[Behind the Art is a special section of Designing Sound created with the goal of studying the artistic and creative aspects of sound design, featuring several interviews dedicated to explore the minds and creative approaches of professional sound designers from all sides of the world, with the goal of expand our creative worlds and learn what others do in order to tell great stories with sound.]

Many of you may know Tim Prebble, sound designer based on Wellington, New Zealand. Maybe you’ve heard about him by reading one of his great advices on a forum or social network; maybe you’ve been inspired because of something he shared on his fantastic blog; maybe you know him for his great sound effects libraries, or his music/netlabel, and, of course for any of the +30 films that he has been part of, as sound recordist, editor and/or designer. As his website (and that great Beatles song) states: he is “here , there and everywhere”.

This interview is something that I always wanted to do. It’s not as easy to ask a limited number of questions to someone who has influenced and inspired me (and many of you, I guess) in the way Tim has done. His philosophy, creative methods, influences, his unique way of approach his work. Let’s discover what’s in the creative mind of Tim Prebble.

Designing Sound: Could you describe your sound design philosophy? What’s sound design for you?

Tim Prebble: I started my career as a sound editor back in the early 90s, inspired by the work of directors such as Stanley Kubrick, Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, David Lynch, Akira Kurosawa, Sergio Leone, Francis Ford-Coppolla, Andrei Tarkovsky and many others. So any form of a philosophy of sound design originates for me from the active role sound (and music) play in the context of film making. Sound design for me is film sound design – that is why I do what I do.

DS: How has this philosophy and approach to your work changed through the evolution of your career?

TP: Experience is a great teacher; over time it helps develop your instincts but it is equally important to retain an open mind & to find interpretations and solutions uniquely suited to each project. I think any creative vocation is inevitably influenced by your personal life and your experiences, so the older you get the more there is to draw from. Some aspects (passion, enthusiasm, commitment, desire to experiment & explore) are as strong now as ever, whereas others (clarity of vision, personal aesthetics) are constantly evolving and developing… In the very early days I was necessarily focused on HOW things are done, but it is so important to think about WHY – the motivation, intent & dramatic purpose.

DS: How do you like to start a project?

TP: Philosophically my approach has always been that budget is not the primary issue; the most essential aspect to determine is whether creatively I am the right person for the project, and vice versa. Film making requires an inordinate amount of trust & open collaboration. Writers & directors work for many, many years to get their project into production, so I am deeply respectful of that commitment & acknowledge the creative commitment they in turn expect from me. I like to start projects as early as possible, definitely before they have been shot. I often think the most valuable work that I do for a film early on, is thinking. By starting before the shoot it means I can think about the film, dream about it and collect ideas, research its themes and practicalities. And then discuss them before the shoot has ever started. So the first step for me is reading the script and meeting with the director and producer, and establishing that sense of collaboration from the outset.

DS: How much experimentation is present in your sound design process?

TP: Experimentation is a part of all creativity and there are philosophical parallels to travel: on the way from A to B many interesting things will be discovered, and some of them may well turn out to be every bit as important as arriving at the destination. Experimentation is partly a mindset, a freedom that requires you to be vulnerable & open, to delay judgement until the result has actually occurrred, and possible new contexts have been considered. It is also important to remember that doing the wrong thing can also be essential – it can provide invaluable insight into other possible approaches. While it is easier and potentially less risky to do all the experimentation early in the schedule, I think it is also important to be open to experimentation throughout the process, including the last days of the final mix, simply because the true dramatic nature of the final film does not exist until that point. Thankfully the technology we now have available when mixing enables comparative experimentation eg after the first screening of the final mix it can be a total joy to know a scene works as mixed, but to be able to put that version aside and try a totally different approach.

DS: How do you prefer to work with directors?

