Pure sound design, or the idea of designing without visuals or reference, is a unique experience facing many designers both professionally and personally. Sometimes we take on the challenge of pure sound design because we feel it will better ourselves or the pipelines that we create. Other times, it is sprung upon us, forcing us to react and adapt. To learn more about how pure sound design can function in our daily professional lives, I decided to catch up with Kevin Dusablon (Audio Director at Pullstring, Inc, formerly Toytalk), and Mike Forst (Audio Experience Designer).

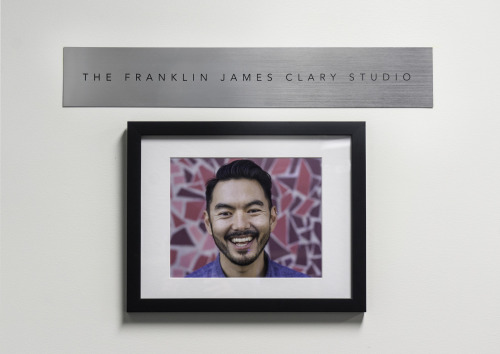

In talking with Kevin and Mike, I learned how integrale pure sound design is to their development process at Pullstring, a process that was advocated for and created by Franklin Clary. Even though he is no longer with us today, it was through Frank’s vision and creative passion that Pullstring was able to adopt a pipeline that used pure sound design for everything from audio concept design and custom material building to storytelling and user experience. “He went out of his way to set that up at Pullstring,” says Kevin. “It didn’t feel like that was the way the show would have went without Frank taking the initiative to do that. Often at Pullstring, we’d get together and the Director would say, ‘Okay there’s this thing, a big, heavy monster holding maybe something like club, set in a Roman era by the ocean.’ And Frank would often say at that point, ‘Okay, we know what the directors want even if we don’t have any visuals yet.’”

In this creative space, Frank, Kevin, and Mike, were acting as more than just content creators; they were executing a vision on a high level. “There are probably a lot of sound designers out there who feel like the term ‘sound designer’ has been watered down,” says Kevin. “Today, people sometimes think a sound designer is a guy who makes tire squeals. No. A sound designer gets on the show early and is thinking about the audio experience of the product. Period. And that is sound designing to black. That’s them thinking without any sketches, having exciting conversations with the director or writer, thinking about what inspires them, and then formulating the sounds they want to do. In their mind, they’re making the design concepts.”

Once they had a chance to sync up with the director and talk about their vision, Frank would send off Kevin (with Kevin later sending off Mike) to capture raw recordings that would eventually be edited into the audio that became concepts and later custom library material. “Frank would say, ‘These are the things that I think I’m going to need: I need you to go out and find alarms, booms, heavy ratchets, creaking wood, and quiet wilderness wind,” says Kevin. “And I would have to go away, find examples in media, think really hard about who I can call and where I can drive to. [perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”In a way, I’m designing to black as a field recordist, because I’m designing in my mind before I spend all the time and energy it would take to go lay those sounds down.” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””][/perfectpullquote] In a way, I’m designing to black as a field recordist, because I’m designing in my mind before I spend all the time and energy it would take to go lay those sounds down. I’m literally scouring the open world for sounds based on a few adjectives, a few descriptors, and a few style guides for the show way up front, way before animation or art is kicked off.”

Once these raw recordings were captured, they could be edited into concept work and sound sets, allowing for custom designed material building. “So let’s say you’re in early talks about a particular project,” says Kevin, “and you know there’s going to be spaceships, and the esthetic for the spaceships is a particular thing whether it’s futuristic or retro. You can just go start pulling raw sounds from a library, do some source recording, and just design. Just design to no picture. You can build yourself a sound set that you can reach into later.” These sound sets are often so impactful that they are the source of early feedback and inspiration. “As a sound designer, if you get the opportunity to lead the charge and set the vibe, it’s really awesome,” says Mike. “The ability to create sound sets, so that people can look at them and say, ‘I really like this one, I don’t so much like this one, but I like this one thing about that one,’ is an incredible way to hone in your design for when you do get picture. Just as much as art influences us, audio can influence art. And I personally like the idea of influencing each other, all the time.”

