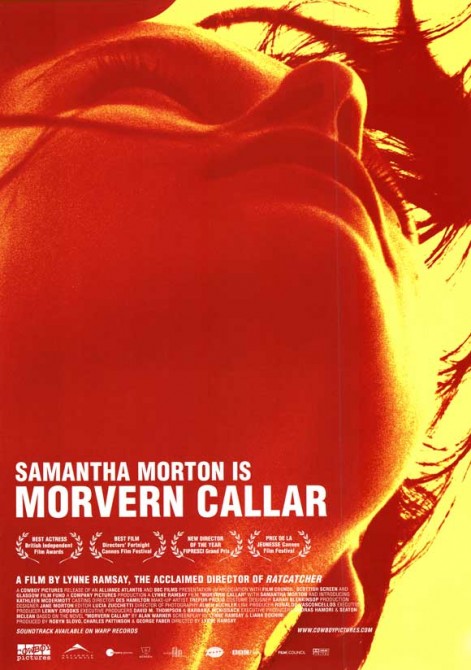

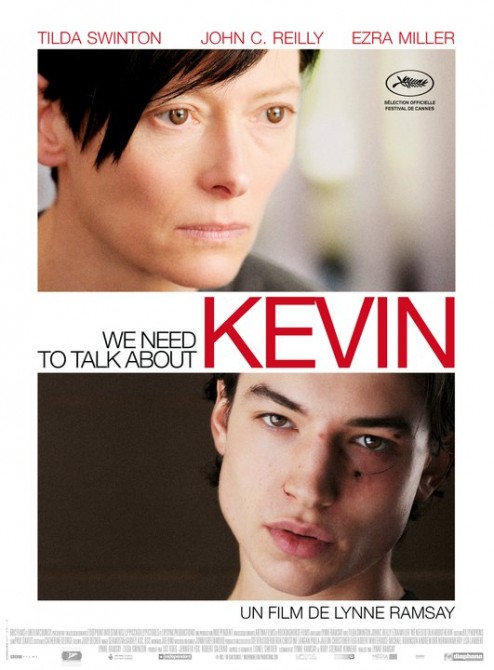

It’s time for the next part of this month’s Paul Davies special. One of Paul’s most prolific collaborations is his work with Scottish director Lynne Ramsay, best known for her feature films Ratcatcher, Morvern Callar and We Need to Talk about Kevin, which have all been highly acclaimed. We Need to Talk about Kevin premiered at this year’s Cannes Festival and is released in the UK next month. This interview focuses on their special working methods and close creative kinship.

Designing Sound: How did you and Lynne Ramsay meet the first time?

Paul Davies: I first met Lynne when she was a student at the National Film and Television school in Beaconsfield, UK. I had already graduated, and was temporarily working in the sound department as an assistant to the Head of Sound, Gareth Haywood. Lynne was a camera student at the time, and I remember her being a regular visitor to the sound office to discuss filmmaking with Gareth, especially their shared love of Robert Bresson and Tarkovsky. However, I only really got to know Lynne well, some years later when I worked with her for the first time on Ratcatcher.

DS: How would you describe her as a collaborator and filmmaker?

PD: Lynne and I have developed a very close working relationship, and she has in fact become a good friend. We begin discussing projects a long time in advance of filming, and I receive early drafts of the scripts, and our collaboration progresses from there. With each film the working relationship becomes closer, for example I have already produced a sound sketch for one of Lynne’s proposed next projects, and I have seen a treatment of another, for which we are discussing the overall sound approach. Lynne is by nature very collaborative, and she always ensures that she leaves enough space for other to contribute while being very clear in her direction and conceptual input.

I should also mention the importance of Lynne’s other collaborators in post-production and their contribution of ideas and concepts Lucia Zucchetti and Pani Ahmadi-Moore the picture editor and 1st assistant from the first two features and all the shorts, Richard Flynn sound recordist and dialogue editor, and Tim Alban, re-recording mixer on the first two features also, Joe Bini and Adam Biskupski, editor and 1st assistant on We Need To Talk About Kevin, alongside Simon Changer and Robert Farr, music editor and re-recording mixer respectively. All were essential collaborators on these soundtracks, with everybody encouraged by Lynne to make their contribution. She is very good at building a collaborative, collegiate atmosphere on her films whilst at the same time being decisive when presented with choices in the mix, a very good combination to work with indeed.