TP: One interesting aspect of working in post production is that we get to work with a lot of different directors, and each director has their own style, approach & priorities. But whereas I may have worked with 30 different directors in the last ten years, each of those directors has often only worked on their own films. So every film is a unique learning experience for me, establishing the directors main focus and which elements are subjective & will require the most evolution. I thoroughly enjoy providing temp sounds early in the process eg even during the first picture assembly. The sooner the director and picture editor are hearing material from us, the more they will include sound in their decision making. Early on I am often providing temp sounds before we have even spotted the film with the director, so I have no choice but to follow my instincts and I think that can be valuable i.e. for the director to hear an interpretation that is based on reaction to the image prior to any discussion about intent. This should be self evident but its also important to constantly remind yourself that directors like to direct, so establishing a process where they are constantly hearing work in progress and providing input is important, whether its in the Avid or during screenings in my studio or via temp mixes.

DS: How powerful do you think deadlines are for our minds/creativity?

TP: I have learned to love deadlines and to appreciate how important they are in terms of decision making. Deadlines provide a clarity of vision that may not otherwise be achievable, whether they are self imposed short term deadlines, or your final pass before predubs, or literally the final mix screening before print master. Accordingly I believe that attending predubs and the final mix is essential in the development of being a sound editor. There is a vast difference between getting a note for a fix from a supervisor, and being on the dub stage and seeing for yourself why some element is not working and needs attention. All of these observations inform how you might approach a similar situation in the future and it is very important experience to gain, because these are the most important decisions – they directly affect the final film.

DS: Do you have any methods or habits that help you getting and organizing ideas? How do you deal with writer’s block?

TP: Ideas can be fleeting so it is important to capture them when they occur – never, ever say to yourself “its ok I’ll remember it….” because ideas can be mercurial and may only exist due to the state of your mind at the time. Wait an hour or a day and that idea may be gone, forever. My favourite means of collecting & evolving ideas is via the humble Moleskin notebook. It doesn’t require batteries or wifi and its small enough to always have with you, wherever you are. I’m starting to sound like a luddite but pen and paper really work for me too.

When online I heavily rely on RSS, Google Alerts and Evernote (directly and via email forwarding) to find and collect ideas. I use VoodooPad, Scrivener and DevonThink to collate & organise them, maintaing sync between all my devices via Dropbox. When working to picture I tend to rely heavily on ProTools markers, both for listing and as a non-linear sync grid. They are easy to conform as picture cuts occur but AVID really need to develop markers into a proper relational database structure with import, export and tagging/metadata. Markers are so useful it is ludicrous that their functionality is so primitive – if you agree please vote for it on IdeaScale.

With regards to writer’s block I think it is important to be able to observe yourself & your moods and pursue the aspects of your work that is most likely to achieve the best result. If you feel inspired its important to acknowledge it & to be able to pursue ideas without distraction – you don’t want to waste that energy by doing admin or a painstaking conform. Whereas if you are simply not in the mood to pursue a particularly creatively demanding aspect then there are usually other tasks that can still make productive use of your time. I rarely suffer from writers block but I’ve always found a walk or a game of table tennis is enough to both rest & oxygenate my conscious & subconscious brain.

DS: I see on your blog that you’re constantly influenced by lots of disciplines and cultures. From sound art, to experimental short films, to Japanese culture. How do these and other fields affect the way you think about sound?

TP: As humans I believe we are the sum of our experiences, so I think it is vitally important to actively seek out inspiration. A simple example of fields interacting: mixing could be considered a reductive process, effectively you begin with every relevant sound imaginable as the source material and the options are carefully reduced through collective decisions as to what is considered the best dramatic form sound can contribute to the film. I am not a mixer but I attend every film mix I work on and so reduction as a general creative process is very interesting & relevant to me – both philosophically & directly. It therefore seems logical to me to study and appreciate reductive processes in many different mediums: minimalist architecture, music, photography, poetry. The following example might seem like a tenuous connection but for me it isn’t: the vivid memory of my first experience visiting a beautiful minimalist Tadao Ando gallery on Naoshima, Japan has had a direct influence on how I have approached the sound design for a number of scenes in films many years later, both literally and metaphorically. A great work of art alters your perception – changes how you think or see or hear the world. Whether its a Zen temple in Kyoto, an art gallery in Kanazawa, Naoshima, Berlin, Barcelona, London, New York or in your home town is less important than the experiential act itself. I really believe in the idea of putting yourself in the path of interesting experiences. Travel is deeply influential to me – it is such a privilege to be able to engage with another culture. It also teaches you many things about yourself and your own culture and environment which are often taken for granted. If english is your first language, I think it is invaluable to spend time in non-english speaking countries so that you truly appreciate the role language plays, in life and in art/film.

