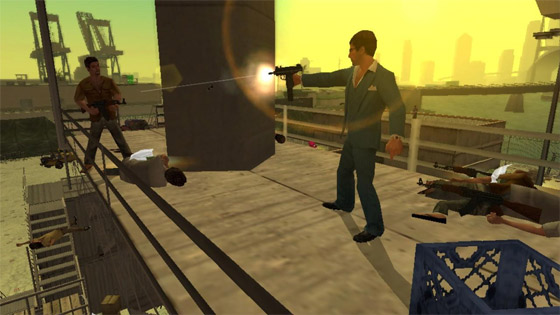

Scarface: The world is yours was one of the most important achievements in the carrer of Rob Bridgett. We already seen some information about this title, on the special of Randy Thom, who also participated in the making of the sound od Scarface (VG). In the video of the top, you can see Rob Bridgett doing a “live game mixing” demo of Scarface Sound at GDC 2007. (Note that there is some questionable language in the video)

Introduction (By Rob Bridgett for Designing Sound)

Looking back at the Scarface game’s audio production I am still astonished by its scope and ambition. For me it reflects some of the visual and auditory excess present in the Scarface movie. Looking back from the perspective of our recent economic recession it seems like a very decadent production, but it couldn’t really have been done any other way, it was true to the spirit of the movie. The audio budget itself was significantly larger than most, but this enabled us to make some very big moves in bridging the gap between movie audio production and game audio production. The question for me with regards to film sound and game sound, and it was a challenge on this project, was always (and still is) “Where can these two branches of audio production intersect usefully?”

The biggest win for the game was in getting the audio team at Skywalker involved and invested in our project, working with us on ‘movie style’ post-production sound for a game. We effectively defined what ‘movie style post-production on a game’ was. This allowed us to carefully plan in advance four whole weeks of off-site audio production, completely undistracted by our regular meetings, concentrating on only the sound of the game and how we could improve it. This all happened at the end of post-production when the changes we made made had the most impact overall.

In our preparation we spent time leveraging our in-house technology to best fit the working styles of movie sound professionals in the form of a tactile mixing desk interface for controlling in-game parameters. Best of all, having the input of a fresh and enthusiastic post-production audio team injected a totally renewed passion for the quality of the game audio into the entire sound team, who had up until that point been working on that single project for three years.

WHAT WENT RIGHT (some excerpts from Gamasutra)

Dialogue

Designing a flexible and reactive dialogue system that immersed the player was a huge challenge, and one of the core game features we had to get right. The dialogue had to be a cohesive part of the Scarface universe, so inevitably there needed to be a certain amount of fowl language and a great deal of humor.

Designer involvement with the dialogue system was needed from day one of the project and we got this support and involvement in the form of the project’s design lead, Pete Low. Design was therefore involved in script and character development for each and every character, particularly in establishing the emotional range of dialogue that would be required from Tony himself.

Each character that was designed had around 10 categories of reaction, and for each of those categories they had around 10 variants of line that could be played each time one of those events occurred. This meant that each character had around 100+ lines, not to mention all the cinematic lines and mission specific dialogue that were required. A great deal of the additional dialogue for the in-game characters was written by writers local to us in Vancouver, they essentially churned out a huge quantity of situational one-liners for hundreds of characters resulting in over 33,000.

Post Production: Sound Design and Mix at Skywalker Sound

We wanted to work with a post production sound team using a similar model to the way that movie sound is ‘post-produced’ at the end of a project. Typically in games the last month of a project is a real scramble to fix problems and to make sure everything is actually being heard; however, we wanted to bring the whole audio development environment off-site during this time so we could concentrate on quality without any of the panic and distractions that come with that crunch period at the end of the project.

Having visited several ‘Hollywood’ post production studios, the decision to work with Skywalker was pretty clear for what we needed. We knew they had done work on games before, but that isn’t what attracted us to them. They had the staff and experience we needed to really push the game in the direction of a movie. There were two things we needed to concentrate on in our post-production; the sound design and the final mix.

Post-Production Sound Design

We had an initial week of preparation work with Randy Thom in March where we sat down, reviewed the movie and went through the Scarface game running on disc, noting all the areas we felt we could improve the sounds we had in there. We came away with a lot of ambience, weapon sounds and a stack of vehicle sounds that we then spent two months implementing into the game back in Vancouver.

The second week we spent with Randy was for the real-time sound effects replacement in June, where Randy got to create sounds, have them built into the game, and then decided on what needed changing about those sounds in order for them to work how we wanted them to. We managed to iterate relatively quickly in terms of video games and both felt that this was the only way we could have worked, given that in the past, video games developers often get sound designers to create sounds without seeing the game, and certainly without being able to hear how those sounds work in context after implementation and down-sampling has occurred.

The sound effects in the game quickly began to take on the direction of the personality of Tony Montana, him being a larger than life character. A great example is Tony’s M16 in the opening mansion shootout. We worked hard on getting the enemy weapons sounding good, so good in fact that we eventually realized that Tony’s M16 now sounded less aggressive by comparison. We worked on Tony’s M16 sound for a whole day; we even gave it the largest sample rate of any sound in the game so it will cut through in that particular scene.

The Mix

In terms of the final mix, this was something we felt had never been attempted successfully in the past in video games, both from a technology point of view and from the point of view of having the whole game be mixed by someone who specializes in film mixing.

Juan Peralta, our mixer, fit the bill perfectly as he is passionate about games and has mixed a ton of movies. Also doing the mix on a sound stage with a near-field monitor set-up that has been calibrated by THX was the perfect place to mix for a home theatre system. It would have made little sense for us to use some of the bigger rooms available at Skywalker, as they are specially designed for theatrical releases.