The creation of Pullstring’s audio pipeline wasn’t the only situation in which pure sound design was used in their development process; sometimes the limited timeline or budget called for it. “During some of my experiences at Pullstring,” says Kevin, “we were in the position where we had limited visual resource and a little more resource on the audio team. So, rather than depict large establishing shots for our interactive skits using panning or elaborate title cards, we did audio ‘establishing shots.’ We used audio to give you your place, time, and set the scene. And that was a really cool way to lead into a picture. So, for example, there would be about 10 seconds of no visual whatsoever, where we would be establishing trees, birds, and wind. And we would focus on a granular feeling as if you’re looking at a tight shot. Then, you’d see the caption, saying ‘The Bird’s Nest,’ where we would drop in the bird chirping and fade up to a static shot of a bird’s nest.”

Other times, the nature of the product itself dictated the need for sound design to black. “Currently, I’m designing for hardware that is an audio only experience,” says Kevin. “In this case, it’s all black, even the UI. So how do you bring a user into this experience, make them feel as if they have control, set a tone for them, and then deliver a compelling story that is paced appropriately for the content?” “For the UI design, you’re just given a list of all these different feelings,” adds Mike. “What sounds like an error? What sounds like success? Did you turn the knob up? Did you turn the knob down? How can I explain with audio how you’re supposed to feel?”

[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been on the phone and via email back and forth with younger companies, especially game companies, discussing with them that I absolutely have to see something.” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””][/perfectpullquote] At the end of the day, a series of words scribbled onto a napkin, custom recordings, and uniquely designed-to-black sounds isn’t how you’re going to finish your film or product. Because at the end of the day, you’re still going to have to cut to picture. “Sometimes it’s difficult to design first,” says Mike. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been on the phone and via email back and forth with younger companies, especially game companies, discussing with them that I absolutely have to see something. Because I know, that whatever team I’m working on, whatever I design, I’m going to have to deliver new assets when they actually animate or get it in-game.” “You can sound design all day, you can give them all the spaceship sets they want,” adds Kevin, “But you still need to cut to picture. These effects are inspirational, they’re wonderful, they’re in my library now, but I don’t really know how things are landing. I don’t know where all the beats are visually until I see it. And it’s one of those things, where if you’ve been on a lot projects, you’ve seen lots of producers and directors, and you see them kick off both teams simultaneously with the same drop dead date, you really have to have the confidence to say, ‘Hey you need to build in time at the end of your pipeline for sound.’”

But just because pure sound design isn’t the only sustainable form of audio design for film or games, doesn’t mean that it should be thrown out altogether. Sound designing to black has as real of an impact on the physical and emotional success of a product as cutting to picture. “Frank really helped me understand the idea of raw material as a rad step in the process that I never considered much,” says Kevin. [perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”Frank really helped me understand the idea of raw material as a rad step in the process that I never considered much.” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””][/perfectpullquote] “I had done other jobs and other contracting gigs before meeting Frank, but learned that if you have the time in your pipeline… if you can make the time to go and create that raw material, that’s so much fun. It’s exciting, and,” as Mike cut in, “It’s almost as efficient. If not more efficient. Not only are you not spending the time digging through libraries, but you’re also creating a library even if you failed at finding the right sound during the first couple iterations.” “We are thinking about the greater world that we’re building,” adds Kevin. “Sure we’re making this episode of this thing right now, but let’s project success out and challenge ourselves to have this world defined to a much higher concept.”

