerns were with narrative and atmosphere, and how we were going to convey the emotion of the story in sound and images.

DS: How was your working process and your schedule on the project?

PD: As I indicated in the earlier section I had read the script and had a meeting with Steve about the conceptual approach before filming began. After this, because the film was actually shot in two sections three months apart, to allow Michael Fassbender the lead actor to lose weight, I saw a cut of the first two thirds of the film, before the second shoot and then saw a couple of versions of the complete film before starting work on the sound design with my assistant sound designer Chu-Li Shewring.

The sound post process started with a detailed spotting session with Steve and the picture editor Joe Walker, Joe had also compiled his own sound notes which acted as a basis for the sound design. Already from the cutting copy Steve and Joe’s intentions regarding the minimal use of music and the use of production sound effects recorded by Mervyn Moore the location sound recordist, provided a clear template for us to follow. The actual time we had for sound editing was actually quite short, four weeks each for me, Chu Li and Peter Shaw the dialogue editor. Fortunately Mervyns’ tracks were very well recorded and provided a firm foundation for us to build the sound design upon and also meant that we only had to record minimal ADR. Tim Alban recorded and edited the foley, which also provided a crucial element in the sound design. We knew that much in the way we had worked on Lynne Ramsay’s films we would want to be able to foreground well recorded Foley in the mix so as to “zoom” in to the characters in the film, to draw closer to them and feel their physical presence.

DS: Dramaturgically, it’s a very interesting movie. The film focuses on different characters throughout the film and the first half feels very realistic whereas the last part is often very subjective. How did this influence the sound design?

PD: Steve was very clear in our first meeting after we started on the sound editing that he didn’t want a conventional prison film i.e. all slamming doors and keys in locks and a busy crowd track shouting throughout in the background. I had laid up some initial tracks of “typical” prison atmospheres, Steve came in and listened to this and said that this was precisely what he didn’t want. We then started discussing the conceptual approach that he wanted for the film, he mentioned the work of the French director Robert Bresson, and his film A Man Escaped in particular. I hadn’t actually seem this film, and it wasn’t available on DVD in the UK at the time, but I was familiar with Bresson’s work from Film School and my involvement with Lynne Ramsay, and I had also read his excellent book on film making (which is essential reading for all film practitioners) “Notes on Cinematography”.

So I knew from all this that we would be adopting a very spare sound style, focussing on one thing at a time, in a very controlled and precise way. So although the film may seem “realistic” on the surface, it is actually quite stylised underneath, and you are right about the change in the final third, this was a conscious decision I made that as Bobby is moving closer to death the atmospheres changes and there is even the subtle inclusion of electronic sound design elements. From the way this final third was shot, it felt to me that Bobby was already in the ante room of the afterlife as it were, and so the sound becomes more esoteric, nebulous and floating.

DS: There’s a lot of extremely intense sequences with Bobby Sands at the end where you really feel the starvation he’s going through. How did you work with the sound to get close to Bobby? Did Michael Fassbender do a lot of breathing ADR? And did you go through a lot of passes to create something like the imagined childhood dreamscapes?

PD: We used foley as a device to draw us closer to the characters as mentioned earlier, focusing on small movements etc. But I had also decided fairly early on that we would need to bring in Michael Fassbender to the ADR studio to record breaths. Normally on most films, breaths are re-recorded just to cover a few scenes, if at all. However on Hunger we spent about 3 hours in the ADR studio with Michael covering breaths pretty much throughout his scenes in the film. This again has the effect of pulling in the viewer closer to the character. It was important to get the original actor to record these breaths by the way, as the performance of these breaths was just as important as any scripted ADR, this was a point that Michael understood straight away, and he gave his full commitment to the process. It was also the reason why I supervised all the ADR recording for the film, as I knew that it would be a vital component of the sound design, we recorded breaths for the other main characters in the film as well.

DS: There’s an impressive use of dynamics and often some quite hard cuts between scenes throughout. Was this something you developed in the sound editing or was it more of a mix thing?

A: This was something that we developed during the sound editing process, and the was further refined during the mixing stage with Richard Davey, the re-recording mixer who did a good job of creating such a precise yet emotionally powerful mix.

DS: How much effects recording did you do? How big a factor was realism for you – did you use the factual sounds for the prison and cars etc.?

PD: Unfortunately, because of the tightness of the sound editing schedule we had no time to record bespoke sound effects for the film, however very kindly a French colleague Vincent Hazard gave me access to a library of sound effects that he had recorded in prisons and hospitals and these proved invaluable in constructing the unique atmosphere of the film.

DS: Did you research a lot to find the proper sounds and props for the foley? The baton banging on the plastic shields is one particular sound that comes to mind.

PD: Again lack of time was a restriction in this regard, and in fact the baton and shield banging is pretty much all original location sound built up and layered.

DS: What’s your own favorite sequence of the movie?

PD: The sequence of Bobby dying in the hospital bed being visited by his mother and then the bearded man, the subtle stylisation of the sound design creates a very powerful effect, especially as this is something new in the film, a technique which we hadn’t used previously – it was more effective when it was introduced as a new element. The sound here becomes very interior, it is all from Michael’s point of view, we see the bearded man speaking, but the sound of his dialogue is very muffled and unintelligible.

DS: I read an interview with Steve McQueen where he said: “Sound, for me, was the most important part of the film because it fills the spaces where the camera just can’t go. A sound can give you the dimensions of a room. It can give you smell, it can give you tension. In some ways sound can travel itself into other areas of our senses, other areas of our psyche that unfortunately cannot be just viewed.” How did these thoughts influence your collaboration?

PD: Steve made it clear right from our first meeting that the sound would really form 50% of the impact of this film. Steve had a very clear concept in this respect. I think that part of the reason that people have always commented on the sound in Hunger is that because there is very little scored music in the film so the focus of the audience is naturally drawn to the sound design, and because the soundtrack is so stark and each sound so carefully chosen it resonates in the viewer’s mind.

Great stuff!!

another great article for me to wake up to

Really great article. Great that McQueen appreciates and respects the sound so much, I am realising that more directors are paying closer attention to sound, but the McQueen quote mirrors what I say to people when talking about sound design and I concur fully, even more of legend in my eyes now.

I’m going to watch this film again with this knowledge in mind.

Thanks for sharing

Graham Donnelly