There is a saying by the poet Matsuo Basho that I refer back to often: “Seek not to follow in the footsteps of men of old; seek what they sought.” I am deeply inspired by the work of many film makers (writers, directors, picture editors, composers, sound designers, mixers) as well as artists & musicians, but I seek to be inspired by them, not to imitate them. I think it’s important to forge your own path & develop your own approach and aesthetic to your work, so it is personal to you. When its all said & done that is the most important contribution you can make as a creative human being.

DS: You’re also a musician, how does your work as a sound designer affect the way you make music and vice versa?

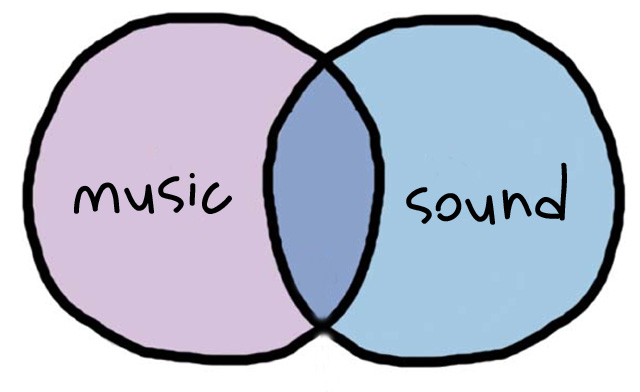

TP: It is the name of my blog but it is also a fundamental part of the way I hear the world i.e. the music of sound. Music is something I have always been passionate about, but I am as often fascinated with timbre and texture as I am by melody and rhythm. As a sound designer it is a great joy (& an amazing learning experience) collaborating with film composers; seeing their approach, process and the contribution music makes, especially when you consider that every film is an emotional world unto itself. But I’ve always been very interested in the area where music and sound overlap, regardless of whether that overlap is literal, physical or emotional. This year I am crossing a personal boundary for the first time by contributing to both the sound design and the score for a film and although I’m still two months away from officially starting, it is already a deeply fascinating process.

DS: How has living in New Zealand changed your approach to sound? Does Wellington gives you anything special in terms of creativity, vision, etc?

TP: I grew up on a farm in the South Island of New Zealand so I have always appreciated quiet. Living in a small island nation also means that you inherently have respect and awe for the ocean and the many moods of nature. Aldous Huxley once said “My father considered a walk among the mountains as the equivalent of church going” and I can relate to that philosophically.

One sound that Wellington contributes rather literally is wind, and lots of it. I read of people discussing “heavy” 70kmph winds but we regularly experience winds with gusts peaking over 140kmph! The strongest on record was 248kmph but that was back in 1959, a little before my time. It doesn’t take a huge leap of logic to appreciate that all the local sound editors have epic libraries of wind recordings. One house I lived in on the south coast was a great example; whenever there was a strong northerly wind you could open the doors on one side of the house and then perform & shape wind drafts by manipulating the wind exiting through the front door. The many forms & voices as well as the sheer power of wind are fascinating – there are wind turbines in Wellington that they regularly have to disengage due to the wind being too strong!

In terms of film, we are truly blessed to have Peter Jacksons film post facility Park Road Post here in Wellington. The fact that nearly every film director in New Zealand gets to work at Park Road Post, and on the same dub stage that films of such vast scale as LOTR were mixed, has a huge influence on the finished films and on everyone involved.

DS: Your presence on the web is very active. From your great shares on Twitter and forums, to your great blog and the fantastic idea of HISSandaROAR, where you have inspired a large group of recordist to make the first crowdsource library ever. How does this community affect you in your life as sound designer?

