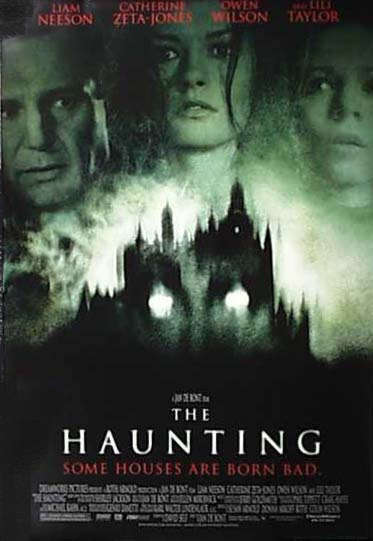

The Hauting, a horror movie directed by Jan de Bont. The Sound Design by Gary Rydstrom, wich had a interesting interview at filmsound.org talking about the sound of The Haunting. Let’s see:

On a recording soundstage here at George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch, the movie’s sound designer, Gary Rydstrom, had just received an urgent call from a colleague. An image of the movie’s fragile heroine, played by Lili Taylor, was frozen on a movie screen and on two video monitors. Rydstrom and his two assistants looked almost as tense as the actress, who was cowering in bed, her eyes fixed on something on the ornately carved ceiling.

“That’s where the visual effect goes,’ said Rydstrom, advancing the film a few frames. “They’ve just added something new to it, so we have to come up with an additional sound effect.” Though the art of sound is often viewed as the last and hastiest element of movie production, Rydstrom has had two months to prepare, an unusually long time. For a suspense film about largely unseen forces, evocative sound is essential to the movie’s success.

“We had to find a way to give the house a voice, even before we began shooting,” said De Bont. “Normally, actors would be reacting to the director, who’s saying things like: ‘Now you hear a footstep! Now you hear a door creaking!’ And that’s horrible for them. They don’t know where the sound is coming from, where it’s going, or what it will eventually sound like in the movie. But if you can fix it for them there on the set, you get fantastic reactions.”

Soon after “The Haunting” was green-lighted by Dreamworks, De Bont took steps to insure that its actors (including Liam Neeson and Catherine Zeta-Jones) could react not merely to one another but to an invisible cast of thousands. His first choice for the job was Rydstrom, 40, who has shared seven Academy Awards for sound design and sound effects editing, most recently for “Saving Private Ryan.” Rydstrom’s resume is diverse. It includes “Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace,” “Titanic,” “The Horse Whisperer,” “Jurassic Park” and “Terminator 2: Judgement Day.” But he had done the sound for only one ghost movie, and that was the G-rated “Casper.”

” ‘Casper’ was a friendly ghost; this was going to be different,” Rydstrom said. “To me, a scary sound is one that you can’t pin down, or one that is behind you. Something we use a lot is the sense of space, the ghostly movements. The sounds spin around the room in a strange way. The movie is full of atmosphere and ambiences that have little whispery sounds. You’re always becoming attuned to these things that might be a distant voice in the wind.”

Inspired by the script and by preliminary drawings by the film’s production designer, Eugenio Zanetti, Rydstrom recorded — and then distorted — the sounds that would emanate from a place that Jackson called “a masterpiece of architectural misdirection.” (Exteriors were filmed at Harlaxton Manor near Lincolnshire, England, a Gothic-Jacobean-Baroque building; interiors were built near Los Angeles.

To insure a fresh approach, Rydstrom and his associates searched for new variations on the sounds that audiences associate with haunted houses. After that, he said, the biggest challenge was to come up with names for each sample. (The results, indexed on a computer, sound like a record company roster: Buzzmoan-ambience, Rumble-wave, Demon speed-by, Dreaded-booms, Thunder-switch.)

The team’s one concession to movie tradition, he said, was to record a magnificently creaky door that he found in the cellar of a Northern California winery. He also happened to have extensive recordings made inside an old hotel near Glacier National Park in Montana, where Rydstrom and his wife were stranded during a June snowstorm several years ago. “I spent three days recording gusting winds through the cracks of windows and doors, so that came in handy,” he said. “It sounds as though the wind has a child’s voice inside it — a little screaming, whispering human being in it.”

The first sound the audience will hear upon entering Hill House, however, is a slow, booming, rhythmic breathing. “When the front door opens for the first time, there’s also a sort of exhalation, an airy sound that takes you into the house,” Rydstrom said. To capture that sound, he set up a digital recorder in his Saab Turbo and risked becoming a ghost himself. “If you drive about 80 miles an hour on the freeway and open your sunroof, you get a great ‘bwaaa!’ sound,” he said. “It was dangerous, so I did it late at night so there was no one around to hit.”

But it was the booming sounds, not the breathing, that proved to be most impressive. During the filming, De Bont operated a digital audio player and used about 100 of Rydstrom’s sounds to inspire and surprise the actors. Ms. Taylor said that the sound cues had provided an integral part of her performance. “Shrill screaming, strange wild banging, children calling me lightly — all sorts of noises,” she said. “One time in England, when Jan didn’t have the sound machine, he started making sounds with pots and pans for us. I loved that.”

The most unnerving sound effects, Ms. Taylor said, were those that suggest a huge, unseen presence moving overhead. “It was low, reverberating, eerie sound,” she said, “like a giant sliding its feet, with a little noise in between the slides.”

The dragging sound, Rydstrom said, was derived from a recording of a 19th-century iron lung that he found in a San Francisco museum. “We slowed down the mechanical sound, and it turned into a rhythmic sweep-clunk, sweep-clunk,” he said. The sounds of rapping, booms and crashes came from some energetic recording sessions at several Bay Area houses, all abandoned and set for demolition. “We went in there with baseball bats and smashed the hell out of walls and doors,” he said. “But for the final mix, we almost always ended up using a sweetener of some distant explosion or artillery sound.”

Despite the pyrotechnics, Rydstrom believes that “sound is all about emotion, the way music is emotion.” “We don’t quite understand why rhythm and pitch and frequency stir us emotionally, but they do,” he said. “It would be hard to write a textbook and say: With a certain pitch or frequency, you will get a certain reaction in the listener. So a lot of sound work is to take a guess and continually gauge your own reaction.

“One of the great compliments I’ve ever heard was from a man who told me that his son loved to watch ‘Jurassic Park,’ but he was too frightened so he’d turn the sound off and watch. Without the sound, it was no longer scary to him, but he still loved it. It was good to know that that’s where the scariness came from.”