We’re starting off September’s special with an exclusive interview with our guest Paul Davies, discussing inspirations, creative methods, techniques, and how an inappropriate sound can sometimes come in handy.

Designing Sound: How did you get started in sound design? What’s been the evolution of your career?

Paul Davies: My early interest was in electronic and experimental music, in particular people like Brian Eno, Cabaret Voltaire and contemporary composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage, Terry Riley and Philip Glass. I set up a small 8 track studio with a friend, who was a sound artist, in the mid ‘80s, partly to produce our own work but also to record other bands and musicians around Cardiff, South Wales, where I lived at the time. I became involved with location sound recording for very low budget films by local filmmakers, and I also composed some music for these films as well.

With this material I applied for the sound course at the National Film and Television School which is based in Beaconsfield just outside London. For most of my time there I was mainly interested in location sound recording and re-recording mixing. It was only when the School obtained their first hard disk sound editing system, an 8 track AMS Neve Audiofile that I became more interested in the creative possibilities of sound editing, as I realised that with this technology I could start working with sound for film in a similar way to my work in electronic music. After graduation I worked for a time as a freelance sound recordist, sound editor and re-recording mixer on a variety of projects, factual TV, short films, corporate productions and low budget film.

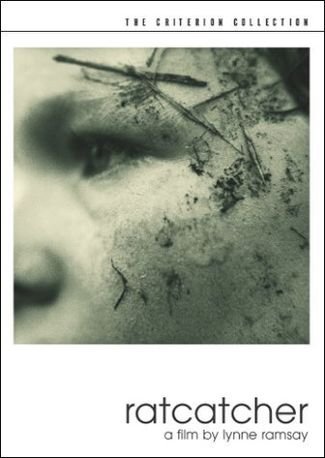

Then in one of the most important developments in my career I joined the staff of a well-established family run London sound post company Videosonics, as sound editor. The owner Dennis Weinreich, showed in a great deal of faith by employing me, despite my limited CV at that time, he obviously saw something in me that could be developed in the future. At that time Videosonics was starting to branch out from sound post for TV productions in to feature film sound and Dennis had made a significant investment in building a THX accredited re-recording stage based around an AMS Neve digital console. Because of being in the right place at the right time I was given the opportunity to work on a large number of feature film projects as sound designer and supervising sound editor, including films such as Love is the Devil by John Maybury, Ratcatcher by Lynne Ramsay and The Filth and the Fury by Julien Temple. I became freelance in 2000 and worked with Lynne Ramsay on her next film Morvern Callar as well as sound designing the horror film The Hole.

I then set up a small independent sound editing company PDSoundDesign a couple of years later, which I ran for several years with premises in the West End of London and employed a number of people who have now gone on to become established sound editors in their own right, such as Jack Gillies, Antonia Bates, Anna Bertmark and Peter Shaw. During that time we worked on films such as The Jacket, The Merchant of Venice, The Proposition, Kinky Boots, The Queen, Hunger and The American.

I am currently setting up a sound design, supervision and mixing company called The Project, with an old colleague from my Videosonics days, the re-recording mixer and sound supervisor Andrew Stirk, who has worked with the likes of Shane Meadows, Pawel Pawlikowski and Paul W.S. Anderson. This year I have completed work as sound designer on my third Lynne Ramsay feature We Need to Talk about Kevin, and I have also been developing my career in film sound education with my appointment as external assessor of the sound course at the National Film and Television School in the U.K.

In another recent development and a return to my roots I’ve recently contributed additional music cues to two films I’ve recently worked on The American and We Need to Talk about Kevin, the material I’ve contributed might best be described as “ambient music/sound design”. I’m not intending to set myself up as a film composer as such, but I think there is an increasing requirement for elements in the soundtrack that fall between the gaps of sound design and music, that are tonal and atmospheric but also seem to convey some emotion and are distinct from the atmospheres and backgrounds that might conventionally be cut.

DS: Has working in the UK influenced the way you think about sound and film industry in general?

PD: We have a strong social realist tradition in the UK, which puts the emphasis on good location recording and good dialogue mixing with little apparent room for an expressionistic use of sound. However, I’ve discovered along the way and learnt from others that in even the most apparently naturalistic drama or rigorously observational documentary there is room for sound that subtly enhances the drama and narrative. The first significant film I worked on that I felt my contribution as a sound designer was crucial was a film about the British painter Francis Bacon called Love is the Devil, written and directed by John Maybury who came from a video art background and had been a collaborator of Derek Jarman, this film came out of another British strand that of highly visual art films as best exemplified by Jarman himself and Peter Greenway. I was able to create a highly stylised soundtrack for this film and one which was in tune with my personal tastes.