DS: You’ve now collaborated on three feature films. Quite often, sound can be very tricky to talk about – how do you communicate about sound and how has your dialogue evolved throughout the years?

PD: Yes, sound is notoriously difficult to discuss with directors, but Lynne has a good ear for sound and is a musician herself, and over time we seem to have had little difficulty in discussing sound concepts and ideas. It certainly helps when I am able, as I was on the last film We Need To Talk About Kevin, to begin work early on in the process, as the picture is still being edited, this meant that I was able to submit work in progress, so that Lynne, Joe Bini and myself had something concrete to discuss and a basis for development of the soundtrack, and we were quickly able to see what was working and what wasn’t. However, by this time I am very familiar with Lynne’s tastes and generally know what works for her and what won’t. That being said

Lynne is always looking to progress as a director and in her film making language and techniques, so it’ s never a case of offering up what worked before, but always seeking to move on.

DS: I remember the two of you discussing your methods at the School of Sound in London in 2005. Here you mentioned that on Morvern Callar you reversed the creative process somewhat and started out with sound editing before picture editing. Could you share a bit of light on this process – pros and cons?

PD: On Morvern, this was actually more an aspiration than a reality. However, because the book featured music that Lynne was unfamiliar with I did compile a CD-R from many of the tracks mentioned in the book from my own record and CD collection, and this was very helpful to Lynne and Lucia Zucchetti while they started editing the film. It was our intention to produce a “sound storyboard” before shooting began on the film, but time and circumstances conspired against us. However, I feel that with Lynne’s new proposed projects were are moving nearer to the ambition of having sound sketched out before shooting, and it certainly helps having sound design and editing software available on a laptop rather than on an expensive cumbersome DAW that was the case 10 years ago with Morvern, so sound design can be produced much more easily and flexibly. I think the advantage of working on the sound early is that it helps the visuals and aids in the picture editing of the film, whilst providing a clear idea of the sound style of the film, also bringing that which sound conveys so easily, an emotion and feeling, giving an indication of the mood and atmosphere of the project.

DS: Did the process differ on Ramsay’s latest film, We Need to Talk about Kevin? And how early on were you involved in the film?

PD: As I’ve already mentioned, although we didn’t produce an audio storyboard, I did begin work on the film before director’s cut was completed, this is far earlier than I had begun work on either of Lynne’s previous films, and therefore I feel we were able to push the sound track further and explore creative directions which we hadn’t been able to with either of her two earlier films, because of their tight schedules.

DS: Lynne Ramsay’s films are often extremely dependent on sound for their emotional impact. How much sound is written into her scripts?

PD: As time has gone on, more and more detail of the sound design is incorporated into the scripts. On Kevin, for instance many of the concepts for the sound track were written into the script. And for one of her next projects the treatment I’ve seen contains a lot of detail not only of the sound design concepts and style but also the proposed music to be used with links to the audio.

DS: There’s a lot of texture to the soundscapes of Lynne Ramsay’s movies. Is this something you’re particularly aiming for – do you approach the foley and backgrounds in special ways?

PD: Yes, I love sound editing backgrounds, or atmospheres as we call them in the UK, in fact it’s my favourite part of the sound design. I know that because of the way that Lynne approaches music that often we will not be using score to underpin or drive forward the drama, and so that the atmospheres that are chosen will have to do this job instead of emotionally underpinning the drama. I’m thinking of the death of the young boy in the canal in the opening of Ratcatcher , I always knew there would be no score there, so chose sounds that would be expressive and reflect the drama on screen, but would also belong in the onscreen environment, so consequently I chose distant factory sounds and metallic rail squeals, and orchestrated them with the unfolding of the action in the scene.