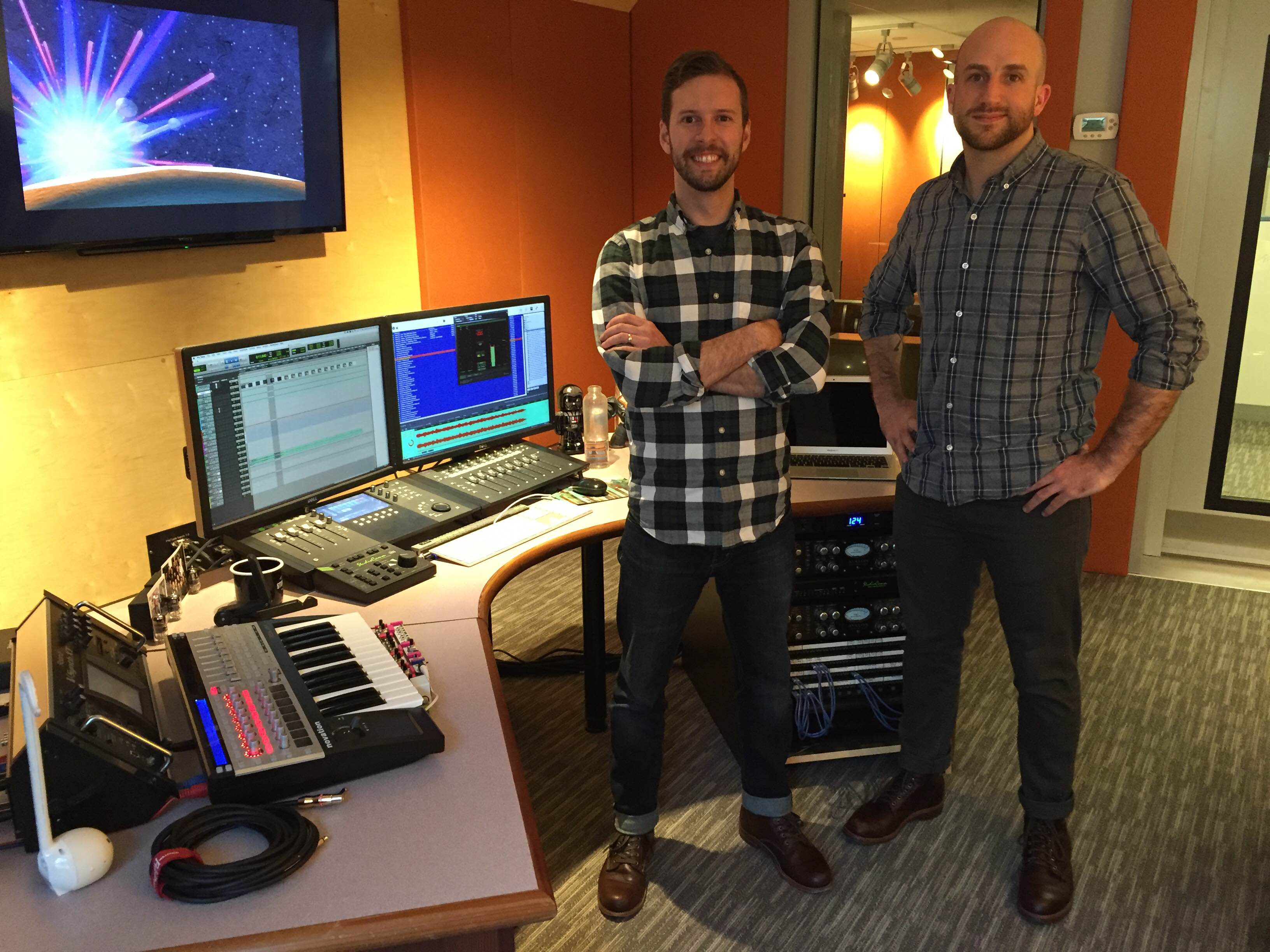

In memory of Franklin James Clary, and a big thank you to Mike Forst and Kevin Dusablon for contributing this piece.