Ira Greenberg is director of the Center of Creative Computation and is a professor at SMU. He’s had a career as a painter, animator, designer, programmer, arts director, professor and author. In addition to having lectured at universities across the world, he’s authored three books on creative coding, including the first major reference for Processing. His current research involves the development of an “idiosyncratic” 3D graphics library, titled “Protobyte“. Protobytes are algorithmically generated virtual lifeforms based on mathematic expressions.

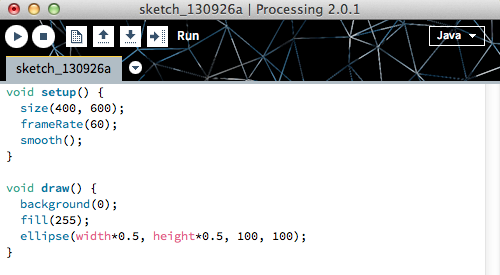

In addition to my work in sound, I have dabbled around with creative programming languages like Processing and openFrameworks. There is something quite exciting about thinking of code as a design tool. This thinking extends even beyond visual coding languages to graphical sound languages like Max/Pd to more hardcore languages like C. If an equaliser or compressor could be a creative tool, why not code at a much more granular level? This gets even more interesting when thinking of procedural sound and synthesis, where sound is designed using algorithms inspired by the real world.

Ira recently visited Edinburgh with his students and was kind enough to spend some time with me and share his thoughts for Designing Sound. There’s something magical in the overlap of design, code, creativity and logic.

DS: Ira, lets start with your background.

IG: I was trained in painting, both in undergraduate and graduate school. Previous to that I had studied sciences a little bit. I was interested in sciences but as I progressed through school I got more interested in arts and creative writing. By the time I graduated from school I decided that I pretty much wanted to be a painter. I did that for a number years — my schooling was between ‘84 and ‘92 — and towards the end of my graduate school years I got involved in computer graphics a little bit, more pragmatically to pay the bills and I got involved in some graphic design work. My interest originally was completely in studio art. As I got increasingly involved in computer graphics I was torn in two different directions because I was extremely fascinated by it, especially because of my early interest in science. For many years I did not understand how to connect the work I was doing in computer graphics to my art. That took many many years to transition, which I think it has fully at this point where my creative practice is exclusively programming. I first started out using programmes like Photoshop, Illustrator, Corel Express and that sort of thing — so I went through the history of multimedia with really old programs that don’t exist any more, through 3D modelling, animation, digital video, some sound design (but minimal sound design) then into scripting web stuff and eventually into pure programming. Now my work probably looks as close to computer science, at least superficially, as it does to what we might think as creative practice.

DS: Although your work wouldn’t really fall into computer science?

IG: That is a very good question. Some of my work does fit within certain research areas in computer science, but my intention is never explicitly to solve computer science problems. I’ve found myself overlapping that space a little, specifically in terms of teaching. My interest in teaching programming as a creative medium has naturally overlapped with pedagogy in computer science. It was a total accident and I never intended to do that. I still pretty much work as a fine artist in many ways because I don’t think so much about application or utility. It is a sort of self directed inquiry. I tend to have an aesthetic reason for what I’m doing even though the aesthetic can sort of go from output to craft issues in terms of coding.

DS: If computer science is about solving problems, to some extent, do you also see your work with design as solving problems?

IG: There is a very fuzzy space or line between ubiquitous design and more silo type of design we have in engineering. So, absolutely. I’m probably even further removed toward the lack of utility than that in many ways. It is almost pure research for me in terms of my interests, sort of self indulgent to some degree — as opposed to thinking about the impact in terms of the creative practice on others.

DS: Could you tell us more about your research?