Working with Lynne Ramsay on Ratcatcher, however forced me to revaluate my work, one of Lynne’s major influences is the work of Robert Bresson and her instinct is for a simple, spare soundtrack (on the surface at least), as opposed to the multi-layered complex soundtrack I favoured and had employed on Love is the Devil. Ratcatcher is a film that at first appears to be in the British social realist tradition, however I soon discovered that underneath this was not quite the case and that its soundtrack could in reality be stylised albeit in a more subtle way then in the way I had worked previously. I must also acknowledge the work of Lucia Zucchetti, the picture editor on Ratcatcher and Lynne’s previous short films, her use of atmosphere and subtle use of sound effects in her cutting copy were useful indicators and clues about the direction I should head in with the soundtrack.

DS: What are your biggest influences inside and outside the world of sound?

PD: My biggest influence in film sound was the work of Alan Splet and David Lynch, with Eraserhead in particularly being a fundamental and profound influence. It was with this film that I realised that what I thought were two mutually exclusive worlds that of sound art and experimental music and film could be combined in a new and very exciting way. I was also influenced as were many sound designers by Apocalypse Now and the way that the sound in that film conveyed such a powerful, expressionistic and elemental energy.

Two filmmakers that had an early influence on me and made me realise that film could be an art form as well as an entertainment, were Nick Roeg and Werner Herzog. I think that Nick Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to earth was the first time I had left a cinema although a little baffled and bemused by what I had seen, I was unable to get the film out of my head and found myself thinking about it for days afterwards. I also admired the dreamlike atmosphere of Herzog’s films and liked his atmospheric use of the music of the German group Popul Vuh in his soundtracks. One other very important formative influence was a book written by the composer Michael Nyman “Experimental Music, Cage and Beyond”, exploring the work of John Cage, Gavin Bryars, Steve Reich and others which I had borrowed on a whim form the local library. Reading this book led me to the realisation that music could consist of sound as well as just musical notes and that “organised sound” could be an art form in its own right, and that the bedroom experiments I’d been carrying out using a cassette recorder, an old ¼” tape machine, electric guitar and amp maybe had some validity after all.

DS: What do you love most about sound design?

PD: That it is invisible, so self-effacing and often taken for granted, but that it is also so subtle yet powerful and fundamental in its effect on the image. How meaning can be changed by different sound choices and how there is always something more to learn and improve on.

DS: How has the evolution been for you as an artist of sound? How is the balance between your craft and art in your career?

PD: Film sound is a craft, indeed there are people working in the industry (perhaps a giveaway term), who regard it as no more than that, and that it is pretentious to think otherwise. However like photography it is a craft that can also become an applied art and also a fine art, and often all three at the same time. What is unique about the craft of the sound designer is that although our work is often “invisible”, and we ourselves are often self-effacing, and reluctant to term ourselves artists, it is at its best when it is closely embedded with the image on the screen, then it is an art. But, also equally there is much to enjoy about the craft of sound editing, cutting foley/sound effects in perfect sync, taking ADR sessions and working with actors, solving technical problems and planning tracklay and mix schedules, all these can have their pleasures, though at the time in the midst of things it may often not seem that way.

DS: How do you deal with writer’s block? What kind of methods you have for getting ideas?

PD: When stuck, whether for what sort of specific sound effect or how to approach a scene or even an entire film, then I find a useful motto is “do something stupid”, by that I mean put an apparently unsuitable and inappropriate sound against the scene, and see what effect it has combined with the picture. It will probably not work, but will often by its presence provide a clue about what you should really be doing. On a more practical level, the best advice I was given when starting out was: “don’t get bogged down, keep moving on”, working in this way by just tracklaying, often when you go back to revise the tracks, you find that what you had cut is not so bad after all and provides a good basis to improve on, and I’ve always found it easier to revise, rather than looking at a blank set of tracks.

DS: You’ve been working in a lot of different formats – both fiction and documentary, both features and tv. Which things do you find interesting on each of those? Any favorite and why?

PD: Variety in my work has always been important for me, it has been good for example to move from my last film with Lynne Ramsay “We Need To Talk About Kevin”, onto a family fantasy drama “Neverland” and then to my current film a Luc Besson produced Sci-Fi action film “Lockout”.

Although what might be termed “art-house” or “independent” cinema is my natural home, I do welcome the opportunity to work on more mainstream or genre projects. In the UK we have a strong television drama tradition, and most Sound Editors and designers work or have worked in both TV and Feature film. A background in television drama, encourages discipline, pragmatism and the realisation of the importance of hitting deadlines. Directors expectations, in TV drama are mostly no different from those of their feature colleagues, it’s just that the schedules are a lot tighter in TV.