TP: Engaging online is really a form of collaboration, which is a natural and vital part of film making, although as with mass mediums you have to learn to filter the noise from the signal. New Zealand is about as far away from everywhere else as you can get & the internet really helps to remove the tyranny of distance. It also helps overcome some issues of living in a young, small country – I can happily ignore the fact that sport is the predominant entertainment (and religion!) in New Zealand and engage with creative people and ideas online which are more interesting to me. But what intrigues me the most about the internet as a medium, is the future and where it is headed. I figure you have to actively engage with it to try & understand it, and to appreciate the opportunities it represents.

DS: In 2009 you started a project of virtual mentorship, where -during one year- you were the mentor of several sound guys from different sides of the world. I personally know about the testimonial of one of those guys, who told me that the experience was incredible. Now, how constructive was it for you? Why did you decide to share your wisdom in this personalized way?

TP: I deeply appreciate the support I got at many crucial stages in my development as a sound editor, so my motive for offering the virtual internship was altruistic; to give something back to the equivalent of my younger self. Choosing an intern was very difficult (which is why I ended up with four interns instead of one) as every person who applied deserved my support. Through necessity I had some unspoken selection rules, for example I asked each applicant to list five of their favorite films and another five film favorites for sound. And before I read a single application I decided to eliminate anyone who listed 100% Hollywood films. I was not being anti-Hollywood in this act, I was simply being pro global film culture and for good reason: if I was auditioning chefs for an intern role and someone said they only ate food from one culture I would be deeply concerned about their world view. This is of course also fueled by my own experience; the best films I saw last year were French (MicMacs) Thai (Uncle Boonme who can recall his past lives) & Korean (Mother). So I was also culturally interested in where each of the interns was coming from, an aspect that was easier to explore remotely than locally. The only downside to the virtual internship was the time involved, which is why I haven’t as yet repeated the process and it is going to be another six months before I can even consider it again.

DS: Finally, what would be your advice to any sound designer who wants to find/enhance his artistic vision and personal creative approach?

TP: It is difficult to offer anything other than very generalised advice because each person must pursue their own ideas and find the role that best suits them – I don’t want to offer prescriptive advice for something so personal. But some practical advice? What happens in front of the mic often has more bearing on the final sound than what plugins or processing you apply, so no matter what stage you are at, a very important asset to be constantly creating is your own personal sound library. Sounds you record yourself become an important part of your resources, and are part of what makes you and your contribution unique. Especially if you’re early in your career, think and plan long term, but as a part of your constant work ethic recording for your sound library is some of the best potential use of your time. There is a whole world of sound out there, go forth and experience it… and take a recorder with you!

One of the most insightful interviews I have ever read.

Once again great words and insight from a great guy! His generosity speaks of himself as a person and that reflects in the results of his work! Thanks again for another great interview!

Great Interview! Many thanks to both Miguel and Tim.

Excellent interview, thanks to both of you for doing it.

“… the area where music and sound overlap, regardless of whether that overlap is literal, physical or emotional.” Great stuff!

Great interview……… Tim is the Davinci of Field Recording…… great job Miguel!!!

Great!!!!……… Tim is the Davinci of Field Recording…… great job Miguel!!!

Wonderful interview. Thank you very much Miguel and Tim. You are both a constant inspiration to me.

Once more, delightful material. Great balance between practicality and depth. Thanks to Tim and Miguel for inspiring us to ‘seek the paths of sound giants’.

Very interesting and inspiring interview! Just being curious, which microphone stands do you use in your last picture? I am looking for really light ones and I can’t find them in our local stores :)

Cheers, david

As a student i found it very insightful. It is clear in his language that he is wise within his field. Thank you for the interview

@David Phillipp

Manfronto as per this post:

http://www.noisejockey.net/blog/2009/07/07/lightweight-mic-stands-in-the-field/

an interview which was worthy reading…likes to work with him…:)

Just discovered this gem, deserves a re-posting! Great insights and outlook.