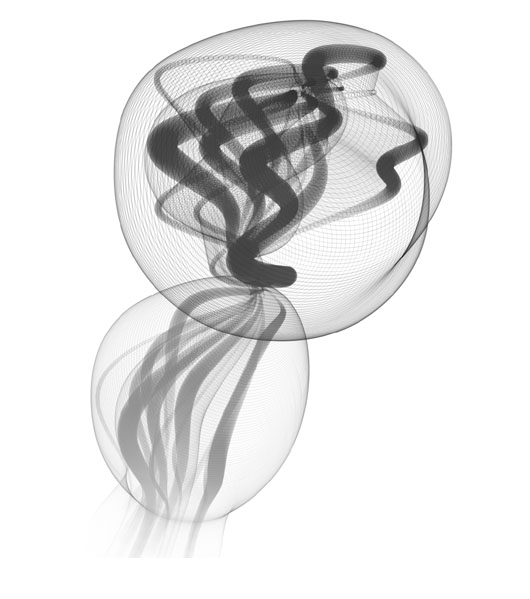

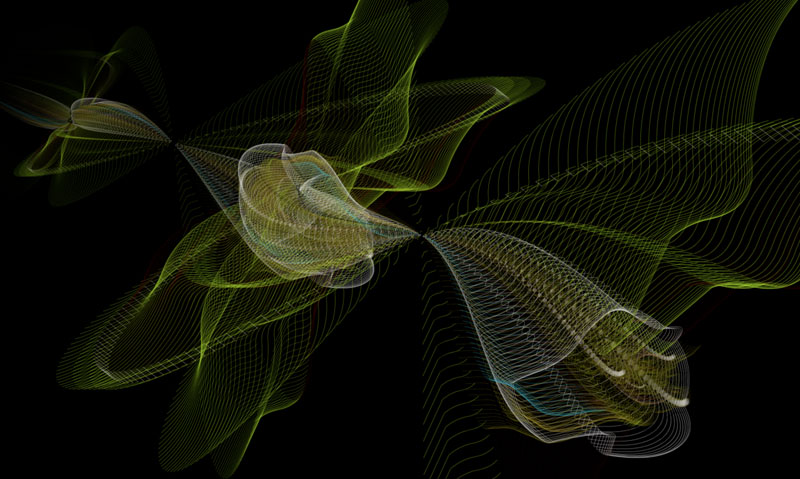

IG: I have been working on a large library system called Protobytes. As this point it is a C++ library for doing the sort of creative inquiry I’m interested in — in artificial lifeforms, aesthetically but in a very multidimensional way so that they have levels of motility, the kind of geometries in terms of their form, how they fit together and potentially issues like breeding and things like that. It is very aesthetically based and driven.

I have been writing a bunch of books in computer science pedagogy that was originally about teaching artists to code. But it has transitioned into teaching everybody how to code. Some of those principles that we used to teach creative folk seem to be working really well for more traditional computer science and engineering students.

DS: Is your work with Protobytes inspired by nature or are they completely design driven or some sort of a mix?

IG: I would say it is some sort of a mix. In many ways I am inspired by nature, but once I start building I am inspired by what falls out of the creative process. It’s very much a discovery based process for me. I tend not to think so much about why they exist or what other functionality they connect to. If I have to create a metaphor, it is more about walking through a jungle with a machete looking for civilisation and that is really what gets me most excited.

DS: Isn’t most of design like that?

IG: It can. Some designers always have a client connection or a very specific service they are trying to provide and then there’s an integration of their own vision in trying to solve a very specific problem. I’m further removed from that. I believe that at any moment I could be redirected and the problem could morph. I am not trying to solve a tangible client driven problem — everything is open to renegotiation.

DS: That does link to programmes like Processing or Max/MSP where you start with a completely blank canvas and it is really up to you to take it to where you want it to be. Does that hamper the creative process in any way?

IG: Because of the lack of limitations?

DS: Yes and being overwhelmed by possibilities.

IG: Not for me. If there is any distinction between studio practice versus applied design practice, there is a sort of map I have in my head. Even though I am forging wildly, there is still a sense of where I exist on that map, sort of the way a researcher might have a sense of what’s been going on in their field while they are looking for new territory. In some ways that imposes limitations along with my own personal limitations — there are some things that I’m better at.

DS: Is the outcome explicitly described in your head?

IG: I don’t know actually. I’m most happy when the outcome is a surprise. It was the same when I was painting. In the creative process I would do something almost as if I was watching somebody else do it. That is a little harder to get to in what I do now, maybe in a couple of generations in will be easier (laughs). At this point it is still very explicit with these very early tools or mediums or whatever you want to call it.

DS: If you have to pick out things that are similar between painting and code, what are they, if there are any?

IG: I think when both processes are going well there is a sort of a meditative flow, where intellectual, quantitative, analytical work and intuition collide in a really interesting way. They are both extremely iterative — that is another fascinating thing. I would say code is even more iterative than paint. There isn’t a single way of doing it, you can circle around and loop back and erase and put back…that is the most fundamental aspect of the medium that I’m most connected to.

DS: Or is it just easier to work with data when being inspired by science or mathematics?

IG: I don’t find it easier because I find myself constantly pushing the problem complexity. I’m always in a state where most of my stuff is failing and there are moments where they are not failing. I feel 99% of what I do are near misses. That is what is most interesting. I wish it had gotten easier but it doesn’t seem to be the case (laughs).

DS: That is reassuring. It seems to be something most designers feel — not being good enough and always looking for room to improve. Does that affect your work?

IG: I don’t know if it hampers the quality of work. I’m always focussed on processes. So if the process is flowing then I generally trust what’s coming out of the process. Even though I don’t have a clear sense of the value of the objects as I used to have when I was painting, because of the historical connection.

DS: How do you make these judgements, about your work being good enough or not?

IG: That is a good question. I’m honestly not really sure. There are certain things that I will create that will continue to seem engaging to me and I have more trust in those sort things. But at some point I might look at them and think that they are not really very good. So, I don’t know!

DS: Do you have a set workflow?

IG: I start over a lot. I have lots and lots of restarts. I tend to work all over the place. One of the nice things about code is the ability to take apart a larger system and blow it out, iterate and eventually hopefully it will fit back together…even though it often changes all the other parts around it too. That seems to be a consistent thing that I do, where I work in multiple places at one time. It is not the most efficient way to work in terms of solving a specific thing but it certainly keeps me most engaged in the process, which to me is the most important part.

http://www.iragreenberg.com/

https://twitter.com/iragreenberg