I’ve worked on two very different feature documentaries, “The Filth and The Fury” about the Sex Pistols, and “Crimson Wing” a natural history film about flamingos in East Africa for Disney Nature. Both were extremely enjoyable to work on, and it is a regret of mine that I haven’t had the chance to work on more documentaries. It’s an even bigger regret that I haven’t had the opportunity to work on any animation in my professional career, as this was something I had enjoyed at the NFTS, which had and still has a very strong animation department.

DS: You’re quite often collaborating with the same directors over and over again. Does this mean that you’re involved early on in the proces? And how do you prefer to work with directors

PD: Not as much as I would like, this is certainly the way I work with Lynne Ramsay, and have done since Morvern Callar. With Lynne I see treatments and early drafts of scripts and discuss ideas and concepts for the soundtrack, which then influence the script. However, increasingly in the UK, the sound team is often bought in late in the day, and has little opportunity to discuss sound design requirements with the director beforehand, which I think is a matter for regret and a lost opportunity. Because, I think a film really does benefit, if sound concepts and ideas can be discussed in pre-production at least, if not earlier.

DS: Which are your favorite tools?

PD: Nuendo for sound editing and its midi capabilities, Mackie’s Tracktion for its simplicity and therefore suitability of use as a “sketchpad” and its time stretching and pitch shifting capabilities, Various Native Instrument plug ins especially Reaktor 5, for its idiosyncratic user library, and last but not least my Zoom H4n for its portability and 4 track capability, great for recording quad atmoses with its internal mics and a set of miniature DPAs.

DS: What’s your favorite films for sound?

PD: As mentioned above “Eraserhead” and “Apocalypse Now”, but also “A Man Escaped” by Bresson, “Solaris” by Tarkovsky, “Mon Oncle” by Jacques Tati, and other Lynch films such as “Dune” and “Blue Velvet” in particular were big influences.

DS: What has been your most challenging project and why?

PD: I’ve worked on a few films that have had their challenges, but usually for the wrong reasons! I think the most challenging project, but also the most rewarding I’ve worked on was We Need To Talk About Kevin. I feel this film represents a big development in Lynne Ramsay’s filmmaking style, and the soundtrack had to follow suit. This soundtrack is more obviously stylised then in her previous work , but still retains the minimalist aesthetic of her previous films. I wanted with this film to try and make the soundtrack as perfectly integrated as I possibly could with the image and narrative, and this was helped because I was able to come on board the film much earlier than is usual, and was able to work closely alongside Lynne, Joe Bini her editor, and Lynne’s husband and co-script writer Rory Kinnear.

The cutting room was based in an apartment in Islington and the atmosphere was a very family and collegiate one, far removed from being stuck in some stuffy Soho cutting room. I must also mention the very important contribution to the soundtrack of re-recording mixer Robert Farr and foley supervisor Barnaby Smyth, who were both a joy to work with and instinctively understood what Lynne was looking for in the use of sound for the film. I think we have succeeded in some small way with our aims for this film, because the imagery and narrative is so strong, the soundtrack had to live up to what was on the screen. This was my most challenging but also most rewarding project to date.

DS: What would be your advice for any sound designer out there?

PD: Always keep on developing and learning, never think that you “know it all”, as I move on in my career, I’ve come to realise how little I know and how much I’ve still to learn about what makes a truly effective soundtrack that exists symbiotically with the picture and truly enhances and serves the drama.

DS: What are you currently working on? And what’s next for Paul Davies?

PD: As I mentioned earlier I’m currently working as the Supervising Sound Editor on a Sci-Fi action film, produced by Luc Besson and directed by two Irish directors Stephen St. Leger and James Mather. We’ve just finished the sound edit where we’ve been based in Dublin, I’m happy that I’ve had the opportunity to work again with Vincent Hazard as my sound designer on this project, Vincent and I have worked on many projects together in the past most notably on “The Jacket” where we worked together on the sound design. We are going to mix the film in France and I’m looking forward to working at Digital Factory in Normandy in their huge main mixing stage.

After this, I’m happy to say I will be working on a feature documentary with Andrew Stirk and I’m also working on a new project with Lynne Ramsay. In addition in discussions with a major music company about a production music library project utilising my ambient music/sound design.

It’s allways nice to hear some European approach, really nice interview and It’s nice to see that are people with working points and experiences in common.

Best,

Pedro.

wonderful musical influences and a fellow reaktor fan. NICE!!

Love the music influences !!

Enjoyed the more European approach.

Pushing the boundaries and keeping the standards high.

Thinking out of the box and use of software was an interesting angle.

Great article .