The sound stage we were on, The Elia Kazan, is used for theatrical mixing, but the near field Genelec set up we employed is how they do DVD mixing. This made it perfect for our needs on a video game. We were pretty clear that most people now have 5.1 theatre systems in their homes, primarily for watching movies, but those with consoles are of course plugging them into these systems and expecting the same quality of sound as they get from their movie experience.

The major difference with the mix on Scarface was that we were connecting the audio levels of all the sounds in the game to a software mixing console, and then connecting that to a hardware mixing console (the Mackie Control Universal and Extender). We route every sound to various busses; for example, all non-player character dialogue goes to the ‘dialogue bus’, all Tony’s dialogue goes to the ‘Tony bus’, all bullet impacts and squibs go to the ‘squib bus’, score goes to the ‘music bus’, tape player music to the ‘tape bus’, and so on. In all we had around 20 busses. All these were mapped out in our proprietary interactive audio system called “Audio builder” developed by our Advanced Technology Group at Radical in Vancouver.

This then connects via the PC it is running on, to both the game and via MIDI to a Mackie Control and a Mackie Extender console, so all these busses appeared on the mixing board as channels. We wouldn’t have been able to mix the game in such a way without that external MIDI controller functionality – all mixing prior to this was done on-screen with a mouse clumsily moving the fader levels. It was so difficult to move the faders in that way, it felt very counter intuitive, and certainly wouldn’t have made any sense to expect a professional film mixer to use on-screen mouse driven faders. [..]

Working with THX

THX’s involvement in the project, particularly during post-production, proved to be highly valuable. The THX Games certification not only encompasses audio but also the visual environment in which the artists work. THX certification is designed to ensure game developers always work in highly standardized environments with calibrated equipment, whether that’s a PC workstation (for texture artists, etc.) or a large mixing studio, like the ones at Skywalker Sound.

The THX engineers visited Radical as we were entering our Pre Alpha stage of production and took measurements that enabled us to calibrate all the art lead’s monitors, and led to the establishment of a THX room on the game team’s floor in which any artist could drop by and check their work on calibrated equipment.

The THX Professional Applications Engineer, Andrew Poulain was on site when we set up the mix stage at Skywalker in order to ensure the room and equipment was calibrated correctly, which again proved invaluable for our mix to take place as we were making a lot of critical artistic decisions about the audio in this environment, and we had to know that what we heard was entirely accurate.

WHAT WENT WRONG

Design Changes During Production

Though unavoidable and clearly for the greater good of the game, the change of direction for the project midway through development brought about by a six month extension to our Alpha date, and presented challenges for the dialogue system and for the flexibility of the content we had already recorded.

These changes meant that many scenes that had been written for the story were cut completely, and although some scenes were re-appropriated they did not make as much coherent sense as the full scenes they used to be. Many characters were also cut from the game, as well as many side missions for which very specific characters had been created, cast and recorded. Those characters now were only to appear in the game world as pedestrians, which made them seem a little odd without their context.

With all the ripples that the extension gave us, these changes led eventually to a much more streamlined and solid product. The extension in the amount of time we had also allowed us to plan and execute the post-production mixing, and thus gave us a huge gain in terms of final audio quality.

Cinematics Production Cut Off Too Late

Production of the huge amounts of cinematics that we have in the game was eventually cut off around two weeks before we went off-site to Skywalker to mix the game’s audio. This gave us a mere two weeks to work on Foley performance, recording and editing for those scenes.

Due to the huge amount of cinematic cut-scenes in the game, we had to prioritize the more important ones to receive the attention of full Foley, as there simply was not enough time to perform Foley for all the cut scenes we had. Our internal Foley team, Scott Morgan, Cory Hawthorne and Roman Tomazin, worked for a solid week in performing the Foley, and then a further week editing and bouncing down the Foley mixes for integration into the sessions which contained SFX and dialogue.

This practically left no time to do mix-downs of the final sessions including dialogue and sound effects, so the team were put under a great deal of pressure to bounce out and mix all the cinematics for the game in both Pro Logic II encoded versions and in Dolby 5.1 six channel mixes. These were all bounced out over the course of two or three long evenings and the intention was not to touch these mixes once we got to Skywalker.

However, once arriving on the stage we found we needed to add more sounds and balance the sounds in some of the cinematics, so as we came to them we re-bounced them on the mix stage. A dedicated month for Foley and premixing the cinematics is a must for future productions of this scale.

Dialogue

Recording the amount of dialogue we did, in excess of 33,000 lines, was a huge undertaking. Recording wasn’t completed until March 2006, totaling almost a year and a half of VO casting, recording, editing and implementation.

One of the things that contributed significantly to this amount of time was the extension to the project half way through the first phase of our recording, and therefore new designs and ripples in the narrative meant new characters and new scenes, and a good amount of callback sessions were required half way through production.

Improvements to the dialogue system soon became evident when we realized the huge amount of content we had to manage. A simple, dedicated database system would need to be developed to enter, sort, organize, print, edit and debug all the dialogue. We used Microsoft Excel to manage the entire dialogue on this project, which although workable, proved very hard to manage and debug, making dialogue management a full-time job.

It also proved inflexible later on in development when we needed to re-appropriate lines of dialogue to be used in new situations, as our naming convention dictated the use of dialogue in the game to a great extent, and meant we had to duplicate and rename content in order to get it used in new places in the game. The development of a flexible system, which treats functionality independent of filename and which packages the files needed per character only at the build process, would help tremendously on similar scale projects.

Continue Reading (with conclusion, databox and more) at Gamasutra…

Videos via audiophilemonkey