As for foley, right from the early days we have always pushed the foley tracks just that bit higher in the mix, than one might normally expect them to be. This has the effect of often isolating the character in the sonic landscape, particularly if the backgrounds are quiet and subdued, and also

drawing the audience closer to the character, if we can hear their clothes moves etc. This technique is of course dependent on very good location sound recording, to produce a clean dialogue track, and I want to mention again the importance of the work of the sound recordist Richard Flynn who recorded the location sound for both Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar, as well as editing the dialogue tracks for both films, and whose numerous location wildtracks became a big part of the sound world of both films.

DS: I really like the way you utilize silence or near-silence in subjective ways in both Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar. How many of these decisions are made during the sound editing and how many during the mixing?

PD: At first, these were decisions taken during the mix, I’m thinking of the death of the young boy in Ratcatcher in particular. However, as time has gone on and we have grown more experienced and confident, these moments are now built into the sound edit. But, one thing we’ve learnt is that you have to be very sparing with the use of absolute silence, as it is a very powerful gesture, the moment has to really justify the withdrawal of all sound, the filmmakers are in effect saying now look closely, what I’m showing you is very profound and “significant”, it is not a technique to be used lightly. There is a very good lecture on this technique, given by the British director Mike Figgis which is featured in the School of Sound book Soundscape, where he discusses going to absolute silence in his film Leaving Las Vegas, and how he had always been told previously that it was a technique that was not allowed on film sound mixing, and when he did use it, realising that part of the reason is that it produces a very powerful film “moment” and has accordingly to be used carefully.

DS: You mentioned in the earlier interview that Ramsay is very inspired by French filmmaker Robert Bresson. Could you evaluate on that?

PD: Lynne is very much inspired by the beautiful simplicity of the visual and sonic technique of Bresson, and also in her use of non-actors, especially in her shorts and first two feature films. Her admiration is reflected in her sound aesthetic and approach of preferring for the most part simple atmospheres and one or two featured foreground sounds,

However, as time has moved on her soundtracks are acquiring a more multi-layered approach whilst still preserving an affinity with her original inspiration. For me, as I’ve mentioned before, Bresson is a filmmaker I more respect than love, finding his films a little too stark for my tastes,

Having said that I feel that A Man Escaped is one of the best sound films ever made and should be studied by every film student for the rigour and precision in its use of sound and music, this film was also one of the references mentioned to me by Steve McQueen as we started work on the sound post for Hunger.

DS: I found an interview with Lynne where she’s quoted for the following: “When I go to the cinema, I want to have a cinematic experience. Some people ignore the sound and you end up seeing something you might see on television and it doesn’t explore the form. Sound is the other picture. When you show people a rough cut without the sound mix they are often really surprised. Sound creates a completely new world. With dialogue, people say a lot of things they don’t mean. I like dialogue when it’s used in a way when the body language says the complete opposite. But I love great dialogue… I think expositional dialogue is quite crass and not like real life.” Are these standpoints something you’ve been discussing?

PD: Yes, all the time, for Lynne even though she has such a strong visual background, for her sound is half the movie, a lot of directors pay lip service to this ideal, but for her it is really true. In Lynne’s films sound brings the pictures alive and is able to offer that entrance to an interior world of the subconscious and emotion that the visuals by themselves have difficulty in approaching. However, as the quote above implies, she dislikes the direct, overt or superficial and prefers a sound track that is lateral, oblique or a sound that on the surface maybe inappropriate, but in reality reveals something deeper and fundamental in the image and the scene, a sound that I call the “right wrong sound”, this is a non-diegetic sound that either never resolves itself or only resolves itself at a much later point in the film.

An example of the first would be in a film I didn’t work on, the use of a handcart sound in Lynne’s short film Gasman by Lucia Zucchetti, as the family walk along the rail tracks, the source of the sound is never seen and makes no literal sense, but story-wise makes emotional sense, another example would be the use of the garden sprinkler sound in Lynne’s new film We Need to Talk About Kevin, this sound does occur at the beginning of the film, and is used at various times in the film but only resolves itself near the very end of the film at the emotional climax, where one realises with horror the awful significance of this every day and otherwise unremarkable sound.

[…] intricate look is augmented by a rich audio design by Paul Davies, which brilliantly accentuates key sounds such as Kevin’s collicky screams against a […]